The  Archbishop of Wales, Dr Barry Morgan, is the longest-serving Primate in the Anglican Communion. Yesterday, on the Sunday before his retirement, he was the preacher on the Radio 4 Sunday Morning worship, in which he talked about Jesus’ sacrifice for us which is illuminated, but can never be exhausted, by examples of human sacrifice. He then raised a key question in relation to God’s compassion and inclusion: why would anyone be opposed to it? His answer is worth reflecting on carefully.

Archbishop of Wales, Dr Barry Morgan, is the longest-serving Primate in the Anglican Communion. Yesterday, on the Sunday before his retirement, he was the preacher on the Radio 4 Sunday Morning worship, in which he talked about Jesus’ sacrifice for us which is illuminated, but can never be exhausted, by examples of human sacrifice. He then raised a key question in relation to God’s compassion and inclusion: why would anyone be opposed to it? His answer is worth reflecting on carefully.

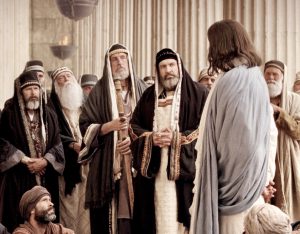

How then is Jesus God’s light to our world? It is because of His compassion and acceptance of all kinds of people in the gospels since He believed compassion was God’s defining characteristic towards humanity. Why should anyone object to that? It was because the religious authorities of His time regarded God’s chief characteristic as holiness, based on the Book of Leviticus, which said people should reflect God’s holiness, and so it was their task to protect that holiness.

Holiness meant having nothing to do with anything that was regarded as unclean or impure. Tax collectors were to be avoided because they did so on behalf of a foreign power – seen as impure. People who were sick were seen as unclean because the terribly twisted common belief was that their wrongdoing was responsible for their sickness. The poor were regarded as impure because wealth was seen as a blessing from God. Men were [apparently] seen as more pure than women because of menstruation and child-bearing.

Jesus turned this system on its head by touching and mixing with all those regarded as impure and unclean – lepers and haemorrhaging women, tax collectors and sinners. He ate with all kinds of people, women included, where sharing a meal was regarded as a sign of acceptance and welcome. He told stories such as the Good Samaritan that were critical of the purity system. The priest and Levite ignored the injured man because contact with death or illness was seen as a source of impurity, whereas the Samaritan, regarded by Jewish society as belonging to an impure race acted compassionately towards the man on the Jericho road.

So too the father of the prodigal runs out to greet his son – something no Jewish father would have done because the son had put himself beyond respectable society by demanding his share of his inheritance before his father’s death, had squandered it all in riotous living and ended up looking after pigs so making himself impure for a multiplicity of reasons. None of that mattered, Jesus said, to a God whose nature was that of forgiveness and mercy. (from 17.10 to 19.40 in the programme).

There are some serious problems with this reading of the gospels, pitting compassionate and welcoming Jesus against the nasty, obsessive, Jewish religious authorities. The first, and most obvious, is that Jesus himself did actually appear to be concerned with holiness, even if his interpretation of the implications of that was different from the Pharisees. The core of his preaching was that ‘the kingdom of God is at hand’ and that this called for both repentance and faith. It is commonly claimed that the word for repentance, metanoia, meant ‘to change one’s mind, to think again’, but in fact it is used in the Greek Old Testament (the Septuagint) to translate the Hebrew shuv, meaning to ‘turn’ from sin. So central to Jesus’ proclamation to his hearers is that they needed to turn from their sins, their unholiness, in order to receiving the kingdom of God that he was bringing in his teaching, healing and deliverance.

