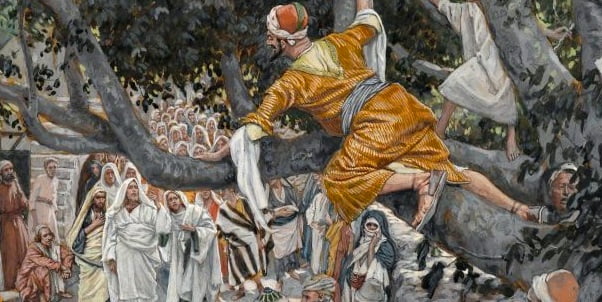

The lectionary reading for the Fourth Sunday before Advent in Year C is the story of Zacchaeus’ encounter with Jesus in Luke 19.1–10, a story found only in this gospel. This short narrative episode has all the elements that make it a perfect Sunday-school story—the witty irony of the ‘big’ man who is too small to see over the crowds; the visual humour of his climbing the tree to see Jesus; the personal touch of Jesus inviting himself to Zacchaeus’ house ‘for tea’ (in the words of the song); and the dramatic change as Zacchaeus offers to give away his ill-gotten gains. So, we might conclude, they all lived happily ever after.

But the story also contains both practical and theological questions. Is Zacchaeus portrayed here as an insider or an outsider? Will he really pay back ‘four times over’ those he has cheated, and why? And (where) do we see the moment of repentance?

Luke is now reaching the end of his ‘journey‘ narrative of Jesus’ ministry that began in Luke 9.51. As he does so, details of location become more specific and realistic; in Luke 18.35 he is ‘approaching Jericho’ and in this episode he has now entered Jericho and is passing through. In contrast to some previous references to location, this is quite realistic; Jesus has travelled South along the Jordan valley, and will now turn West and climbs into the hills of Judea to reach Jerusalem. This means that the sense of divine imperative is increasing (see Luke 18.31); Jesus alludes to this in his response to Zacchaeus ‘I must stay at your house today’. But it also gives a strengthening sense of the connection between successive narrative episodes. The character of Zacchaeus has much in common with the rich (young) ruler (ἄρχων) in Luke 18.18—he is rich (balsam was a product of Jericho, and trade on it would be taxed), he is a ‘ruler’ (ἀρχιτελώνης, ruling tax collector), and the description of Zacchaeus as ‘short’ could suggest youth (compare Matt 19.20). There are significant differences too, in that the ‘ruler’ has kept the commandments, whereas Zacchaeus is perceived to be a ‘sinner’.

There are also important narrative connections with the healing of the blind beggar immediately before (who we know from Mark 10.46 is called Bartimaeus, and from Matt 20.30 that he is not alone). The man cannot see Jesus, but hears the commotion; he asks to see again; and once he can see he follows Jesus. The theme of sight is emphasised all through the Zacchaeus narrative: he wants to see Jesus, but he cannot see him because of the crowd; so he climbs a tree to see him; Jesus looks up at him; and the people see this and are unhappy.

The description of Zacchaeus himself is full of ironic significance. His name is probably a diminutive of Zechariah, so there is no doubt that he is Jewish. But as a tax collector he is working on behalf of Rome, and so supporting those who are oppressing God’s people and colluding with the ‘enemies’ who are preventing God’s people worshipping ‘without fear’ (Luke 1.74). And the name is derived from the Hebrew zchi meaning ‘pure’—but of course his profession is anything but pure! The title of ἀρχιτελώνης does not match any job description we know of from other literature, but does serve to emphasise his influence and power, and Luke adds to this that he is wealthy. If we have followed Luke’s narrative so far, we know that this will not end well. Though Luke does include both the influential and the marginalised amongst those who receive the good news about Jesus, those who are wealthy and powerful are consistently characterised negatively. The coming of Jesus will mean that the ‘mighty are scattered in the imagination of their hearts’ (Luke 1.51); whilst the poor are blessed, the rich will face ‘woe’ (Luke 6.24); and we have just heard that it is hard, or rather impossible, for the rich to enter the kingdom of God (Luke 18.24).

