What do you find most irritating about this time of year? The drawing in of dark and cold nights? The hideous adoption of that consumerist import ‘Black Friday’? People putting up Christmas trees when we have only just started Advent? Being urged to spend more money by means of schmaltzy human interest mini-dramas?

For me, it is the repeated but ill-founded claim that Jesus was born in a stable, alone and isolated, with his family ostracised by the community—despite the complete lack of evidence for this reconstruction. It will be repeated in pulpits, real and virtual, up and down the land, so I do not apologise for reposting once more this annual feature.

Besides, my reposting this article has now become part of our annual celebrations…!

Picture Jesus’ nativity. Bethlehem town sits still beneath the moonlight, totally unaware that the son of God has been born in one of its poor and lowly outbuildings. In an anonymous backstreet, tucked away out of sight, we find a draughty stable. Inside, warm with the heat of the animals, a family sits quietly. Lit by a warm glow, a donkey, cow and an ox lie serene at the side of the scene. The cow breathes out a gentle moo and the baby in the straw filled manger stirs. Kneeling close by Mary, Joseph and a small lamb sit in silent adoration of the child. All is calm, all is not quite right.

I am sorry to spoil the scene, but Jesus wasn’t born in a stable, and, curiously, the New Testament hardly even hints that this might have been the case. This might shatter the Christmas card scenes and cut out a few characters from the children’s nativity line-up, but it’s worth paying attention to.

This long-held idea demonstrates just how much we read Scripture through the lens of our own assumptions, culture, and traditions, and how hard it can be to read well-known texts carefully, attending to what they actually say. It also highlights the power of traditions, and how resistant they are to change. And, specifically, the belief that Jesus was lonely and dejected, cast out amongst the animals and side-lined at his birth, loses sight of the way in which Jesus and his birth are a powerfully disruptive force, bursting in on the middle of ordinary life and offering the possibility of its transformation.

So where has the idea come from? I would track the source to three things: traditional elaboration; issues of grammar and meaning;and unfamiliarity with first-century Palestinian culture.

The traditional elaboration has come about from reading the story through a ‘messianic’ understanding of Is 1.3:

The ox knows its master, the donkey its owner’s manger, but Israel does not know, my people do not understand.

The mention of a ‘manger’ in Luke’s nativity story, suggesting animals, led mediaeval illustrators to depict the ox and the ass recognising the baby Jesus, so the natural setting was a stable—after all, isn’t that where animals are kept? (Answer: not necessarily!)

The issue of grammar and meaning, and perhaps the heart of the matter, is the translation of the Greek word kataluma in Luke 2.7. Older versions translate this as ‘inn’:

And she brought forth her firstborn son, and wrapped him in swaddling clothes, and laid him in a manger; because there was no room for them in the inn. (AV).

There is some reason for doing this; the word is used in the Greek Old Testament (the Septuagint, LXX) to translate a term for a public place of hospitality (eg in Ex 4.24 and 1 Samuel 9.22). And the etymology of the word is quite general. It comes from kataluo meaning to unloose or untie, that is, to unsaddle one’s horses and untie one’s pack. But some fairly decisive evidence in the opposite direction comes from its use elsewhere. It is the term for the private ‘upper’ room where Jesus and the disciples eat the ‘last supper’ (Mark 14.14 and Luke 22.11; Matthew does not mention the room). This is clearly a reception room in a private home. And when Luke does mention an ‘inn’, in the parable of the man who fell among thieves (Luke 10.34), he uses the more general term pandocheion, meaning a place in which all (travellers) are received, a caravanserai.

The difference is made clear in this pair of definitions:

Kataluma (Gr.) – “the spare or upper room in a private house or in a village […] where travelers received hospitality and where no payment was expected” (ISBE 2004). A private lodging which is distinct from that in a public inn, i.e. caravanserai, or khan.

Pandocheion, pandokeion, pandokian (Gr.) – (i) In 5th C. BC Greece an inn used for the shelter of strangers (pandokian=’all receiving’). The pandokeion had a common refectory and dormitory, with no separate rooms allotted to individual travelers (Firebaugh 1928).