This is made abundantly clear in the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew 5 to 7, where Matthew gathers together Jesus’ teaching on particular themes. Far from relaxing the demands of holiness outlined in the law, Jesus appears to raise the bar: it is not good enough simply to act according to the commandments—you also need to turn from any internal ambiguity about these demands. (Compare the closely related ethics of the letter of James, where we are to imitate God in being without a trace of double-mindedness.) In amongst this, Jesus demands not less holiness than the Pharisees, but more:

For I tell you that unless your righteousness surpasses that of the Pharisees and the teachers of the law, you will certainly not enter the kingdom of heaven. (Matt 5.20)

‘Righteousness’ in Matthew (a term which comes seven times) has a very Jewish sense here of ‘doing the right thing, as God requires.’ During his teaching in the temple area, towards the end of the gospel, Jesus makes the importance of the Pharisees’ teaching even clearer:

So you must be careful to do everything they tell you. But do not do what they do, for they do not practice what they preach. (Matt 23.3)

There is absolutely no doubt both that Jesus exercised a radical approach to table fellowship (as Morgan points out) and that this offered a serious challenge to the status quo. But it is far from clear that such fellowship suggested that holiness didn’t matter, or that it was about inclusion regardless of response. Jesus’ explanation, that he has come to call ‘not the righteous but sinners’ is left slightly ambiguous in Matt 9.13, but both Mark 2.17 and Luke 5.32 make it clear: ‘I have come to call sinners to repentance’. (The ESV helps us out if we have any lingering uncertainty: ‘I have come to call those who know they are sinners and need to repent.’) Jesus is radically inclusive: he includes all in the call to leave sin behind and live a life of holiness. This is reinforced in his criticism of the Pharisees in Matt 23.23:

Woe to you, teachers of the law and Pharisees, you hypocrites! You give a tenth of your spices–mint, dill and cumin. But you have neglected the more important matters of the law–justice, mercy and faithfulness. You should have practiced the latter, without neglecting the former!

Note his final comment: in Matthew, Jesus appears to support the commitment to detailed observance, provided it does not undermine the observance of ‘weightier matters.’ In saying this, Jesus is standing four-square in the OT prophetic tradition found in Is 58.6–12 and elsewhere. From Barry Morgan’s sermon, you might get the impression that to follow Jesus meant that you needed to stop being a Jew, but from the gospels and Acts the early Christians looked much more like a Jewish renewal movement than anything else, and there is good evidence that Jewish believers in Jesus felt no need whatever to stop being Jewish, even after the growth of the Gentile mission.

It is particularly unfortunate that Morgan offers this ‘Jesus v the Jews’ dichotomy two days after Holocaust Memorial Day, not least because of the theological tradition within which this approach stands. The contrast between ‘legalistic Judaism’ and ‘liberating Jesus’ can be traced back to Martin Luther, but it became particularly pronounced with the rise of Liberal Protestantism, starting with the work of David Strauss. A key concern of this movement was to use critical ‘scientific’ historical method to separate the ‘authentic’ actions and sayings of Jesus from those added later by the early church as mythology about Jesus; this approach is continued by a group who call themselves ‘The Jesus Seminar.’ One of the key criteria used to determine authentic material is the ‘criterion of dissimilarity‘, which only regards as authentic things Jesus did and said which were neither characteristic of Jesus’ own Jewish context, nor were taken up by Jesus’ earliest followers. There is a methodological problem here; imagine if someone described your life by referring only to ways in which you differed from your own culture and context? The result is bound to be an eccentric and inaccurate portrayal. But there is a deeper philosophical problem here: this approach offers an unJewish and then anti-Jewish portrait of Jesus. It has long been recognised that this way of reading the NT fatally weakened the Protestant churches in Germany and led to their failure to oppose Hitler’s anti-Semitism.

Along with providing historical credibility to Christian faith, Liberal Protestantism also sought to remove the supernatural or ‘religious’ elements, making the gospel a message of social change—and Barry Morgan does the same by interpreting the ‘kingdom of God’ in terms of social inclusion, rather than in terms of repentance and belief.

The theological goal of the Reformers and their successors was to align themselves with Jesus against legalism as part of the justification for separation from the Roman Catholic Church. So the dynamics of this approach and its application look something like this:

| Good | Bad | |

| In the NT | Liberating Jesus | Legalistic Jews |

| In the Reformation | Liberating Protestants | Legalistic Catholics |

But in Morgan’s sermon, he makes a particular reference to Leviticus as part of the problem—despite the fact that Jesus reaches for Leviticus 19.2 in Matt 5.48 when commanding holiness, and for Lev 19.18 ‘Love your neighbour as yourself’ when asked to name the greatest commandment (alongside Deut 6.4). Why would Morgan do this? I think because he is particularly committed to the acceptance of same-sex unions as on a par with traditional understandings of marriage, and dislikes any reference to Leviticus as offering support for the traditional view. He appears to hint at this in the second half of his sermon, where he comments:

We, too, live in a world where some show hatred towards those who do not live pure lives as defined by them. And this lack of tolerance of anyone who departs even slightly from the established norms seems in danger of becoming more rather than less fashionable as a way of thinking…

(This cannot really be a reference to wider society, since ‘purity’ isn’t a category in general public debate.) The theological dynamic has now been extended as follows:

| Good | Bad | |

| In the NT | Liberating Jesus | Legalistic Jews |

| In the Reformation | Liberating Protestants | Legalistic Catholics |

| In the present | Progressive Christians | Legalistic ‘traditionalists’ |

The problem, then, with those who oppose Morgan’s advocacy of same-sex unions is that they are like those nasty, legalistic Jews that Jesus clearly opposes. There is a similar dynamic at work when people claim (as they have to me) that Paul would accept same-sex relations if he had encountered the kind of partnerships that we now know of. But this demands that, as Morgan does with Jesus, we remove Paul from the Jewish context of distinctive ethics based on OT teaching, which are central to Paul’s argument in both Romans 1 and 1 Cor 6.

Jesus was in fact a ‘religious’ leader, not merely a social reformer, and he was one who, by and large, accepted with reformation his Jewish ethical inheritance. To ignore or deny this is to be drawn into a very damaging theological direction—and it doesn’t look like it is too good for church growth either.

Follow me on Twitter @psephizo. Like my page on Facebook.

Much of my work is done on a freelance basis. If you have valued this post, would you consider donating £1.20 a month to support the production of this blog?

Hello Ian, I really don’t get the connection between Liberal theology and anti-Semitism that you are trying to make.

I don’t count myself as an academic theologian but I do try to think things through theologically, and while you make a claim about holiness as something that Jesus carries over into the New Covenant he does so without the trappings and mechanisms of the Law that was the basis of Jewish life. I think Jesus does repudiate the purity code with his willingness to touch lepers and the dead, mingling with tax-collectors and sinners etc – and he does this as an example for us and to demonstrate that holiness means something else.

In my limited experience, many evangelicals seem to have recreated the holiness traditions of the OT and seek to bind Christians to codes of behaviour as evidence of their holiness. I think Jesus repudiates that.

A Meme on Social Media this week, reflecting the listing of The Beatitudes as the Gospel reading for the 4th Sunday after the Epiphany, had Jesus thumping his forehead saying “I gave them the Beatitudes and they still keep quoting from Leviticus.” And they do. What struck me as I reflected on the OT selection for the same day – Micah 6:1-8 – was the unequivocal statement by the prophet that the people were the unmerited beneficiaries of God’s grace. Time and again as you read the OT stories, God does good things for the people even though they don’t deserve this. Yet we take a rather arrogant view of that Amazing Grace by thinking this was the very special – new covenant – message of Jesus.

Finally, it seems undeniable to me that Jesus was both a religious leader and a social reformer and I think you are being unfair in your critique of the Archbishop of Wales as someone who seems keen to only acknowledge the latter.

The simple problem is that Dr Morgan’s explanation is only part of the much larger picture of who Jesus is and what he came to do. Nor do I feel a fuller, more theologically-nuanced answer, was necessarily possible without taking the impact away from the primary thrust of his talk: that Jesus offered mercy and forgiveness, not a set of rules.

I generally agree with him anyway. I think it is right to see Jesus as a kind of reactionary figure, causing friction with the Jewish leaders, often knowingly and deliberately, and so I cannot fault him for saying so. To paint the two as utterly opposed is as bad a mistreatment of the gospels as if you were to treat them as essentially the same, but I do not think that line was crossed here. W

To comment briefly on the idea of holiness and how it antagonised the Pharisees, it is my understanding that Jesus upsets them most of all when he tells them that while Holiness of body is important (affirming the Jewish cultural identity of the time), it is essentially meaningless without Holiness of mind (pointing out that identity’s limitations; think of his teaching on adultery for example), and because the former can be controlled by others while the latter cannot, Jesus is perceived not only to be a radical prophet and teacher calling people to repent, but also to be a direct threat to their authority and the social stability that is largely derived from it. I do not think the two are easily separable and it is that latter idea about authority that eventually escalates the situation leading to his death, rather than the explicit substance of what he taught.

