I have been engaging on and off in the debates about sexuality and Christian discipleship since around 1978, when Buzz magazine (which eventually morphed into Christianity magazine) produced a slightly risky exploration of the issues at stake. Since then, I have noticed that the discussion has shifted ground, both in wider society and within the church. In wider society, it is quite surprising that we have ended up with same-sex marriage, since that had not really been the main demand in the recognition of gay rights, but it has afforded gay relationships with a respectability and status that was desired. Within the church in the UK, much of the debate has been whether the writers of the New Testament either encountered the kinds of relationships that we know, whether they understood the psychology of sexuality in the way we now do—and whether their negative assessment of same-sex sexual relationships in the very few references that we have is correct.

I have been engaging on and off in the debates about sexuality and Christian discipleship since around 1978, when Buzz magazine (which eventually morphed into Christianity magazine) produced a slightly risky exploration of the issues at stake. Since then, I have noticed that the discussion has shifted ground, both in wider society and within the church. In wider society, it is quite surprising that we have ended up with same-sex marriage, since that had not really been the main demand in the recognition of gay rights, but it has afforded gay relationships with a respectability and status that was desired. Within the church in the UK, much of the debate has been whether the writers of the New Testament either encountered the kinds of relationships that we know, whether they understood the psychology of sexuality in the way we now do—and whether their negative assessment of same-sex sexual relationships in the very few references that we have is correct.

But more recently, another response has come to the fore, and it is one I encounter almost every time I speak on this issue. ‘The question of what the texts say is all so complicated—and can we really be sure of what Paul actually meant?’ The reason for this is the explosion of literature (in texts like Matthew Vines’ God and the Gay Christian) which popularise the questioning of what has been a strong consensus that the texts are fairly clear, consistent with one another, and offer a uniformly negative assessment of same-sex sexual activity. Vines’ text is written in an accessible style, and comes with supporting YouTube footage, so has sold well and been very influential—but I find it a very hard read, since there are pretty excruciating and basic errors on just about every page, for anyone who knows about how to read ancient texts. But of course most of Vines’ readers don’t, and Vines himself does not even have a first degree in theology. In relation to the New Testament, he often draws on the work of John Boswell’s Christianity, Social Tolerance and Homosexuality first published in 1980. Boswell’s work did not at the time have much impact on the scholarly consensus of the meaning of the biblical texts, since his methodology was so poor, picking sources that suited his argument and ignoring those that didn’t support his view. But times change, and nearly forty years on much of the church has forgotten some of the basic disciplines of how to make sense of texts.

I have been thinking about two recent examples of this kind of argument—that the texts in Paul are either unclear or do not mean what we thought—one popular and one more scholarly. The popular one can be found in an interview with someone called Ed Oxford, which serves to trail a forthcoming book. It is accessible, and is written in a ‘whodunnit?’ style in which we are led through Oxford’s amazing discoveries about the history of translation of the key terms in Paul. But the methodology is pretty shocking; Oxford seems to think that we understand what terms in the Greek text mean by means of looking at the history of translation, rather than by looking at the prehistory, context and canonical place of these terms. (A similarly poor approach is taking by the substantial Love Lost in Translation which I bought and read and quickly realised why it had been self-published.)

The more scholarly approach is that of Jonathan Tallon, who teaches at Northern Baptist College. Tallon has set up a website with a series of articles on the different texts and issues that arise from them; here I am just considering his article on 1 Cor 6.9.

For me, the problems start with the opening sentences. Tallon poses the issues in these terms: ‘What does Paul say about homosexuality in 1 Corinthians?’ This assumes that there is such a thing as ‘homosexuality’, that we are agreed on what it is, and that Paul thought in such terms. I think each of these assumptions are highly questionable. The next sentence goes on: ‘Is he saying that those who are gay or lesbian won’t enter God’s kingdom?’ He seems immediately to be assuming that, if Paul is expressing a negative assessment of same-sex sex (SSS), then he is also then expressing a negative assessment of same-sex atrtacted people, as if our identity and our patterns of desire and action are fused and can never be separated. As with much discussion on this subject, the assumptions here are implicit rather than explicit, and so might not be noticed by many readers—but they make a massive difference to the shape of the argument and to what is seen to be at stake.

He then points us to Paul’s ‘vice list’ in 1 Cor 6.9–10, which includes the contested terms malakoi and arsenokoitai, but he makes no comment about how such vice lists function in Paul’s writing, how they relate to the immediate context in 1 Corinthians, how they connect with Paul’s pastoral strategy in the letter, or more broadly how they relate to vice lists in either first century Judaism or wider culture (vice lists were common in Stoic literature of the period). Locating the texts in their wider context in the NT and Paul, and locating Paul within his world are actually vital aspects of the task of making sense of texts; I realise that Tallon’s piece is aimed at a popular audience, but this exploration would still be possible in a popular format.

Tallon then discusses the term malakos, the least contentious of the two, and I think I would broadly agree with his conclusions; I am not persuaded by the common conclusion of Tom Wright and others that this is a reference to the passive, ‘receptive’, partner in anal intercourse, with arsenokoites referring to the active, penetrating, partner. This is a possible meaning grammatically, but Tallon is right to point out that it also had a wider moral sense—and the two terms are not grammatically paired with one another, since all the terms in the list are simply separated with ‘neither…neither…neither…’ (oute), a feature which gives the list a particularly high rhetorical impact. But the wording of Tallon’s conclusion is interesting:

My view? I think Paul was referring generally to the morally weak, those who choose to let their lusts lead their actions.

That doesn’t look too far away from a critique of people who let their patterns of desire form their identity.

Tallons’ discussion of the second key term, arsenokoites, is much more problematic. The strong consensus, following the detailed and technical argument of David Wright in in 1984 (in which he comprehensively responds to the arguments of John Boswell) is that Paul has coined the term from the Greek (Septuagint, LXX) of Lev 20.13 in order to describe in the most general terms all forms of SSS. Even if you are not a reader of Greek, you can probably see the very close parallel:

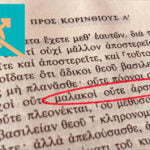

Lev 20.13: καὶ ὃς ἂν κοιμηθῇ μετὰ ἄρσενος κοίτην γυναικός, βδέλυγμα ἐποίησαν ἀμφότεροι

1 Cor 6.9: …οὔτε μοιχοὶ οὔτε μαλακοὶ οὔτε ἀρσενοκοῖται οὔτε κλέπται…

Paul is using a plural form here; the singular arsenokoites is even closer to the text of Leviticus, differing in only one letter from the actual text. To coin a contemporary example, if I exclaimed ‘You are just a to-be-or-not-to-be kind of person’, it is likely that you would recognise a citation from Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Act 3 Scene 1, even if you could not give the reference. It is an unusual phrase; it stands out from my usual terminology; and it refers to a very well-known expression. All these things apply in the same way to Paul’s language here.

Tallon notes that words do not in later use derive their meaning from their constituent parts:

But working out meaning this way is dangerous – a cupboard doesn’t necessarily have cups inside; the chairman of the board doesn’t necessarily refer to an item of furniture. And as for butterflies…

The problem here is that, whilst later use is not determined by the elements of a word, the original coining of the term obviously did. As Wikipedia helpfully points out:

The term cupboard was originally used to describe an open-shelved side table for displaying dishware, more specifically plates, cups and saucers. These open cupboards typically had between one and three display tiers, and at the time, a drawer or multiple drawers fitted to them. The word cupboard gradually came to mean a closed piece of furniture.

Given that there are simply no examples of the word arsenokoites before Paul, or after him except where Christian authors appear dependent on him, it is the original sense of the word we are interested in—and Tallon’s argument here actually undermines his subsequent discussion of later use!

Tallon mentions David Wright’s argument that it comes from Leviticus, but dismisses it quickly, commenting:

Just looking at the construction of the word, and its possible source from Leviticus, suggests that it is referring to those who bed males. But those who bed males, not men.