The third issue relates to our understanding, or rather ignorance, of (you guessed it) the historical and social context of the story. In the first place, it would be unthinkable that Joseph, returning to his place of ancestral origins, would not have been received by family members, even if they were not close relatives. Kenneth Bailey, who is renowned for his studies of first-century Palestinian culture, comments:

The third issue relates to our understanding, or rather ignorance, of (you guessed it) the historical and social context of the story. In the first place, it would be unthinkable that Joseph, returning to his place of ancestral origins, would not have been received by family members, even if they were not close relatives. Kenneth Bailey, who is renowned for his studies of first-century Palestinian culture, comments:

Even if he has never been there before he can appear suddenly at the home of a distant cousin, recite his genealogy, and he is among friends. Joseph had only to say, “I am Joseph, son of Jacob, son of Matthan, son of Eleazar, the son of Eliud,” and the immediate response must have been, “You are welcome. What can we do for you?” If Joseph did have some member of the extended family resident in the village, he was honor-bound to seek them out. Furthermore, if he did not have family or friends in the village, as a member of the famous house of David, for the “sake of David,” he would still be welcomed into almost any village home.

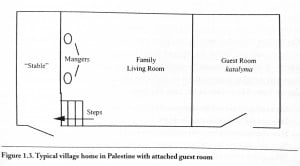

Moreover, the actual design of Palestinian homes (even to the present day) makes sense of the whole story. As Bailey explores in his Jesus Through Middle-Eastern Eyes, most families would live in a single-room house, with a lower compartment for animals to be brought in at night, and either a room at the back for visitors, or space on the roof. The family living area would usually have hollows in the ground, filled with hay, in the living area, where the animals would feed.

Moreover, the actual design of Palestinian homes (even to the present day) makes sense of the whole story. As Bailey explores in his Jesus Through Middle-Eastern Eyes, most families would live in a single-room house, with a lower compartment for animals to be brought in at night, and either a room at the back for visitors, or space on the roof. The family living area would usually have hollows in the ground, filled with hay, in the living area, where the animals would feed.

This kind of one-room living with animals in the house at night is evident in a couple of places in the gospels. In Matt 5.15, Jesus comments:

Neither do people light a lamp and put it under a bowl. Instead they put it on its stand, and it gives light to everyone in the house.

This makes no sense unless everyone lives in the one room! And in Luke’s account of Jesus healing a woman on the sabbath (Luke 13.10–17), Jesus comments:

Doesn’t each of you on the Sabbath untie your ox or donkey from the manger [same word as Luke 2.7] and lead it out to give it water?

Interestingly, none of Jesus’ critics respond, ‘No I don’t touch animals on the Sabbath’ because they all would have had to lead their animals from the house. In fact, one late manuscript variant reads ‘lead it out from the house and give it water.’

What, then, does it mean for the kataluma to have ‘no space’? It means that many, like Joseph and Mary, have travelled to Bethlehem, and the family guest room is already full, probably with other relatives who arrived earlier. So Joseph and Mary must stay with the family itself, in the main room of the house, and there Mary gives birth. The most natural place to lay the baby is in the hay-filled depressions at the lower end of the house where the animals are fed. The idea that they were in a stable, away from others, alone and outcast, is grammatically and culturally implausible. In fact, it is hard to be alone at all in such contexts. Bailey amusingly cites an early researcher:

What, then, does it mean for the kataluma to have ‘no space’? It means that many, like Joseph and Mary, have travelled to Bethlehem, and the family guest room is already full, probably with other relatives who arrived earlier. So Joseph and Mary must stay with the family itself, in the main room of the house, and there Mary gives birth. The most natural place to lay the baby is in the hay-filled depressions at the lower end of the house where the animals are fed. The idea that they were in a stable, away from others, alone and outcast, is grammatically and culturally implausible. In fact, it is hard to be alone at all in such contexts. Bailey amusingly cites an early researcher:

Anyone who has lodged with Palestinian peasants knows that notwithstanding their hospitality the lack of privacy is unspeakably painful. One cannot have a room to oneself, and one is never alone by day or by night. I myself often fled into the open country simply in order to be able to think

In the Christmas story, Jesus is not sad and lonely, some distance away in the stable, needing our sympathy.