There is so much that could be said here, but the answer to your question must surely be no. It is not anti-semitic to be a liberal, because it is not ant-semitic to point out friction where it clearly exists, or to paint a contrast between two worldviews when they disagree. Anti-semitism is prejudice, discrimination or hostility targeted towards the Jews, and there is none of that here.

Just to elaborate on my final paragraph, I am not saying that you are wrong to link some of these ideas with a particular “theological tradition” (replacement theology is what I assume you’re talking about?), as they can and do lead there, but I do feel you’re wrong to place Dr Morgan in that camp.

Is that clearer?

Mat,

You said “Jesus offered mercy and forgiveness, not a set of rules” but that is a terrible half-truth. It is true that Jesus offered, and offers, mercy and forgiveness. The sermon on the mount talks about the ideals we have to aim for. They are harder than the rules of the Pharisees. The ideals are often so hard they are completely impossible for us.

….and here’s the rub: We live in a society that a) doesn’t handle “ideals” at all and b) see “ideals” as exclusionary.

One of Jesus’s ideals in the sermon on the mount says:

“You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall not commit adultery.’ But I say to you that everyone who looks at a woman with lustful intent has already committed adultery with her in his heart.”

Matthew 5: 27-28

I’m a bloke! I cannot but see a very attractive woman (indeed most of TV is predicated on that idea) and I can then only try not to have any kind of lustful intent …but then I now understand St Paul revealing in his letters how he constantly tries to do the right thing and constantly fails.

Our society now sees ideals as something exclusionary and hateful – and society is completely wrong on that when they do not understand an ideal. It is the same with marriage – the ideal is one thing but some people fail at that and are not to be condemned for not reaching some extreme ideal. I have been married for 36 years but my own parents were the original Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor type of people who separated three or four times. they couldn’t stand to be apart but they couldn’t stand being together either!

No your expression of “not a set of rules” is a half-truth.

Clive, with respect, that was what I paraphrased the Dr as saying, not what I said myself. I agree though, it is a damaging half-truth, but that was no Ian’s criticism.

I am defending Dr Morgan against the cry of anti-Semitism, not of lazy preaching.

Mat, I’m afraid that I really do think that ++Morgan is guilty of shallow, lazy preaching – and it’s not even the first time!

Jesus did bring mercy and forgiveness to the fore but he really didn’t remove holiness. He made the requirements harder for all of us and talked of them as ideals we should aim for. For Barry Morgan to emphasize mercy and forgiveness and ignore the rest of Jesus’ teaching is unacceptable.

My point stands.

Weather Dr Morgan is a good exegete or preacher (you think not, and my frame of reference is limited to this specific case so I can’t really say…) is an entirely different question to the one of weather or not this particular ‘liberal’ approach is anti-Semitic.

On that latter question, I say no. On the former, you are quite probably right, but I wasn’t trying to dispute that.

I can see how this discourse could move in an anti-Semitic way, but I don’t see it necessarily doing so. At issue is an understanding that focuses on holiness seen predominantly as purity, vs holiness seen predominantly enacted through love. This was a discussion within Judaism at the time of Jesus (The school of Shamai vs the school of Hillel) and the later was where Jesus seemed to position himself, particularly in the identification of the greatest command.

For the holiness as purity school, pollution was seen as contaminating, wherein when pollution and purity came together then the pure was contaminated. Jesus had a different approach, when pollution and purity came together it was purity that was contagious. The polluted became clean, the dead came to life, the bleeding stopped, the leprosy cleansed. This does not have to be lifted out as contrary to Judaism but is a stream that ran true to it.

Colin,

You wrote: This was a discussion within Judaism at the time of Jesus (The school of Shamai vs the school of Hillel) and the later was where Jesus seemed to position himself, particularly in the identification of the greatest command.