The reason for that, as Robert Gagnon has pointed out, is that the Leviticus text itself is referring back to the creation text, where God made humanity in his image, ‘male and female he created them’ (not, in Gen 1.27, ‘man and woman’). In other words, Paul is citing Leviticus citing Genesis, and so the rejection of SSS is rooted in the sex dimorphic creation of humanity, something that Paul refers to explicitly in Romans 1.18f.

Tallon then suggests that arsenokoites is often associated with economic exploitation (this is the argument of gay scholar Dale Martin, whose article he lists at the end) but this language is actually absent from the text in Paul. (Martin, in a 2008 biographical article, argues that all sex is ethical as long as the way you have sex reflects the nature of your relationship, be that committed, casual or a one-night stand. I think that would be quite difficult to justify from reading Paul.) Tallon also points to the later Christian concern about paidophthorēseis, translated as ‘corrupting children’, but actually referring to what was thought of as the usual practice in Greek and Roman culture, of older men have penetrative anal sex with younger, receptive males. What is most striking here is that Paul himself does not use this term, nor does he use the usual pair of terms for same-sex lovers, erastus and eramenos. Paul appears to have coined a general term, on the basis of Lev 20.13, to refer in the most general way to SSS. (It is also worth noting that we, like later Christian writers, think that SSS between age-unequal partners the least acceptable, because of our focus on questions of consent and equality. But in the ancient world, this was seen as the most acceptable, and the idea of anal sex between adult males was shocking and unacceptable, since the passive partner was the inferior, and this offended against the idea of the free adult male.)

David Wright’s rather technical article reaches this conclusion:

[I]t is probably significant that the word itself and comparable phrases used by Philo, Josephus and Ps-Phocylides spoke generically of male activity with males rather than specifically categorized male sexual engagement with paides. It is difficult to believe that arsenokoitia was intended to indict only the commonest Greek relationship involving an adult and a teenager. The interchangeability demonstrated above between arsenokoitia and paidophthoria argues that the latter was encompassed within the former. A broader study of early Christian attitudes to homosexuality would confirm this.

Robert Gagnon, well-known commentator in this area, offered a substantial argument on the meaning of these terms in response to the interview with Ed Oxford I mentioned earlier:

As for whether *Paul* intended to limit the word arsenokoitai to men who have sex with adolescent boys, consider the following:

(1) Clear connections to the Levitical prohibitions of male-male intercourse. The compound Greek word arsenokoitai (arsen-o-koi-tai; plural of singular arsenokoitēs) is formed from the Greek words for “lying” (verb keimai; stem kei- adjusted to koi- before the “t” or letter tau) and “male” (arsēn). The word is a neologism created from terms used in the Greek Septuagint translation of the Hebrew Levitical prohibitions of men “lying with a male” (18:22; 20:13). (Note that the word for “lying” in the Greek translation of the Hebrew Levitical prohibitions is the noun koitē, also meaning “bed,” which is formed from the verb keimai. The masculine –tēs suffix of the sg. noun arsenokoitēs denotes continuing agency or occupation, roughly equivalent to English -er attached to a noun; hence, “(male) liers with a male.”)

That the connection to the absolute Levitical prohibitions against male-male intercourse is self-evident from the following points: (a) The rabbis used the corresponding Hebrew abstract expression mishkav zākûr, “lying of/with a male,” drawn from the Hebrew texts of Lev 18:22 and 20:13, to denote male-male intercourse in the broadest sense. (b) The term or its cognates does not appear in any non-Jewish, non-Christian text prior to the sixth century A.D. This way of talking about male homosexuality is a distinctly Jewish and Christian formulation. It was undoubtedly used as a way of distinguishing their absolute opposition to homosexual practice, rooted in the Torah of Moses, from more accepting views in the Greco-Roman milieu. (c) The appearance of arsenokoitai in 1 Tim 1:10 makes the link to the Mosaic law explicit, since the list of vices of which arsenokoitai is a part are said to be derived from “the law” (1:9). While it is true that the meaning of a compound word does not necessarily add up to the sum of its parts, in this instance it clearly does.

(2) The implications of the context in early Judaism. That Jews of the period construed the Levitical prohibitions of male-male intercourse absolutely and against a backdrop of a male-female requirement is beyond dispute. For example, Josephus explained to Gentile readers that “the law [of Moses] recognizes only sexual intercourse that is according to nature, that which is with a woman. . . . But it abhors the intercourse of males with males” (Against Apion 2.199). There are no limitations placed on the prohibition as regards age, slave status, idolatrous context, or exchange of money. The only limitation is the sex of the participants. According to b. Sanh. 54a (viz., tractate Sanhedrin from the Babylonian Talmud), the male with whom a man lies in Lev 18:22 and 20:13 may be “an adult or minor,” meaning that the prohibition of male-male unions is not limited to pederasty. Indeed, there is no evidence in ancient Israel, Second Temple Judaism, or rabbinic Judaism that any limitation was placed on the prohibition of male-male intercourse.

(3) The choice of word. Had a more limited meaning been intended—for example, pederasts—the terms paiderastai (“lover of boys”), paidomanai (“men mad for boys”), or paidophthoroi (“corrupters of boys”) could have been chosen.

(4) The meaning of arsenokoitai and cognates in extant usage. The term arsenokoitēs and cognates after Paul (the term appears first in Paul) are applied solely to male-male intercourse but, consistent with the meaning of the partner term malakoi, not limited to pederasts or clients of cult prostitutes (see specifics in The Bible and Homosexual Practice, 317-23). For example, the 4th century church historian Eusebius quoted from a 2nd-3rd century Christian, Bardesanes (“From the Euphrates River [eastward] … a man who … is derided as an arsenokoitēs … will defend himself to the point of murder”), and then added that “among the Greeks, wise men who have male lovers are not condemned” (Preparation for the Gospel 6.10.25). Elsewhere Eusebius alluded to the prohibition of man-male intercourse in Leviticus as a prohibition not to arsenokoitein (lie with a male) and characterized it as a “pleasure contrary to nature,” “males mad for males,” and intercourse “of men with men” (Demonstration of the Gospel 1.6.33, 67; 4.10.6). Translations of arsenokoitai in 1 Cor 6:9 and 1 Tim 1:10 in Latin, Syriac, and Coptic also define the term generally as “men lying with males.”

…

(8) Implications of 1 Tim 1:9-10 corresponding to the Decalogue. At least the last half of the vice list in 1 Tim 1:8-10 (and possibly the whole of it) corresponds to the Decalogue. Why is that important? In early Judaism and Christianity, the Ten Commandments often served as summary headings for the full range of laws in the Old Testament. The seventh commandment against adultery, which was aimed at guarding the institution of marriage, served as a summary of all biblical sex laws, including the prohibition of male-male intercourse. The vice of kidnapping, which follows arsenokoitai in 1 Tim 1:10, is typically classified under the eighth commandment against stealing (so Philo, Pseudo-Phocylides, the rabbis, and the Didache; see The Bible and Homosexual Practice, 335-36). This makes highly improbable the attempt by some to pair arsenokoitai with the following term andrapodistai (kidnappers, men-stealers), as a way of limiting its reference to exploitative acts of male-male intercourse (so Robin Scroggs), rather than with the inclusive sexual term pornoi (the sexually immoral) that precedes it….

It is worth reading the whole comment for a comprehensive argument.

I know Robert Gagnon a little; I have attended seminars at which he has spoken, and we once visited the British Museum together. I don’t agree with all of his arguments, and we have very different political outlooks. But what is interesting about his argument here is the number of mainstream, theologically liberal, scholars who cite him. William Loader’s research on sexuality in the New Testament cites Gagnon several times on each page when addressing the issues they both study. Loader recognises the quality of Gagnon’s research and the force of his argument about what Paul actually meant—though Loader takes the diametrically opposite view to Gagnon on the ethical issue of same-sex relationships. He simply thinks that Paul, and therefore Gagnon, is wrong.