Rather, he is in the midst of the family, and all the visiting relations, right in the thick of it and demanding our attention.

This should fundamentally change our approach to enacting and preaching on the nativity.

But one last question remains. This, informed and persuasive, understanding of the story has been around, even in Western scholarship, for a long, long time. Bailey cites William Thomson, a Presbyterian missionary to Lebanon, Syria and Palestine, who wrote in 1857:

It is my impression that the birth actually took place in an ordinary house of some common peasant, and that the baby was laid in one of the mangers, such as are still found in the dwellings of farmers in this region.

And Bailey notes that Alfred Plummer, in his influential ICC commentary, originally published in the late nineteenth century, agreed with this. So why has the wrong, traditional interpretation persisted for so long?

I think there are two main causes. In the first place, we find it very difficult to read the story in its own cultural terms, and constantly impose our own assumptions about life. Where do you keep animals? Well, if you live in the West, especially in an urban context, away from the family of course! So that is where Jesus must have been—despite the experience of many who live in rural settings. I remembering noticing the place for cattle underneath the family home in houses in Switzerland.

I think there are two main causes. In the first place, we find it very difficult to read the story in its own cultural terms, and constantly impose our own assumptions about life. Where do you keep animals? Well, if you live in the West, especially in an urban context, away from the family of course! So that is where Jesus must have been—despite the experience of many who live in rural settings. I remembering noticing the place for cattle underneath the family home in houses in Switzerland.

Secondly, it is easy to underestimate how powerful a hold tradition has on our reading of Scripture. Dick France explores this issue alongside other aspects of preaching on the infancy narratives in in his excellent chapter in We Proclaim the Word of Life. He relates his own experience of the effect of this:

[T]o advocate this understanding is to pull the rug from under not only many familiar carols (‘a lowly cattle shed’; ‘a draughty stable with an open door’) but also a favourite theme of Christmas preachers: the ostracism of the Son of God from human society, Jesus the refugee. This is subversive stuff. When I first started advocating Bailey’s interpretation, it was picked up by a Sunday newspaper and then reported in various radio programmes as a typical example of theological wrecking, on a par with that then notorious debunking of the actuality of the resurrection by the Bishop of Durham!

So is it worth challenging people’s assumptions? Yes, it is, if you think that what people need to hear is the actual story of Scripture, rather than the tradition of a children’s play. France continues:

The problem with the stable is that it distances Jesus from the rest of us. It puts even his birth in a unique setting, in some ways as remote from life as if he had been born in Caesar’s Palace. But the message of the incarnation is that Jesus is one of us. He came to be what we are, and it fits well with that theology that his birth in fact took place in a normal, crowded, warm, welcoming Palestinian home, just like many another Jewish boy of his time.

And who knows? People might even start asking questions about how we read the Bible and understand it for ourselves!

If you would like to see how it might be possible to re-write the Christmas story for all ages in a way which is faithful to this, see this excellent example from Stephen Kuhrt.

I preached on this theme at a Carol Service, and you can read my sermon here.

Additional note

I am grateful to Mark Goodacre for drawing my attention to an excellent paper on this by Stephen Carlson, then one of his colleagues at Duke. The paper was published in NTS in 2010, but is available on Carlson’s blog for free. Carlson presses the argument even further by arguing three points:

1. He looks widely at the use of kataluma and in particular notes that in the Septuagint (LXX, the Greek translation of the OT from Hebrew in the second century BC) it translates a wide variety of Hebrew terms for ‘places to stay.’ He thus goes further than Bailey, agreeing that it does not mean inn, but instead that it refers to any place that was used as lodgings.