On the other hand, he is a ‘tax collector’, and these, along with sinners, are the very ones that Jesus has come to seek; his final comment in the narrative, that he has come to ‘seek that which was lost’ repeats something that we have heard earlier in the narrative (in Luke 5.29–32). And he is certainly marginalised; though he cannot see over the crowd, there is a strong implication that the crowd will not let him through. He has to dispense with dignity by running, something no self-respecting man in the first-century world would do—just as the Prodigal’s father has done in Luke 15.20. And like a child he climbs the tree to see Jesus. So even within Luke’s establishing characterisation, Zacchaeus is something of a paradox.

What, then, are we to make of someone who is all of these things? In his characterisation of Zacchaeus, Luke pulls the rug from under every cliché, every formula by which people’s status before God might be calculated. (Joel Green, NICNT, pp 667–668)

Added to that is the term ἡλικίᾳ μικρὸς ‘of little span’. The term ‘span’ can refer both to length of life as well as length of body, and we see the ambiguity in translations of the term in Matt 6.27 = Luke 12.25. It is likely to refer to Zacchaeus’ small stature, because of his inability to see Jesus over the crowd—and if so, then gives the narrative a sort of vertical dimension, since he has to climb the tree and get up high to compensate for his small height.

Mikael Parsons notes the response this might well evoke in Luke’s readers. Ancient physiognomy interpreted physical features as indicative of inner dispositions; notice that Luke describes both Jesus and John the Baptist as those who grew ‘in stature’ before God and people (ἡλικίᾳ, Luke 2.52). Someone who was small like Zacchaeus must have been small-minded (mikropsychia) as well as small bodied, meaning that he was petty, greedy and with low expectations. This is expressed not only in Greek sources (Pseudo-Aristotle and Aristotle) but finds its way into the observations of patristic commentators on this passage, Chrysostom and Cyril of Alexandria.

Zacchaeus has been conditioned to have low expectations of himself, and Zacchaeus, the short man, ‘sells himself short’ in terms of living up to his name. (Parsons, Paideia, p 278).

We might say that he has shortchanged himself in terms of his own expectations and what he expects from God! And if that is how Luke’s readers view others, then within the narrative they are identified with the crowd who, through their own prejudice, prevent this man from coming close to Jesus. In previous episodes, Luke has differentiated between the negative reactions of the Pharisees and others, and the more positive attitudes of his own disciples; here, he makes no such distinction, and it appears, in their grumbling, that few have yet really understood Jesus’ message.

When he reaches the tree, Jesus looks up and sees Zacchaeus, and this becomes part of Jesus’ own mission of ‘seeking’ that which is lost (verse 10). Although at first it appears that Zacchaeus has been seeking Jesus, it turns out that Jesus has actually been seeking Zacchaeus. There is a sense of divine imperative in the demand to ‘stay at your house’, and there is no doubt that this is an invitation by Jesus for Zacchaeus to offer hospitality which Jesus accepts, with all the cultural significance of personal association that that carries. Zacchaeus’ immediate response follows the example of those open to God, beginning with Mary’s response to Gabriel, and contrasts with the hesitation and qualification found in both Zachariah and the rich ruler.

Zacchaeus’ financial response in giving half his possessions and paying back fourfold are expressed in the present tense rather than the future. Green notes that this could suggest that this was already Zacchaeus’ habit, and that his castigation as a sinner by the crowd sprang from ignorance of Zacchaeus’ true nature. Thus the story becomes one of recognition by Jesus rather than repentance by Zacchaeus. On the other hand, Parsons notes that the present tense can have a future sense to it (just as in English we say ‘I am seeing my friend tomorrow’ when tomorrow is clearly in the future and ‘seeing’ is clearly in the present) and so repentance is the key note here—and most English translations follow this (‘I will give…’ NRSV; ‘Here and now I give…’ NIV).