Similarly, it is worth noting the approach of the Pauline scholar E P Sanders, in his 850-page magnum opus on Paul from 2015. Sanders had a huge impact on Pauline scholarship with his argument about the nature of first-century Judaism, giving rise to the so-called ‘New perspective on Paul’. This latest volume summarises and draws together his thinking on Paul, rather than engaging with recent arguments—but he has added in (for some reason) a 60-page assessment of Paul and SSS.

Sanders makes some very interesting comments about the function and role of Paul’s vice lists, noting their connections with both Jewish and Stoic lists, though also noting the characteristic emphasis on idolatry and sexual immorality that was a consistent feature of Diaspora Judaism in the period. He also notes the function of the vice lists as a rhetorical device; Paul’s actual pastoral handling of individual cases of sin was quite different—which seems to me to be highly pertinent in the current context. But his conclusion is in line with David Wright, Robert Gagnon and William Loader: Paul is rejecting every form of SSS, drawing on the text of Lev 20.13, and in doing so he sits squarely within the tradition of Diaspora Judaism which took a very similar view. This is striking, Sanders notes, since in many other ways, Christianity adopted many other aspects of pagan culture; this issue was the one where there was sharpest disagreement between Christianity’s two ‘parents’ of Judaism and Graeco-Roman culture, and on the question of SSS, it came down unequivocally on the side of Judaism. He concludes:

Diaspora Jews had made sexual immorality and especially homosexual activity a major distinction between themselves and gentiles, and Paul repeated Diaspora Jewish vice lists. I see no reason to focus on homosexual acts as the one point of Paul’s vice lists that must be maintained today.

As we read the conclusion of the chapter, I should remind readers of Paul’s own view of homosexual activities in Romans 1, where both males and females who have homosexual intercourse are condemned: ‘those who practice such things’ (the long list of vices, but the emphasis is on idolatry and homosexual conduct) ‘deserve to die’ (1.31). his passage does not depend on the term ‘soft’, but is completely in agreement with Philo and other Diaspora Jews. (p 373)

This conclusion is in line with other commentators who have looked carefully at the issue:

It is very possible that Paul knew of views which claimed some people had what we would call a homosexual orientation, though we cannot know for sure and certainly should not read our modern theories back into his world. If he did, it is more likely that, like other Jews, he would have rejected them out of hand….He would have stood more strongly under the influence of Jewish creation tradition which declares human beings male and female, to which may well even be alluding in 1.26-27, and so seen same-sex sexual acts by people (all of whom he deemed heterosexual in our terms) as flouting divine order. (William Loader, The New Testament and Sexuality, p 323-4)

Where the Bible mentions homosexual behavior at all, it clearly condemns it. I freely grant that. The issue is precisely whether that Biblical judgment is correct. (Walter Wink, “Homosexuality and the Bible”)

I think the texts in Paul are much clearer than current discussion would have us believe.

To close this longer-than-usual post, I want to offer four final pastoral observations.

The first relates to Bible translation. It is clear that translators have wrestled with the translation of these two terms in Paul, even in different languages, and come up with some very different answers. Ed Oxford talks about how he discovered the history of German translation of key texts in the Old and New Testaments:

So we went to Leviticus 18:22 and he’s translating it for me word for word. In the English where it says “Man shall not lie with man, for it is an abomination,” the German version says “Man shall not lie with young boys as he does with a woman, for it is an abomination.” I said, “What?! Are you sure?” He said, “Yes!” Then we went to Leviticus 20:13— same thing, “Young boys.” So we went to 1 Corinthians to see how they translated arsenokoitai (original Greek word) and instead of homosexuals it said, “Boy molesters will not inherit the kingdom of God.”

I then grabbed my facsimile copy of Martin Luther’s original German translation from 1534. My friend is reading through it for me and he says, “Ed, this says the same thing!” They use the word knabenschander. Knaben is boy, schander is molester. This word “boy molesters” for the most part carried through the next several centuries of German Bible translations. Knabenschander is also in 1 Timothy 1:10. So the interesting thing is, I asked if they ever changed the word arsenokoitai to homosexual in modern translations. So my friend found it and told me, “The first time homosexual appears in a German translation is 1983.”

If this is all true, then it is extraordinary. There is simply no reason to translate the Hebrew zakar in Lev 18.22 and 20.13 with the term ‘young boys’ and I know of no English translation that does so. What is happening here is that the translators have conflated the term arsenokoites that Paul does use with the later term paidophthorēseis that Paul doesn’t use—and, seeing the connection with Leviticus, have then read that concern back into the Old Testament! It is a bizarre approach to translation.

Sanders makes a very interesting observation, which I have not come across before, but which explains why there has been such difficulty in translation in the past.

Homosexual activity was a subject on which there was a severe clash between Greco-Roman and Jewish views. Christianity, which accepted many aspects of Greco-Roman culture, in the case accepted the Jewish view so completely that the ways in which most of the people in the Roman Empire regarded homosexuality were obliterated, though now have been recovered by ancient historians. (p 344)

It is one of the many ways in which we now know a lot more about the first century than e.g. Christians in the fourth century, not as a matter of modern hubris but as a result of a two centuries of interest in the classical world. (If you want to explore the literature on Roman attitudes to sex, read this remarkable post by my friend John Pike.) Prior to the modern era, translators were, on these two words, somewhat flying blind.

Many English translations, using language like ‘homosexual abusers’ do capture the rhetorical force of Paul’s language—but they add a whole lot of contemporary cultural baggage at the same time. Perhaps the best way to translate the terms might be to use ‘softies’ for the first, capturing the meanings of malakos as both ‘effeminate’ and ‘morally weak’, and ‘men who have sex with men’ for arsenokoites, reflecting both its etymology and its close connection with Lev 20.13.

The second issue is the confusion that has been created in the debate. It suits those who want to see the Church change its teaching for most members of the Church to say ‘It is all so complicated, and the Bible is not really as clear as I thought’. That climate is created by popularised arguments that ignore the whole range of evidence—and give no indication to their readers (who mostly won’t know how to assess this) that there are other issues that need to be considered. For example, I don’t suppose anyone reading Tallon’s article or watching his video will think to ask ‘But what is the cultural context of Paul? And how does his view connect with other Jewish critiques of pagan culture?’ since there is no hint that this might be an important issue. Tallon is right to offer a bibliography—but how many of his readers will actually look up the articles he cites, not least because David Wright’s is published in a specialist journal for which you have to have an expensive subscription? Atomising the debate—isolating one text from another, and isolating the texts from their context—is a common feature of such arguments, and they lead to confusion.

The third issue is our decision in the light of what Paul says. E P Sanders is very interesting in this regard; like many other scholars, whilst he is clear about what Paul means, he does not see Paul’s view as in any sense binding on his own views as a Christian.

Paul’s vice lists are generally ignored in church polity and administration. Christian churches contain people who drink too much, who are greedy, who are deceitful, who quarrel, who gossip, who boast, who once rebelled against their parents, and who are foolish. Yet Paul’s vice lists condemn them all, just as much as they condemn people who engage in homosexual acts (p 372).

Sanders is spot on here: you cannot pick and choose, and if you take Paul seriously on one issue, you must surely take him seriously (or not) on all issues. Sanders’ conclusion is to treat them all as non-binding—but of course there is an alternative response available.

The fourth then is the question of our reception of gay people in terms of our pastoral response. Sanders makes some very interesting observations about the nature and use of Paul’s vice lists.

Homiletically, vice lists gain rhetorical force partly by length and partly by the equation of relatively minor sins with relatively major ones. It might be quite useful for a preacher to gain the audience’s support by condemning major sins (such as adultery and greed), but then to add that there are lots of sins…which are practiced by some of the people in the pews, and that these count as sins too…This has a healthily purgative effect. (p 338).