2. He looks in detail at the phrase often translated ‘there was no room for them in the kataluma‘ and argues that the Greek phrase ouch en autois topos does not mean ‘there was no room for them’ but ‘they had no room.’ In other words, he thinks that they did stay in the kataluma, but that it was not big enough for Mary to give birth to Jesus in, so she moved to the main room for the birth, assisted by relatives.

3. He believes that Bethlehem was not Joseph’s ancestral home, but his actual family home, for two reasons. Firstly, we have no record of any Roman census requiring people return to their ancestral home. Secondly, he argues that the phrase in Luke 2.39 ‘to a town of their own, Nazareth’ doesn’t imply that they were returning to their home town, but that they then made this their home. We already know this is Mary’s home town, and it would be usual for the woman to travel to the man’s home town (Joseph’s Bethlehem) to complete the betrothal ceremonies. After Jesus is born, they then return together to set up home near Mary’s family.

The kataluma was therefore in all likelihood the extra accommodation, possibly just a single room, perhaps built on the roof of Joseph’s family’s home for the new couple. Having read this, I realised that I had stayed in just such a roof-room, jerry-built on the roof of a hotel in the Old City of Jerusalem, in the lee of the Jaffa Gate, in 1981. It was small, and there was certainly no room to give birth in it!

Buy me a Coffee

Buy me a Coffee

I don’t understand why the author calls Judea, as it clearly was at the time, Palestine, which is an anachronistic use of the word and is still fiercely debated.

The reason is that

a. I am quoting someone else

b. This term was used to describe the region, following the Roman nomenclature, long before it was hijacked as a political term.

Did you know that the Jewish newspaper published in Jerusalem was called the Palestine Post? After the 1948 war it was renamed the Jerusalem Post. The term ‘Palestinian’ as a term for Muslim Arabs in the region was only coined in 1964 as a propaganda move.

But it was called Judea in Roman times by the imperial power, not Palestine (that old Greek usage, never accurate, had long disappeared). The Jews all called their land Israel in the first century. ‘Palestine’ post-1923 referred to Israel and Transjordan together in the British mandate, hence the newspaper name. To call first century Israel “Palestine” is historically false, like referring to Roman France.

Too late. Got my first Christmas card on Monday

https://stevesfreechurchblog.wordpress.com/2013/01/31/an-un-stable-story/

Thanks Steve, that’s really helpful. Good blog overall too!

This is an interesting note:

(A possible reason for the ‘inn’ is that early Latin translations may have used ‘mansio’ – a staying-place – as the equivalent of the Greek ‘kataluma’. Later the word ‘mansio’ came to mean the way-stations of the Roman ‘pony express’, which operated as inns to reduce the expenses.)

Ian – ten years or so after originally writing that piece I’m less confident of that particular suggestion; but still suspect something similar must have happened at that translation point.

Right. Decorations going up.

But it’s not Advent….. yet!!

How about combining the two with tasteful chocolate Christmas tree decorations in the form of the four horsemen of the apocalypse?

I don’t often laugh out loud at the comments section of Ian’s blog, but I really did at this! Thanks Anton. Creative chocolatey interpretations of Death, Judgment, Heaven and Hell might also add to the festive joy…

That’ll do for the advent calendar.

Throw in a few multihorned beasts for good measure.

Co-opt Hieronymus Bosch!

This year I am getting an Old Etonian Advent Calendar – all the doors are opened for me.

Yes, and the translation of TOPOS matters too as you rightly say – ‘room’ as in kitchen, lounge, toilet, bedroom etc, or room as in “there’s not room to swing a cat in here”?