Yet, Jesus’ position on divorce was at odds with Hillel’s permissive view. You’re right about contagious purity and it is the basis for Paul insisting that those converted to Christ should not abandon their unbelieving wives in order to purify themselves from anything alien to their true identity in Christ:

‘To the rest I say this (I, not the Lord): If any brother has a wife who is not a believer and she is willing to live with him, he must not divorce her. And if a woman has a husband who is not a believer and he is willing to live with her, she must not divorce him. For the unbelieving husband has been sanctified through his wife, and the unbelieving wife has been sanctified through her believing husband. Otherwise your children would be unclean, but as it is, they are holy.

In contrast, there are those of the Church’s liberal wing who contradict this: However, the biblical theme is primarily about the overwhelming demand to remain faithful to our covenantal relationship with God through the Spirit (which, as the gospels warn, may challenge conventional family obligations) Thus while it is clear to us as LGBTs when we survey the gay scene, and indeed much of contemporary social life, that casual sex can often be addictive and destructive, we think it is important to remain open to the possibility that brief and loving sexual engagement between mature

adults in special circumstances can be occasions of grace. (http://changingattitude.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/Sexual-Ethics1.pdf)

Thanks for the note re Hillel and marriage/Divorce. I’ll look that up.

Ian, how do you you interpret the parable of the Good Samaritan without one element being purity/concern for holiness vs compassion? Or how do you deal with Mark 7:17f without a contrast between purity as demanded by some parts of Leviticus and what Jesus says is important?

Why blame just liberal Christianity for anti-semitism, when large parts of the evangelical world still contrast liberating Jesus with legalistic Jews?

Do you think the gospels have nothing to say about the Jewish leaders of the time?

And do you think that Christians need to follow the Law?

I have ceased to understand why people who become angry and obsessional about Leviticus 18:22 and make it the last hill to die on don’t do the same thing for Leviticus 18:16 or 18:18 (as they would have before 1907) . Or why they make Leviticus 22:13 an absolute for all time but not Leviticus 22:18. This seems to me cherry picking on a grand scale..

Alan, if you think that is where the majority of evangelicals or ‘orthodox’ Christians are taking their stand, then you don’t appear to have even begun to understand the case for the ‘traditional’ teaching…and this suggests that the ‘listening’ process has completely failed. No decent commentator I know of does anything other than take these texts as part of a much wider canonical argument.

The thing that most strikes me about reading the Gospels is how much of a religious leader Jesus is. I believe that his teaching has social implications, and that the kingdom does too. But it is clear from the Gospels how much Jesus’ main concern was with people’s relationship with God. He was clear that his kingdom is not of this world, and that we are to render to Caesar what is Caesar’s and to God what is God’s. The target of his polemics were the religious leaders, not because they were religious, but because they were not being good religious leaders. His main concern in Jerusalem was the temple and its purity – the only time it is recorded he became angry. His parables are mostly about finding faith, keeping it and sharing it. Even when he teaches on giving to the needy in Matthew it is clear that his main concern is that it is done in the way most acceptable to God (in secret) rather than with how much to give and to whom. Obviously he does teach about loving one another, giving to the needy etc. and his teaching and practice (such as the inclusion of the gentiles and esteeming of women) has wider implications. But you can’t really give careful study to the Gospels and come away with a picture of Jesus who isn’t primarily concerned with one thing: God, and our relationship with him.

It is common to use passages like Luke 7.36-50 and ‘John’ 7.53-8.11 as yardsticks for something being ‘just like Jesus’. (One who does so is Robin Gill; I also had a conversation with Canon Jane Hedges along these lines.) The former comes from a late gospel and is an amalgam of earlier stories and of Luke’s own explicable interests; the latter is one of the two worst attested pericopae among the 4 gospels, though Papias’s independent witness may give it some historical credence.

The Jesus who welcomed and ate with sinners is not therefore a fiction (see the Levi story etc.).

When it comes to history, you just can’t prioritise texts on the basis of how much you like them, or how good they make you feel. Firstly, the core nature of Jesus may be relatively complex; and secondly we need to defer to NT scholars on which are the best-attested elements of the gospel record. Otherwise we are making a Jesus in our own image and it is no surprise that we like (and are not challenged by) that particular Jesus. I’m sure the real Jesus must have challenged people in certain ways.