He also notes that Paul’s own pastoral strategy is not effected by the vice lists, since he handles actual examples of sin in a different way. Besides, the clear assumption is that the things he lists are now in the past: ‘such were some of you. But…’ (1 Cor 6.11). Sanders sums up:

The accusations in his vice lists are not actually directed at the sins of his converts at all (p 339).

Sanders goes further, noting the significance of Paul saying so little about SSS:

[H]omosexual practices are not very important in Paul’s letters. They figures in his vice lists, as do deceit and malice, but he does not elaborate on them; they are only items in a list. We must assume that he did not actually face a case in one of his congregations; if he had, we would hear a lot more about it. (p 345)

Paul’s language on this issue does not offer us a pastoral strategy for relating to gay people, within the church or outside. What it does do, though, is tell us clearly Paul’s understanding of the moral status of SSS, and with him the view both of Judaism and the early church, and following that most of Christian understanding down the centuries. The heated and (in my view unnecessary) debates about these clear texts not only sows confusion, it also makes gay people feel as though they are the subjects of these debates, which I think is unhelpful all round.

So let’s stop constantly debating the meaning of these texts—amongst all exegetical issues in the NT, these are relatively clear. When we do that, we can move on to the more important pastoral issue of how we engage with each other in relationship.

If you enjoyed this, do share it on social media, possibly using the buttons on the left. Follow me on Twitter @psephizo. Like my page on Facebook.

Much of my work is done on a freelance basis. If you have valued this post, would you consider donating £1.20 a month to support the production of this blog?

Yes, the texts are clear enough; and yes, Wink has it right.

Why do my fellow liberals waste so much of their time on this stuff? As most will admit when pushed, they’d ultimately disregard Paul whatever he said (and many are a good deal more flippant than that), so what’s the point? I’ve yet to see a single conservative whose mind’s been changed by ropey exegesis, and since even attempting it implicitly condones a theological position that’s anathema to liberalism, it’s perilously close to arguing in bad faith.

Fellow liberals, please, just drop this. You must be as sick of reading these rebuttals as their authors are of writing them. This is a road to nowhere. Paul was who he was, and said what he said. He’s never gonna be welcome on a Pride march, and this ahistorical eisegesis insults everyone’s intelligence.

Let’s instead make the case on our own terms.

Amen and amen! Preach it, brother!

That’s not the way the battle for truth will be won or lost.

Progressive interpretations don’t need to be better than other interpretations in order to obliterate traditional teaching. All that needs to happen is for Christians to conclude that it is reasonable to hold a different interpretation and still be a Christian: We must, therefore, agree to disagree because otherwise we’ll be accused of the evil act of splitting the church over it!

Then, once truth and falsehood are walking hand in hand, the truth has no meaning anymore. It is utterly devalued.

And when truth has no value, falsehood has free reign.

I’m not interested in unchurching people, but I just don’t see the point of strapping down the epistles and torturing some fantastical meaning out of them.

The only people from whom it’s a necessity are theologically orthodox Christians who want to take a liberal line on sexuality (such as John Boswell, who was both gay and a devout Catholic). Well, whatever gets them through the night, but most liberals shouldn’t waste their time on it.

Have you seen what’s progressing in the Methodist church recently?

A task group was invited to consider sexual issues to see if their teaching, mainly on same sex marriage, should change. They came back with a paper presenting this sort of shoddy Progressive ‘theology’ and Conference is recommending that this should be discussed in the churches before coming back for a final vote next year.

So, for the next year, Methodists will be discussing what they think of it. It’s unlikely the church will make a stand claiming one interpretation is true and the other false (which is what SHOULD happen!). Rather, faced with two ‘possible’ interpretations, they will likely agree that they will continue to walk hand in hand in ‘unity’ as I described it.

So there’s a real life example of the effect of these poor Progressive interpretations being effective, not because they’re any good but because they present an excuse for moving away from truth – on a denominational level.

Hi Ian

Unfortunately I was on holiday when this was published, hence my late and brief response now. Some quick comments:

Quote: ‘Tallon poses the issues in these terms: ‘What does Paul say about homosexuality in 1 Corinthians?’ This assumes that there is such a thing as ‘homosexuality’, that we are agreed on what it is, and that Paul thought in such terms. I think each of these assumptions are highly questionable.’

I agree. They are highly questionable. Sadly, they are usually not questioned enough, and modern understandings of homosexuality are projected back into first century culture. For a short piece on this, you can see the article I wrote at https://viamedia.news/2019/05/17/does-the-bible-really-say-anything-at-all-about-homosexuality-as-we-understand-it-today/

Quote: ‘The next sentence goes on: ‘Is he saying that those who are gay or lesbian won’t enter God’s kingdom?’ He seems immediately to be assuming that, if Paul is expressing a negative assessment of same-sex sex (SSS), then he is also then expressing a negative assessment of same-sex atrtacted people, as if our identity and our patterns of desire and action are fused and can never be separated.’

I do not assume this at all. But I’m addressing the questions that modern audiences (without detailed knowledge of first century culture) might (and do) ask.

On the vice lists: you’re right, I don’t address the genre. This was because, as you inferred, it was for a popular audience, and I tried to keep the videos as streamlined as possible to what I considered the most essential points. (The text on the website is primarily that of the videos, with extra comments added at the end and links to resources).

Quote: ‘Tallon then discusses the term malakos, the least contentious of the two, and I think I would broadly agree with his conclusions’

Thank you! Nice to get some agreement.

Quote: ‘The strong consensus, following the detailed and technical argument of David Wright in in 1984 (in which he comprehensively responds to the arguments of John Boswell) is that Paul has coined the term from the Greek (Septuagint, LXX) of Lev 20.13…’

It actually does not affect the argument greatly either way, but I am less convinced of this. On my to-do list for the future is an article addressing this point – the quick summary is that the creation of the term doesn’t need the Septuagint, and parallel examples exist of similar created terms that are unrelated to the Septuagint. I also think it unlikely that gentile Christians would have got the reference.

Quote: ‘The reason for that, as Robert Gagnon has pointed out, is that the Leviticus text itself is referring back to the creation text, where God made humanity in his image, ‘male and female he created them’ (not, in Gen 1.27, ‘man and woman’).’

Not convincing. I have commented on this argument before. If it was really a reference with Genesis, we would expect at the least females also to be mentioned. Lev. 20:13 mixes man and male, which makes a lot of sense if pederasty is in mind, but a lot less if you’re trying to reference Genesis.

Quote: ‘Tallon then suggests that arsenokoites is often associated with economic exploitation (this is the argument of gay scholar Dale Martin, whose article he lists at the end) but this language is actually absent from the text in Paul.’

It is absent from 1 Cor., but arguably present in 1 Tim. 1:10. The next item after arsenokoites is slave-traders, who would be the ones who procured boy prostitutes. Economic exploitation is also the background in the first recorded use outside of the New Testament in the Sibylline Oracle 2.70-77.10.

Quote: ‘Tallon also points to the later Christian concern about paidophthorēseis, translated as ‘corrupting children’, but actually referring to what was thought of as the usual practice in Greek and Roman culture, of older men have penetrative anal sex with younger, receptive males.’

The first appearance is later, but not by much. It appears in the Didache, the oldest none-NT Christian text we have. I don’t think this is a later concern, I think this is exactly the same concern, but expressed in different terms. Both terms, paidophthoreseis and arsenokoites, appear in similar vice lists in similar positions.

Quote: ‘What is most striking here is that Paul himself does not use this term, nor does he use the usual pair of terms for same-sex lovers, erastus and eramenos.’

I don’t find this striking at all. We don’t actually know whether Paul invented this term (this is just the first time we find it in literature – a very different thing). And I can well understand why Paul and other Christians would be reluctant to use terms (erastus and eramenos) which implied that abusive pederasty had anything to do with love. It should be noted that paidophthoreseis is also a word that first occurs in early Christian literature, just like arsenokoites.

Quote: ‘the idea of anal sex between adult males was shocking and unacceptable, since the passive partner was the inferior, and this offended against the idea of the free adult male.’