Why was the kataluma full? Two reasons are likely. (Not “because it was Christmas” as one smart child responded!) One reason is relatives arriving for the census, for which people had to register in their ancestral town (Luke 2:1-3). This requirement is also in a papyrus edict of the Roman governor of Egypt Gaius Vibius Maximus in AD104. Roman officials would not have been present on the same day in every place as small as Bethlehem; presumably they moved around according to an advertised timetable, and people registered when the officials passed through their town of origin. In that case the kataluma was already full of other relatives registering. A midwinter nativity would then be unlikely, as travel was difficult in winter when the roads were muddy; census officials probably moved at other times of year. Alternatively the kataluma was full because Jesus was born at one of the three annual pilgrimage festivals: Passover, Weeks, Tabernacles (which Joseph would have been required to attend). These festivals filled Jerusalem, and Bethlehem is a mere five miles away. Luke is not clear about the interval between Joseph and Mary’s journey to Bethlehem and Jesus’ birth, but Mary travelled even when pregnant, to be with a man who trusted her; in Nazareth she would have been mocked for looking pregnant so soon after her wedding. A pregnant woman and her husband would have stayed in the kataluma, and then sought privacy when she went into labour.

But I have heard a third reason why the kataluma was full, from a small child – “Because it was Christmas”…

‘This requirement is also in a papyrus edict of the Roman governor of Egypt Gaius Vibius Maximus in AD104’

That is useful.

Quirinius and Herod the Great did not rule at the same time. And this edict merely asks people to go home to be registered for taxation if they were working away, not to return to their ancestral tribal hometown.

My understanding is that Quirinius (away fighting with the Army) and Sentius Saternius (Political) shared the governorship of Syria during the last years of Herod – Quirinius being senior getting the credit from Luke who was renown for his historical accuracy.

Perhaps, do you have any source for this?

ISBN: 978-1846254161

I believe this papyrus requesting a census (apogaphēs) similar to the one in the Biblical account by Luke can still be found in the British Museum…

From the Wikipedia entry on Gaius there was a link here:

https://www.kchanson.com/ANCDOCS/greek/census.html

which is the document I presume you are referring to.

It has the translation:

“Gaius Vibius Maximus, the Prefect of Egypt, declares:

The census by household having begun, it is essential that all those who are away from their nomes be summoned to return to their own hearths so that they may perform the customary business of registration and apply themselves to the cultivation which concerns them. Knowing, however, that some of the people from the countryside are required by our city, I desire all those who think they have a satisfactory reason for remaining here to register themselves before . . . Festus, the Cavalry Commander, whom I have appointed for this purpose, from whom those who have shown their presence to be necessary shall receive signed permits in accordance with this edict up to the 30th of the present month E . . . ”

There is nothing here about returning to one’s ‘ancestral’ home. Rather, it seems one is to return to one’s “own hearth”. People who are away from home are to do so, unless they get permission to stay where they are.

This fits Luke’s language of returning “each to his own town”. The conclusion must be that Joseph normally lived in Bethlehem, a natural place for someone to live who was of the house and lineage of David.

My view is that the journey in Luke 2:4,5 is that of Joseph travelling with his betrothed to complete the wedding process in his home town, having started from Mary’s home in Nazareth.

See jimmyakin.com on Joseph’s usual residence, which he says was Bethlehem.

Which is to say that Joseph could have been an itinerant builder, following the work where it was to be found and perhaps lodging with relatives in Nazareth when he married Mary.

When Joseph travelled to Bethlehem with Mary, he was not married to her! Luke is clear about this in his choice of word. They must have married in Bethlehem. That they travelled together while betrothed suggests that this was no ordinary journey. Rather, it was the journey from the Bride’s father’s house to the Groom’s house.

I would suggest that Joseph, having accepted the unborn child, was anxious to marry Mary before the birth, so that the child would count as his, and be registered as such for the census.

Marriages in the time were typically arranged. We know that Mary’s family had relatives nearby (Elizabeth also lived in the Judean Hills) and so there is no reason why Joseph ever had to live in or near Nazareth for him to have married Mary.

That is true. The other observation is that itinerant labourers like Joseph frequently had two homes, one with their ancestral family, and the other near their place of work.

One could, of course, add that there was also no star sending its light into a stable (without walls and on an exposed hilltop!). That too is mis-reading, of another (valuable) story, set in a (slightly?) different location, on a definitely later date; thus gutting both stories of their intended message.