The rhetorical effect of Zacchaeus’ negative characterisation confirms the traditional view: Luke’s audience would have heard the story of Zacchaeus as a conversion narrative. (Parsons p 280).

This view is supported by several features of Zacchaeus’ statement. First, he addresses Jesus as ‘Lord’, which is Luke’s own characteristic description of Jesus (though not used in verse 9). Second, although within the events of the narrative, Zacchaeus is responding to Jesus’ grace to him, within the narrative itself his declaration is a response to the grumbling of the crowd. (Note, once again, the actual scene of his declaration is unclear: is it in his own house, so few can hear? or is it in public, so all can hear?). In declaring his repentance, he is absolving Jesus from misconduct in his association with sinners—and this is entirely in line with Luke’s expression of Jesus’ intent, that he associates with the sick to heal them, with sinners to bring them to repentance (Luke 5.31–32). The term συκοφαντέω ‘those I have wronged‘ occurs only here and in Luke 3.14 with reference to soldiers who collude in the exploitation of tax collectors. (It has come circuitously into English in our word ‘sycophant‘!) And it is not clear whether ‘paying back fourfold’ is realistic—but it is the penalty for those who have stolen animals (Ex 22.1, 2 Sam 12.6) and so it signifies Zacchaeus’ admission of guilt (Marshall, NIGTC, p 698). As everywhere else in the NT, inner change (in responding to the challenge and grace of Jesus) is expressed in outer, visible action.

Jesus’ declaration that salvation has come ‘today’ is characteristic of his action in Luke. When reading in the synagogue in Capernaum, he declares that ‘Today, this has been fulfilled in your hearing’; and the thief on the cross is saved ‘today’. There is enormous Christological significance to this claim; ‘Jesus’ (Yeshua) means ‘God saves’, and God’s salvation comes when Jesus visits the house. The promised salvation of God for his people is embodied and effective by the presence of Jesus himself, in fulfilment of the anticipation of salvation at the beginning of the gospel (Luke 1.69, 71, 77). And with that, the walls of prejudice in Jericho come tumbling down.

The image of a traitorous, small-minded, greedy, physically deformed tax collector sprinting in an ungainly manner ahead of the crowd and claiming a sycamore tree is derisive and mocking. But as much as Luke exploits these conventional tropes, his intention is to reverse them in the conclusion to his story. With Jesus’ pronouncement of salvation, the stranglehold of physiognomic determinacy is broken, and the ridicule is turned against itself. Just because Zacchaeus is small in stature does not mean that he must be small in spirit. Just because he is pathologically short does not mean he is to be excluded from the family of God. (Parsons p 280).

If you enjoyed this article, do share it on social media, possibly using the buttons on the left. Follow me on Twitter @psephizo. Like my page on Facebook.

Much of my work is done on a freelance basis. If you have valued this post, would you consider donating £1.20 a month to support the production of this blog?

Yes. Living in France we quickly became aware how complicated the relationship with “collaborators” was. Our neighbour worked in a bank and could see the terrible pressures put on her boss wanting to do their job, needing to keep their job, needing to work alongside officials from both regimes whilst also sympathising with resentments at being occupied plus pressures from the resistance movement, who weren’t always nice people. As you say, Z wasn’t necessarily a bad man. All a bit subtle for a Sunday School story. I think we do kids a disservice portraying Bible stories as neat goodies and baddies, cowboys and indians (and who turns out to have been the real ‘baddies there?!) or superhero stories. I think kids can and need to cope with more than we give them credit for and it’s the teachers wanting the facility of the sensationalist story that’s more fun to teach (gross generalisation).

And I like Bailey’s reflection on Middle Eastern customs, that if a welcome crowd had gone out to welcome someone, even if only out of curiosity, they almost certainly would have prepared food and board too. Greeting only a beggar before getting inside the town limits and then walking straight through and out the other side (as the sycamore grows so large and fast they were only grown outside towns to provide shade for travellers and wood, we had one in our hedge and it was a great nuisance), would have been seriously not pc. Perhaps why this particular incident stuck in people’s memories.