This rather underlines how the idea of a faithful, equal partnership was not (and could not have been) a consideration in the ancient world.

Quote: ‘The interchangeability demonstrated above between arsenokoitia and paidophthoria argues that the latter was encompassed within the former. A broader study of early Christian attitudes to homosexuality would confirm this.’

Wright’s argument doesn’t have any evidence. If terms appear to be interchangeable (which Wright admits), the default assumption ought to be that they are interchangeable, not that one means much more than the other or encompasses the other.

Gagnon: I don’t have space to respond in detail. But note that when Leviticus (and Mosaic Law) is referred to by contemporaries of Paul (eg by Philo) they are talking about pederasty as its application.

Quote: ‘Perhaps the best way to translate the terms might be to use ‘softies’ for the first, capturing the meanings of malakos as both ‘effeminate’ and ‘morally weak’, and ‘men who have sex with men’ for arsenokoites…’

No! You have already said how the most culturally acceptable form of male-male sex was men with boys, so why on earth would you translate arsenokoites as ‘men who have sex with men’?!

Quote: ‘For example, I don’t suppose anyone reading Tallon’s article or watching his video will think to ask ‘But what is the cultural context of Paul? And how does his view connect with other Jewish critiques of pagan culture?’ since there is no hint that this might be an important issue.’

In a short video for a popular audience, I cannot cover every issue. But this strikes me as unfair criticism, given I do address some of the most pressing issues and try to give some of the first century cultural background (see also the video/article on Romans).

Quote: ‘Tallon is right to offer a bibliography—but how many of his readers will actually look up the articles he cites, not least because David Wright’s is published in a specialist journal for which you have to have an expensive subscription?’

Sadly, the economics of academic publishing are beyond my control. But I hope that people do find the annotated bibliography useful (and so prevent the atomising of debate): http://www.bibleandhomosexuality.org/bibliography/

Quote: ‘So let’s stop constantly debating the meaning of these texts—amongst all exegetical issues in the NT, these are relatively clear.’

I beg to differ. You basically have three NT texts that are relevant. Two of them use the same word, arsenokoites, used for the first time in known literature. There are clear scholarly differences in how much should be read into this term (I note that you didn’t actually address Dale Martin’s arguments here, but attacked his ethical views). The third (Romans) also generates scholarly debate, with arguments over the context, the references, and whether female-female sex is included or not.

To make the point more directly, here is William Loader (whom you cite approvingly) on 1 Cor. 6:9 and arsenokoites: “Possibly Paul has that whole range of same-sex relations in mind here or possibly particular kinds which would especially illustrate what he means here by ‘unjust’, although he used that term rather widely as the rest of the list indicates and he might have used more specific terms if he had a narrower sense in mind. It is impossible to know for sure’. (Loader, 2010, 32).

If Loader is saying that ‘it is impossible to know for sure’ then the exegetical issues are not ‘relatively clear’ at all, and to pretend they are does a disservice to the church generally.

Hi Jonathan. Can you unpack further the reference to the Sibylline Oracle? I’ve often heard it quoted as you do but can’t see it myself. The immediate context is to do with lying and murder. People tend to quote Dale Martin as if he establishes the economic setting. Rather like Paul in 1 Corinthians 6 Book II seems to be a general list of immoral behaviour. There are references to economic injustice but I can’t see any evidence that makes it a controlling context. Am I missing something? Thanks.

Totally agree with you, James.

Yes there is something 1984 about the way that people (without the training) try to make the texts say the opposite of what they do. But it is a very serious matter that trained scholars in high positions are being so selective in their presentations of the evidence.

Paul was *not* a 21st century western liberal? Perish the thought.

I wholeheartedly concur! These arguments are as desperate as those which try to argue away 1Tim’s prohibition of women in authority.

If you know anything about reading the NT, then you will no that this is no comparison at all. ‘Authentein’ is hapax, and in other contemporary literature implies ‘taking another’s life’; the grammar is odd; there is a symmetry between Paul’s instructions between men and women that is usually ignored; the context of Ephesus was a cult of women who did not need men; and the common translation directly contradicts other Pauline comments about women teaching him, exercising authority over their husbands, receiving gifts of speech from the Spirit which are there to teach the whole community.

You can only think these arguments ‘desperate’ if you are desperately ignorant of the issues here…!

Ian writes:

“….usually pair of terms for same-sex lovers, erastus and eramenos. ”

Both words are linked to the Koine-greek word for love as “eros” from which we equally get the word “erotic”, but they are NOT linked to the Koine-greek word for love as “Agape”.

The argument that all the words for love in Koine-greek are interchangeable is completely unconvincing when ancient languages are characterised by having less words than modern languages, so why would Koine-greek have four words for love when English only has one!

Sanders is a fine biblical scholar, but his ethical reasoning is weak. He says:

Paul’s vice lists are generally ignored in church polity and administration. Christian churches contain people who drink too much, who are greedy, who are deceitful, who quarrel, who gossip, who boast, who once rebelled against their parents, and who are foolish. Yet Paul’s vice lists condemn them all, just as much as they condemn people who engage in homosexual acts (p 372).

I know people in the pew make this kind of argument, but it is so flimsy I’m amazed to see it from the pen of a renowned scholar.

The obvious response is that no one is defending gluttony, greed, deceit, quarrelling, gossip, boastfulness, rebelliousness and foolishness, or proposing services of blessing for those who make such things central to their identity. Many people may do them, but no one is praising them for it or trying to defend it as good.

The more pertinent point surely is that same-sex sexual behaviour is the only item on the biblical vice lists that anyone is trying to get the church to endorse.

Thanks Will. I actually think his point is slightly more coherent that you say, and I think it offers a real challenge.

You say ‘no one is defending gluttony, greed, deceit…’ but in fact I think Sanders is right: many people are. When Christians say that e.g. opposing abortion excuses a national leader from his lies, aggression, racist comments and serial adultery, they are indeed defending this things, or at least ignoring Paul’s teaching and cocking a snook at the impact of Paul’s vice lists.

I am always struck when I visit the US how much more accepted multiple divorces and remarriages are in the church than in the UK. Sanders is pressing a point of integrity: you cannot say one item on this list is ‘the test’ of the church when you have, de facto, accepted the others.

No one is praising those things or wanting to celebrate them in church. Christians who support Trump or Boris, or Corbyn, or Clinton, or almost any politician – they are (almost) all a pretty dubious bunch in one way or another – do so as a calculation of what is best (or least worst) for their country (and the world) at this point in time given the other possible options.

For Trump I think for Christians it’s to do with religious freedom, abortion and the Supreme Court (and not being Hillary Clinton and part of the fanatically pro-abortion and LGBT Democrats). For Boris it’s mostly Brexit (some Christians see this as very important for various reasons), though he has appointed notably more conservatives (small c) than May, even though he is himself much more liberal than conservative.

Calculations as to who one supports politically out of the available options can’t easily be translated into a moral code – look at the OT kings whom God uses. And certainly offering qualified support for political leaders with morally dubious personal lives does not equate with endorsing and celebrating the vices/sins themselves, which is what we are talking about here.

While I could accept reluctant Christian support of the Don on the basis of a Two Kingdoms doctrine (i.e., civil politics is inevitably a sewer, to be judged by different standards to God’s kingdom), the stomach-churning adulation of this dissolute slumlord from Christian leaders who ought to know better goes way beyond that.

Proper Two Kingdoms may see support lent to Trump as a lesser of evils, but that support would be accompanied by sustained and frank condemnation of his personal conduct, leaving the Don in no doubt that he was an unrepentant sinner in desperate need of spiritual regeneration.

It’s reasonable that people should try to get their churches to endorse gay and lesbian sexuality (and plenty of churches these days do), because in trying to find examples of how holiness got soiled, Paul wrote from within an intensely religious culture that was hostile to man-man sex. That view was cultural and, unlike more obvious and incontestable things like greed, we now see Paul’s view on gay sexuality as prejudiced.