I too have difficulty finding any Christmas card that I could countenance sending and, believing astrology to be pagan, have no intention of ‘following’ any ‘star’, no matter how still or bright it may be!

astrology may be ‘pagan’ yet God chose to give meaning to a comet 2000 years ago.

Ah, PC1, we cross swords again!

The Glory of the Lord left the Temple in Ezekiel and moved east.

Ezekiel says the vision he saw from the chebar canal was the Lord.

It travels in a straight line.

A straight line from Jerusalem east hits the Chebar canal.

It came from the north to Ezekiel. That is, it moved south a little.

The wise men in the east, that is, around the vicinity of Ezekiels vision, saw a ‘star’ moving .

I believe this ‘star’ was the Glory of the Lord moving west. This time, straight over Bethlehem.

The Glory never came to dwell in Herod’s temple like it had in Solomon’s Temple, nor in Moses’ Tabernacle.

It must therefore have come back to where a new ‘tent’ was waiting.

If this is not right then where is the Glory now? Still in Mesopotamia?

It makes sense to me that the glory that followed the Israelites into exile would return to The Temple Ezekiel planned out.

All sewn up. No need for another temple in Jerusalem because Jesus is The Temple where God dwells.

I suspect, Steve, we are looking at it through different lenses. Me from a more scientific pov and you from a creative. No need to cross swords, but mine’s bigger!

🙂

My chariot/throne is only 20 cubits cubed but extremely bright. Probably only 2000 ft up.

I think this piece makes lots of extremely valuable points, especially about not putting Jesus in a “poor-person-box” for us to pity at Christmas. But I also have a sense of deja vu, Ian! Your “Not a Stable” piece is itself a just-before-Advent tradition…

It is!

The cave tradition/interpretation of kataluma is wrong as well! I understand there is a cave between Jerusalem and Bethlehem?

Thanks, Ian, good to read this (again!) as Advent approaches. In my previous parish, I had the staff team study together the nativity narratives in the summer. It’s fascinating how the absence of cultural distractions helped to focus on what the narrative actually says, rather than what we assume it says.

Not long after I wrote the blog piece I linked above, Stephen Fry’s programme Qi did Christmas – and quite rightly he was scathing about the absurdity of the bureaucrats sending Joseph to register at a town he didn’t live at. “Made up because prophecy needed Jesus born at Bethlehem…” he said. I then wrote to the ‘Qi elves’ contact address with the substance of the blog. Recently the new Qi with Sandi Toksvig returned to the subject – and gave the ‘no inn’ explanation. They still haven’t sent me a scriptriter’s fee, though!!

Seriously… well done!

But maybe they don’t pay “scriptriter’s ” fees. (Winks).

Ian – maybe I shoud have avoided the typo in ‘scriptwriter’ (winks

Or you could have said “scriptrighter”.

Catholic apologist Jimmy Akin details on his website his debste with Bart Ehrman in which Akin argues that Joseph actually had his family home in Bethlehem. Akin also references the decree from the Roman governor of Egypt Gaius Vibius Maximus in AD 104.

See jimmyakin.com for details.

Yes, Christmas as we have it today is merely a conglomeration

of many cultural aspects. Some churches have a history of adding pagan symbols to Bible narratives.

The ideas presented here are not novel as many commentators over the past few centuries have made similar observations. Modern commentators I think Speculate in the opposite direction, this current offering seems to be replete with speculations

No doubt the birth of Jesus was not under ideal circumstances and His first cradle was not ideal; He may well have been born in a public communal place.

“the ostracism of the Son of God from human society, Jesus the refugee. This is subversive stuff.”[ France]

Jesus not a refugee, what not even in Egypt?

Immanuel, which means “God with us” (Matthew chapter 1: v 23is another name for Jesus. His birth and life is a message of good news for us because it means we are never alone. It doesn’t matter how hard or hopeless our situation may appear to be, God is there for us. We don’t have to journey through our challenges and struggles alone. He understands them. He walks them alongside us.