The Welsh Archbishop isn’t the official spokesman for liberalism; and while I agree about the unfair maligning of Second Temple Judaism, some of the worst examples of caricature Pharisees and Temple authorities have come from evangelicals, presumably because they’re obliged to uphold all of the gospels, which are rife with anti-Semitism.

Just as Dr. Morgan doesn’t represent liberalism, the Jesus Seminar and its Jesus of California doesn’t represent liberal scholarship: the eschatological prophet of Sanders and Allison, reaching back to Schweitzer, is steeped in Second Temple Judaism.

But, by that yardstick (citing an official spokesman, or representative of its scholarship), any critique of liberalism can be summarily dismissed.

Of course, without careful qualification, evangelicals have advanced ‘some of the worst examples of caricature Pharisees and Temple authorities’.

Fair and balanced? I trow not.

Merely a response in kind, David.

Some evangelicals do indeed speak highly of the Pharisees, pointing to the diversity within theological traditions, and why it’d be as unfair to call evangelicalism anti-Semitic as it is to call liberalism anti-Semitic.

So, since we can always claim that a particular person is neither a spokesman, nor official representative of liberalism or evangelicalism, we are rendered incapable of specifying the merits (or demerits) of either wing of the church.

I suppose that one way to bring clarity to this issue would be for you to articulate who or what is representative of liberal Christianity, instead of pointing out that Dr. Morgan isn’t.

To state the obvious: what makes these exchanges difficult is not knowing the views of the participants on the Bible. Often, no doubt, these views are stated in other posts but this needs a search to find them. Would it not be an idea for each post to be prefaced by stating, to put it crudely, whether the poster believes that all the Bible is true, only some of the Bible is true, none of the Bible is true. I believe all the Bible is true. This includes, but is not limited to, the conviction that God and Christ did say and do, are saying and doing, will say and do all that the Bible asserts. Without something like that we may just be passing each other like ships in the night. As I have said elsewhere, and I am quite willing to be challenged, all ‘liberals’ pick and choose the parts of the Bible which support a worldview drawn not from the Bible but imposed upon it. This imposed worldview is fundamentally different from the worldview that is synthesised from the presupposition that all the Bible is true. If people like me are perceived as picking and choosing, then challenge us where we do that and we can respond.

Phil Almond

The majority position of liberal Christians is representative, ditto evangelicals. No single person embodies it. SFAIK, there’s no evidence that the Archbishop’s position is the majority POV.

To my mind, the most obvious problem with Bishop Morgan’s sermon was his false dichotomy between holiness and compassion (by which I presume he means agape love). To my mind, they are two sides of the same thing. Agape love seeks out the unholy and desires that they be transformed to become holy.

I’m among those not sure of the connection with liberalism here. Surely all types of Christian have been guilty of anti-semitism? The contrast between Jesus as befriender of sinners as against the rule-keepers is often made in evangelical churches too, and as you say needs to be made very carefully not to sound anti-Jewish.

Following on from Penelope’s comment, i think your critique of liberalism is well made Ian, but i think a parallel critique needs to be made of evangelicalism. There is the danger of, to adapt your phraseology, “Was Jesus concerned with the heart rather than holiness – and if so, was he rather un-Jewish?” To put it another way, when we imagine Jesus as a Reformation scholar in sandals do we obscure the Jewishness of our scriptures? I think we need to take the hit here, conscious of the rampant anti-Semitism in so much of our evangelical preaching (the caricature circling around interpretations of Jesus’ ministry that are effectively summations of “law is bad, grace is good, ergo, OT bad, NT good.”

Evangelical preaching that law and OT are bad??? Where have you been hearing these things Richard? Jesus’ words in Luke 16:31 refutes that point of view at once, as does Matthew 5:17.

Phil Almond

Of course the Bible refutes that point of view Phil: i am obviously alone in experiencing anti-Semitism in much evangelical exegesis in preaching! By way of example in a different field, in my own area of Christian-Muslim studies, a common evangelical idea is that i come across is that “Islam is a religion of law” (therefore bad) while “Christianity is a religion of grace”, and indeed Islam can be equated to a form of Judaism after the fact.