It was understandable in his time and religious culture. That doesn’t mean that prejudice should be perpetuated.

It is not that shocking that people should want the church to stop vilifying gay and lesbian sexuality, considering the harm that vilification can do, and has done, for so many years.

Christians in more and more churches want their churches to endorse gay and lesbian sexuality because it is tender, loving, devoted, beautiful, pure, precious, lovely, costly, sacrificial – and a model of the fidelity that is of the very nature of God.

I find it very sad that Christianity – in this day and age – is used as a mandate and platform for bigotry and prejudice.

I don’t think Sanders’ ‘ethical reasoning’ in this context is weak at all.

I’d argue he just confronts your paradigms. The justice and the conscience of the matter stands, on its own grounds, in pure reason of what is decent, good, and faithful.

And even many conservatives accept a version of the cultural argument when it comes to slavery and divorce (usually involving an “arc of meaning” and “direction of travel” across the whole of scripture). Even allowing for the doctrine of biblical authority, I don’t see why this direction of travel must arbitrarily cease at the closing of the canon.

Yes, granted, scripture is uniformly negative about homosexuality in a way that it isn’t about liberating slaves or empowering women. But allowing for progress within the canon sets the precedent that parts of it can be wrong, and raises all kinds of awkward questions. What if there was zero chance of people embracing certain ideas prior to the fourth century A.D.? Should the church have left the canon open forever? Are we arguing that humanity had reached some state of perfection when it was closed?

If not, then why can’t we progress further then we were at the Bible’s close? Implicitly, we accept this. Christians widely accept that, say, democracy’s a good thing, and many would reject Paul’s injunction to obey civil governments, however tyrannical. Sauce for the goose …

James, when you said “And even many conservatives accept a version of the cultural argument when it comes to slavery and divorce…”

That’s not really true is it?

Jesus in the Gospels says that divorce was allowed by Moses (not God, but Moses) because the Israelites were hard-hearted. So if we follow Jesus Christ as Christians do (the clue is in the name, “Christian”) then we tolerate divorce exactly the same as Jesus Christ did.

St Paul’s letter to Philemon is about slavery and is clearly telling the slave owner to accept the former slave back as a brother, i.e. an equal. That letter is in the New Testament precisely because it is a letter for everyone even now. If some society makes someone a slave that person is still our equal and is still valued by God – the issue is more with that society, than with Christians.

Without doing a redux of the recent epic slavery discussion, yes, Paul says that Philemon should treat Onesimus as a brother, but (if he was a slave, some scholars dispute it), doesn’t order his release. Recognizing the inherent human worth of slaves was mainstream Stoic thinking, radical, but well inside the 1st century Overton Window. (Indeed, it led to sweeping legal reforms within the Empire.) In c.7 of 1 Corinthians, Paul enjoins slaves to be content with their lot.

As for Jesus and divorce, his more exacting ethic is either no divorce (Mark) or no divorce with a narrow exception for adultery (Matthew). Not being in any kinda position of power within 2nd Temple Judaism, he had no choice but to tolerate it, but it certainly wasn’t his teaching.

James, I agree to some extent with you on this (and I don’t think I engaged enough on the thread on the slavery post).

I think it is useful to read e.g. Seneca’s views on slaves in Letter 47 https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Moral_letters_to_Lucilius/Letter_47

and there are some observations in common with Paul. But Paul’s views are clearly more radical: to treat slaves ‘with equality’ because we are all slaves of Christ is to go further, and is rooted in an anthropology where all, slave and free, are made in the image of God.

I am not sure I understand the idea that the ‘ethical’ thing to do would have been to demand manumission; this would have led masters with no-one to do necessary work, and slaves with no income, home or security.

Manumission wouldn’t have obliged ex-masters to cast ex-slaves onto the street: as the liberated slave’s patron, they could employ and house freedmen until they wanted to leave. Indeed, it was customary for liberti to become part of the paterfamilias‘s extended family, and Roman society took a dim view of abusing manumission to offload sick or elderly slaves. Several Stoic reforms to slavery laws addressed this (i.e., allowing the state to forcibly buy slaves from neglectful masters, automatically liberating abandoned slaves, etc).

By any ethical code worth the name, Paul’s instructions to the flock ought to’ve been clear: unqualified condemnation of slavery as the gravest of sins, and a command that all Christian masters liberate and compensate their slaves forthwith (or, in cases where Roman law had started to set limits on manumission, to treat their slaves as free until such time as they could be officially liberated). But hey, I don’t blame Paul for not being that far ahead of his time, and always view the epistles in their historical context.

But you too are speaking from a specific cultural context Susannah, and yet you assume yours to be morally superior to Paul’s; why is that? Do years passing mean that we automatically become better people?

Your view of sexuality is one example of this. Paul’s view is clearly linked to creation ordinances, to the bounds in which sexual activity is to be safely enjoyed. Where does your idea of a “sexuality” that needs to be celebrated come from? Some churches have tried to “reclaim sexuality for God” – with predictably disastrous consequences.

I’m presuming from your post that you also welcome polyamory at the altar? If not, on what basis? Also, incest, given that we have the technology to ensure no genetically impaired offspring might result?

Marcus,

I believe that God has given us consciences and that we are expected to use those consciences to make our moral choices and best attempts to live decent lives. I believe a gay couple or a lesbian couple, caring for each other, sacrificing for each other, expressing love intimately and in day to day commitment, and living lives of fidelity, is an example of decent life.

My view is shared by many other people, both inside or outside the church.

Furthermore, like many others, I believe that when we read the bible, we should take social and cultural context into account. None of this is new. You are well aware, I am sure, that the Church of England harbours both views like mine and maybe views like your (which I don’t claim to fully know).

I am making a case, specifically, for no longer vilifying sexual love between people of the same sex. I have not mentioned polyamory or incest, mainly because I have no experience of them.

I’ll leave that to others to debate. My belief is that for every issue in life, we need to exercise our God-given consciences to try to do what we believe is right. There are many issues not even mentioned in the bible, where we need to do this.

As for Paul, yes, I think he’s pretty clear in his opposition to man-man sex, and that’s what I’d expect from the religious culture and assumptions that existed at that time. Do I think his prejudice should be perpetuated for all time? No I do not. Nor do many other Christians, who get that he was writing in the culture of his time, and drawing on creation narratives to justify his worldview.

Doing just that, he uses the creation narrative elsewhere to mandate female submission – justifying his view “because Eve sinned first”. Eve didn’t even exist. Most Christians in the Church of England would accept that Eve was a mythical character, that Adam had ancestors because humans evolved from earlier species, and yet… Paul justifies female subordination (in some cases) on the mythical actions of a mythical character.

Paul lives in a religious culture and a society that was okay with men being the head over women, and with the idea that man-man sex was abomination that would send you to Hell.

Thankfully we don’t hold those views today, and neither should the Church. Nor would we tell slaves to submit to their masters. We would demand they are all set free.

Cultures and society change. Paul’s words reflect his time and culture. For our own time and culture, as Christians we are best to reflect prayerfully on each issue, and then exercise our God-given conscience.

Fundamentally, I believe that gay and lesbian sexuality is decent and lovely, and that gay and lesbian relationships can express fidelity as well as straight ones.

We can go over and over this, and not share the same views on the issue. This has been going on for 50 years or more in the Church of England. At some point we will have to agree to disagree, and maintain a ‘unity in diversity’ of conscience in this matter. I am willing to do that. I believe the true test out of all this is not winning the debate, but accepting difference and loving one another, praying for one another’s flourishing in our shared unity in Christ, which is the only, and eternal unity – a unity that runs deeper than institutional uniformity.

If you can suggest a better outcome that is practicable, I’d love to hear it. If you don’t agree with gay sex, don’t have sex with a man. But does that give you the right to dominate another Christian’s conscience on that matter, or the sincere convictions of probably half the membership of the Church of England who think you (and Paul) are wrong in relation to our communities today?