I sympathize with the conquered, who live in the shadow of the Colonizer, and the collusion of a person trying to adapt.

The OT narratives points to total freedom of a people.Some scholars suggest a infantilized of a people depending on the imperialist as a significant other instead of the eternal.

Learning how to die for a tradition is not easy work.Jesus died among the ancients and others sacrificed in the post modern era.What are we going to do.?

“we know from Mark 10.46 is called Bartimaeus, and from Matt 20.30 that he is not alone“

Is it not too coincidental that Matthew has two blind men in Jericho but also two demoniacs in Gadara? Is he not just doubling up for some reason – this has always puzzled me?

Two donkeys on Palm Sunday as well, whereas Mark and Luke only mention one. Perhaps it’s because Matthew is the only one of the three who was actually present on all three occasions so he noted what he personally observed. Mark and Luke on the other hand relied on the first-hand testimony of others so they wrote down only what was essential to the storyline.

Is not the number two of scriptural importance, particularly in relation to corroborative evidence, even if it is untrue, lying testimony? And the Gospel of Matthew is commonly associated with continuity with the Old Testament, targeted at a Hebrew, Jewish audience, is it not? less so Mark and Luke.

John 8:17

Verse Concepts

“Even in your law it has been written that the testimony of two men is true.

1 Kings 21:10

Verse Concepts

and seat two worthless men before him, and let them testify against him, saying, ‘You cursed God and the king ‘ Then take him out and stone him to death.”

1 Kings 21:13

Verse Concepts

Then the two worthless men came in and sat before him; and the worthless men testified against him, even against Naboth, before the people, saying, “Naboth cursed God and the king.” So they took him outside the city and stoned him to death with stones.

Matthew 26:60

Verse Concepts

They did not find any, even though many false witnesses came forward. But later on two came forward,

In any event, Mark 10:46, citing blind Bartimaeus does not contradict Matt 20 :30 as there may well have been two blind beggars on the road (one named, by Mark, for identification purposes) but who were not sitting together, even though both recognised Jesus as the (greater) promised “son of David” the Messiah. The double recognition of Jesus as the Messiah, in Matthew, would have been have been important corroboration, for the Jewish community, especially as it was perceived by those did not have physical eyes to see.

And Bailey comments that in the case of Zacchaeus, repentance basically equated to “recognising that you’ve been found”, or words to that effect. I love this.

Is Zacchaeus the wonderful exception – the rich man who does give his wealth away, who is converted? The rich young ruler who is “religious” fails, but the “sinner” Zacchaeus does not. Do we read Zacchaeus primarily as rich, or primarily as sinner or must we keep both in mind?

Luke’s ongoing continuity puzzles me:

v11 – “As they were listening to this, he went on to tell a parable, because he was near Jerusalem, and because they supposed that the Kingdom of God was to appear immediately”

Is the “as they were listening to this” significant? If it was not there, the text would still make sense. What should we make of the listening to “this”, and is “this” Zacchaeus’ restoration, or just Jesus reply?

In some way (for Luke) the story of Zacchaeus is related to the imminence (or not) of the Kingdom and the parable of the man who would be king who gives money to his slaves. The parable suggests that the Kingdom is not imminent, and Jesus will weep over Jerusalem, which will suffer for not acknowledging the Roman “king”.

Maybe I want to read too much into the “as they were listening” but Luke seems to suggest we should connect the Zacchaeus encounter and the subsequent parable.

In Luke, Zacchaeus is the last specific encounter with a person that Jesus has on his way to Jerusalem and the cross. Firsts and lasts are significant. Climbing a tree made him a target; there are lots of stones in Jericho! Three gifts of grace in this passage could be identified as: hunger to know more about Jesus, acceptance by Jesus, real transformation (what we do with our money reflects where our real security lies).

Great post, Ian!