The supernatural birth of Christ, his miracles, his resurrection and ascension, remain eternal truths, whatever doubts may be cast on their reality as historical facts David Friedrich Strauss

There is no better time than now, this very Christmas season, for all of us to rededicate ourselves to the principles taught by Jesus the Christ. It is the time to love the Lord, our God, with all our heart – and our neighbors as ourselves. this Thomas S. Monson

Thus saith the Lord, Learn not the way of the heathen . . . for the customs of the people are vain,” Jeremiah 10:1-3

The institutions of holy days by God were solemn days

Ex. 10:9, Amplified Bible

Moses said, “We will go with our young and our old, with our sons and our daughters, with our flocks and our herds [all of us and all that we have], for we must hold a feast to the LORD.”

Would that we all did.

I’ve secretly wanted to put a dragon in as part of nativity scenes in churches I’ve been in. Too subversive I suppose. Ian would approve I’m sure .

Just realized it

was probably his idea in the first place….its a great one…

Screwtape beat you to it!

He laps up the laughter at mocking nativity sketches

from unbelieving, secular, skeptics.

Try Wales?

As in Prince?

cf. Prince of Peace

Ian has written about this! See his commentary on the Dragon at the Nativity, Rev 12.1-6.

(Incidentally, Ian, I am reading your commentary now with profit and pleasure.)

Thanks James.

BTW,

This off topic (on reflection it fits with your Revelation citation) but it corroborates our host’s biblical exegesis of Son of Man and the coming of the Son of Man. It is not his second advent.

It is by a Biblical Scholar.

Well worth lending an ear for a few edifying minutes.

The TriumphantSon of Man.

A short podcast from today.

“The Triumphant Son of Man” from Ligonier Ministries https://www.ligonier.org/podcasts/things-unseen-with-sinclair-ferguson/the-triumphant-son-of-man

On reflection, it dovetails with Revelation 12:1-6

Oh good! Thanks.

I once added the Dr Who Tardis to a stained glass window, part of a sermon thing…

Some “churchholyperson” removed it!

No.

It was the teleological Dr. who didn’t want his copyright breached, misused, made in his shape -shifting image.

Thank you. It seems the serpent is to blame….

The Tyndale House podcast on YouTube “The Nativity: fact or fiction?” features an interview with the principal Peter Williams and discusses the familiar questions. One interesting point is that about 16 mi utes Peted references a 2019 CUP book by Sabine Huebner of Basel university in which she argues that the title for Quirinius actually coverd a range of offices.

Numerous articles are available on the Tyndale House website, including Ian’s on the non-stable.

Can we also stop assuming that the journey to Bethlehem took place just before the birth! There is no evidence for this in the Bible or elsewhere.

To my mind the most likely explanation for Mary to leave Elizabeth just before John the Baptist was born, was to return to Nazareth after agreeing with Joseph to complete the marriage as soon as possible and return to Bethlehem before the ‘bump’ showed.

Good observation!

And there’s no mention of a donkey either. they could have travelled in caravan with many people using all sorts of modes of transport. When Jesus was 12 years old they travelled in convoy. I expect they did the same on every journey.

And therefore the ‘Star’, if it appeared at conception, would move to Nazareth then back to Jerusalem and down to Bethlehem. From the east it would be seen in the western sky and to move north, stop, then slowly south, directly above Mary. When the wise men arrived in Jerusalem the star would seem to be due south. I’m assuming the ‘Star’ is the angel who appeared to Mary, The Glory returning from exile in Babylon.

Ian,

I know I am late commenting on the post about Jesus being born in a hosue vs. being born in a stable or cave, but I have a query. I’m fine with your argument, except for one issue. According to Luke, the shepherds went into Bethlehem and found Mary and the baby. If Joseph, Mary, and Jesus were in a room in a house, how would the shepherds know where Jesus was? Surely they did not knock on every door in Bethlehem until they found a house that had a baby in a feeding trough. How do you suppose the shepherds found the child?

Thanks. They asked! Bethlehem was not a big place, and it would not have been difficult to ask ‘Where is the house where a baby has been born?’ Everyone in the village would know.