We are putting off so many young people who are frankly disgusted by the prejudice of a Church that vilifies the love and fidelity and intimacy of… their friends, their cousins, their uncles, sometimes their parents… and in some cases themselves.

We need a new paradigm to handle the Bible right. We are bringing disgrace on the Bible and the gospel by literalising Paul’s views as if all of them are infallible and applicable for all societies, in all times.

A lot of people are being put off the Christian message by this perpetuation of prejudice: at the very least, and I think the trajectory of the Church of England is going that way, those priests and church communities who believe in celebrating gay and lesbian commitment (including its intimacies) should be able to do so…

That is coming, I really believe, as it has come in Scotland. And if it does…

What will you do?

Why is the condemnation of same sex sex ‘cultural’ but none of the other behaviours in Paul’s ‘vice list’ cultural?

It seems you have arbitrarily assigned it as ‘cultural’ and by doing so can then dismiss it as irrelevant today. Seems very convenient.

The other behaviours are ‘cultural’ too…

But whereas greed is still culturally understood to be wrong, man-man sex no longer is.

Slavery was ‘cultural’ back then. Do you propose that I am arbitrary if I repudiate that too?

It’s not just ‘convenience’ to call out prejudice and injustice. God has given us conscience. And it’s not just me being ‘arbitrary’. Half the membership of the Church of England accepts gay relationships and does not think man-man sex is wrong. And an even higher proportion of the British public.

This is not ‘convenience’. It is simple decency.

Paul was prejudiced, but that was understandable, given the religious culture he lived in.

We are not obliged to perpetuate that prejudice.

So to confirm Susannah, if 50% or more of CofE members decided that Paul’s condemnation of greed was just cultural, and we wanted a ceremony to celebrate greed, you’d be fine with that? You’d be happy for newcomers to come to their first church service and hear the vicar blessing an investment banker’s latest statement, and wouldn’t raise any objections because you were happy that we were unified in diversity?

Ah so using your logic, if greed became ‘good’ in society’s cultural eyes then it is to be deemed good.

Is that really how you think Christians and the church should decide on right or wrong!

To Marcus and PC1,

I will only speak for myself. I believe that greed is wrong. What basis do I have for that. Do I base it on Paul? No. I may reflect that greed was wrong in his culture too. But the basis for my view that greed is wrong, is that I exercise my conscience.

This is what I’m advocating for gay sexuality too.

I think that Paul was right on one, and wrong on the other.

And if a majority today championed greed? I’d do the same again, I’d listen to my God-given conscience. And I would oppose their view.

I wouldn’t leave the Church over it. I don’t believe in schism. But they’d have to put up with my divergent view.

In reality, the majority of people in the Church of England will never believe greed is right, even though in personal terms many of us may be challenged in prayer of how we spend our money in a hungry and suffering world.

I think it’s best if we stick to sensible examples. God speaks to us today, through conscience, through people, and none of us are infallible. Neither were the authors of the Bible and neither is the Bible itself.

We have to pray, and listen to our conscience, and do the best we can. Because in listening to our consciences, we may be opening our hearts a bit more to the love and the grace of God.

I am a lesbian woman, married to my wife, and loved by our church community. I know first hand, as we all do, that love involves shared joy, shared cost, shared sorrow, shared sacrifice. But for many churches in the Church of England, a marriage like ours is seen as a gift and blessing to the community we share in. It is so lovely.

And I’d ask either of you: what possible harm does our intimate love do to you? Our fidelity to each other, or the fidelity we try to exercise in loving our neighbours? Our private sexuality? Are you harmed by us?

And I’d encourage you to try to co-exist, and possibly open your hearts and consciences to the test of love: is what somebody does (say greed, say sexual fidelity) loving?

Because love is the great commandment, and I believe God still speaks to us today, urging us to seek out the loving, the kindness, the fidelity.

Paul’s hostility to man-man sex reflects his own cultural views. As I’ve said above, I think his views are clear. However, he was not infallible, and we don’t have to perpetuate those cultural views forever and ever, when God speaks to our consciences and challenges us to open our minds to love.

We may never agree on this issue, but the test is can we love one another. Can we seek our unity in Christ, when we can’t find uniformity in our humanity? Can we eschew schism? Can we seek each other’s flourishing? Can we live out our Christian lives in maybe diverse communities and expressions in the Church of England, helping the elderly, comforting the distressed, supporting the poor, being servants in the best way we can, in our church communities and the communities up and down the land alongside which we live?

Through the opening up to love, if not to uniformity, can we serve in various and different ways, and be the Church of England?

Or do you choose to cut and run?

I really wouldn’t want you to. I’d want the Church to be precious in all its diverse consciences, if only we try to walk together in love, and recognise the primary call to love our neighbours – and community by community, in our different styles and emphases, try to do just that.

God bless you.

Susannah

But your conscience could be merely a cultural conscience? Given the importance of downgrading things that are merely cultural, that ought to be significant.

How do we investigate whether or not it is. By the fact that all of a sudden consciences are telling people that things are ok that were not thought to be ok, and (by coincidence?) just at the time when the media are saying the same.

That cannot possibly be a biological conscience then. It can only be a cultural conscience, with the downgrade in importance that that entails.

I didn’t marry my wife out of “cultural conscience”, Christopher.

I married her because I love her.

I didn’t marry my wife out of “cultural conscience”, Christopher.

That wasn’t the question.

Paul’s conscience told him that same-sex activity was wrong.

Yours tells you that it is okay.

You think Paul’s conscience was wrong because it was infleuenced by his culture, and therefore can be ignored.

But — isn’t your conscience also influenced by your culture?

So if you’re going to ignore Paul’s conscience because it is influenced by his culture, shouldn’t you equally ignore yours because it’s influenced by your culture?

We should never ignore our consciences.

But to repeat, I married my wife out of love, not because it was culturally acceptable (which it is).

I would have married my wife even if the punishment for marrying her was stoning, or being thrown off a rooftop by ISIS, or vilified by other religious people.

Culture changes, sometimes for the better, sometimes for the worse. People have to discern which it is. Overwhelmingly people in the UK, and many Christians in the Church of England, believe in good conscience that gay sexuality is fine.

If *everyone* is influenced by their cultures, as you argue, then it is quite possible Paul was too, and then we’re left in a situation where we have to listen to our consciences (which are God-given) and take responsibility.

S, you know this debate never ends, because quite simply two large groups of Christians take contrary positions of conscience.]

Therefore what other resolution can there be, within the Church of England, than to acknowledge both sets of beliefs, and go big on love in all other areas of our Christian service, and especially in our love for one another?

We can have ‘unity in diversity’ and both groups can carry on going to church each week, serving their communities each week, and living and acting according to their consciences.

The other options are tyranny or schism.

S, you know this debate never ends, because quite simply two large groups of Christians take contrary positions of conscience.

But this is precisely why the debate should not be about conscience, but about logic applied to the evidence of Scripture.

We can have ‘unity in diversity’ and both groups can carry on going to church each week, serving their communities each week, and living and acting according to their consciences.

But that would be a dishonest unity built on ‘constructive ambiguity’, where you find a form of words that both sides can sign up to only because they mean totally different things by them. At a fundamental level, every time the Bible was read, half the congregation would be listening to something completely opposite to the other half.

That’s not unity. That’s pretend unity. It’s hypocrisy, it’s basically a lie.

I don’t think Paul’s unclear. I don’t think it’s confusing. I don’t think it’s complicated.

In the religiously intense culture and circles Paul (and earlier writers in the OT) lived in, the view of man-man sex was a negative one.

That was their problem. It shouldn’t be ours.

We should not perpetuate their prejudice.

Also, yet another article on sex. It’s like some Christians are obsessed by the subject.

In terms of simple implementation, this: if you’re a guy who doesn’t like man-man sex, find a woman.

But please stop policing everyone else’s privacy, tenderness, fidelity, sacrifice, love.

There is a world of pitiful poverty, deprivation, abandonment, suffering out there. In fact it’s on our doorsteps. Maybe we should obsess less about people’s private love, and obsess a bit more about the tangible suffering in our world.

And we wonder why young people are alienated from the Church…?

To return to your question, Ian, NO… I don’t think Paul was unclear. But I don’t think Paul has the final word. He was closed, it seems, to the loveliness and tenderness of gay and lesbian couples, certainly as we see them flourishing in our society today, bringing blessing and gift to community. That was his loss.

The Word of God is not the literal verbatim views of the Bible authors. They are fallible, like all humans are, and they wrote from within their own cultures. Is Paul unclear? I don’t think that’s the right or most relevant question to ask. Is Paul wrong about man-man sex?

I think most people would say he is.

And they could be right to say so. They could be right, and Paul could be wrong. The real Word of God – the actual person of God who calls us into being and becoming, can open our hearts to that amazing flow of love as we read the Bible (and indeed when we read other books). This God is like water flowing through a conduit. And the Bible is a conduit: the expressions and attempts of fallible human beings to make sense of mystery, trying to comprehend and communicate profound encounters, yet fallible, limited, like we all are.

The Word of God is not the Bible. The Word of God is a person. And through God’s Spirit, we may find grace to experience our own encounters, to open our hearts and minds, to receive grace, to become (fallible) conduits ourselves for love.

Revelation does not end with the written Bible. Revelation is emergent, generation by generation, community by community, and it hinges on the interaction of our God-given consciences with the Person of the Holy Spirit, and our encounter with Jesus.

Paul was trying to make sense of the importance of holiness, writing in the terms and ideas of his own culture, and what they felt was pure and impure. His words get filtered through the very religious community he was living in, and the culture and assumptions of the day.

I have said before, I think the Bible is negative about man-man sex. I think Paul seems to have been consistent with those cultural convictions or prejudices.

But we’re reading the Bible in the wrong way, if we try to attribute inerrant wisdom to Paul. He may well have been ‘clear’. He may also be clearly wrong.

We need a new paradigm.

A new default way of reading and understanding the Bible: recognising the fallibility and limitations/contexts of the authors. And trying to see past the cultural ephemera to the profundity of what they were trying to express.

What was he really talking about? He was talking about holiness. Was he qualified to talk about diverse sexuality as we understand it more today? Probably not.

Are Christians who take him literally? I’m not sure they are either. They present a real danger to gay and lesbian young people, by vilifying this lovely, beautiful, precious aspect of who many of them are. Young people need to be protected from the prejudices of Paul. They need to be told that was just Paul’s time and culture. They need to be affirmed in their sexuality, as they explore it for themselves. They need to be told about the love of God, and the person of Jesus, and how God is far cooler than Paul, and speaks to us NOW… in our lives, in the lives of our friends, who may be gay themselves, even if we are straight.

The majority of young people are also ‘clear’ today: gay sex is not wrong. I agree with them, not Paul. And I say that because of who God seems to be, and because of the interplay of Spirit and conscience, experience and prayer, compassion and the joy that gay people bring to my church and my community.

“That was their problem. It shouldn’t be ours.” Succinctly put, Susannah, and exactly my position on this.

Liberals would benefit no end from ditching the ceaseless debates about reinterpreting Paul. Not only are they exhausting for all parties, but they inspire few (if any), and arguing about what he meant shuts off all debate about its merits. I don’t care if Paul said it: why should I believe it? If that answer’s rooted in an argument from authority, no liberal should give it the time of day.

So long as this is an argument about biblical interpretation, it’s an argument on conservative terms, an argument that implicitly surrenders to conservative theology, and an argument that’s doomed to failure as a result. Liberals needlessly deny themselves their strongest rhetorical weapon: Paul was wrong. The second those underlying terms are themselves challenged, all bets are off.

‘Also, yet another article on sex. It’s like some Christians are obsessed by the subject.’ If so, it is not me. at least 89% of may articles are on others subjects. Yet in the C of E we continue to be faced with a relentless campaign by those who want to see change, and from time to time it is appropriate to offer a response.

And you then comment: ‘That was their problem. It shouldn’t be ours. We should not perpetuate their prejudice.’ This is the point of difference. The Church of England sees the Jesus of the gospels and the canonical writings of Paul as expressing the ‘word of God written’. So far from it being a prejudice, it discloses God’s will to us.

Hi Ian,

Thank you for your response. You write: “a relentless campaign by those who want to see change”… do you mean a bit like those pesky black Americans who wanted to see change?

And when you say “by those who want to see change”, you do of course realise that “those who want to see change” is actually a majority of people in the Church of England these days. The public, including the majority of people in the pews, no longer believe gay sexuality is sin or abomination, but rather they have come to recognise that gay sexuality is worth celebrating and affirming.

When you refer to “the Church of England” you seem to gloss over the reality that half the Church of England reads the Bible in one way (which ends up condemning gay sex), and half the same Church reads it a different way (and want to accept gay sex).

It’s not as if it’s some sect of misfits, an irritant minority, the gays, with their gay agenda. It’s that half (or more) of the Church of England who have no problem with their uncle or daughter having intimate same-sex relationships… in fact it’s so reasonable and accepted in our country that they treat it like other relatives who are in heterosexual relationships.

This could all be resolved if we implemented ‘unity in diversity’, acknowledging what is already the reality in the Church of England – diverse conscientious views… and then getting on with all the other aspects of loving one another, and serving our communities. The real difficulty arises when an attempt is made to dominate sincere and faithful consciences, and impose just one view on everyone else. Or when discontented clerics raise petitions because they object to bishops giving parishes options over transition recognition in church.

The problem is the attempt to impose one view on everyone. That’s not going to hold in the Church of England, is it? The trajectory, as I suspect you well know, is towards unity in diversity along the Scottish model.

And then perhaps we can get on with all the rest of spirituality, because freedom of conscience will have been defended.

Now, if that ‘unity in diversity’ was introduced in the Church of England (as it very well may be in the future) what will you do? Will you schism (which I’d hate) or will you hold fast to your own understanding of scripture, and accept that others will hold firm to theirs, and journey on together as we finally move forward to focus far more on the dire social and pastoral needs of so many of our communities.

To recap: “The Church of England sees…” masks the reality of the Church of England today, which is that it actually “sees in various and frequently divergent ways”.

Our polity needs to reflect that, because the other way is theological domination, and on the ground that is just regarded as risible.

Beyond the Church of England, in the eyes of the public and especially young people, this vague “Word of God written” assertion (what does it even mean, in specifics) just alienates, because it contorts decent social understandings of intimate love and sexuality, and most people can’t take it seriously any longer.

If you don’t agree with gay sex, don’t have gay sex. That’s pretty simple.

But don’t assume to impose your convictions on everyone else, whether in the Church of England or outside it. Unity in Diversity respects the conscientious differences of belief we have. You’ll find people are a bit less relentless, once there is at least that recognition that we are a Church with various views and not just one.

Ian, I’m debating, not trying to be hostile. I respect your own conscience on these matters. I’d be glad if you could respect the conscience of so many people today in this Church whose conscience is different to your own.

At the personal level, I really do wish you well, and the flourishing of your Christian life and community. Grace be with you.

Actually Susannah, when you wrote:

“….And when you say “by those who want to see change”, you do of course realise that “those who want to see change” is actually a majority of people in the Church of England these days….”

They are NOT actually a majority in the Church as I have seen at a number of conferences in which lay people have outnumbered clergy, making the conference or event a real success, and show that the ordinary Church member in the pew is, and are, truly fed up with clergy walking away from Christianity.

Your idea that those in favour of SSM are a majority is a total fiction.

Dear Susannah,

When you open by writing:

“… do you mean a bit like those pesky black Americans who wanted to see change?”

No Ian did NOT say anything about Black americans, or black people generally, nor did he even allude to anything like that.