Occasional contributor to the blog, Dr Richard Briggs (Cranmer Hall, Durham) has just published a new book that is a little different from his usual style. Intrigued, I was able to ask him about it.

IP: Richard, you’ve written a book of poetry!

RB: Yes I have. It’s called Not of this Worldview, and it is published this week by Sacristy Press, who are based here in Durham where I live.

IP: What is it about?

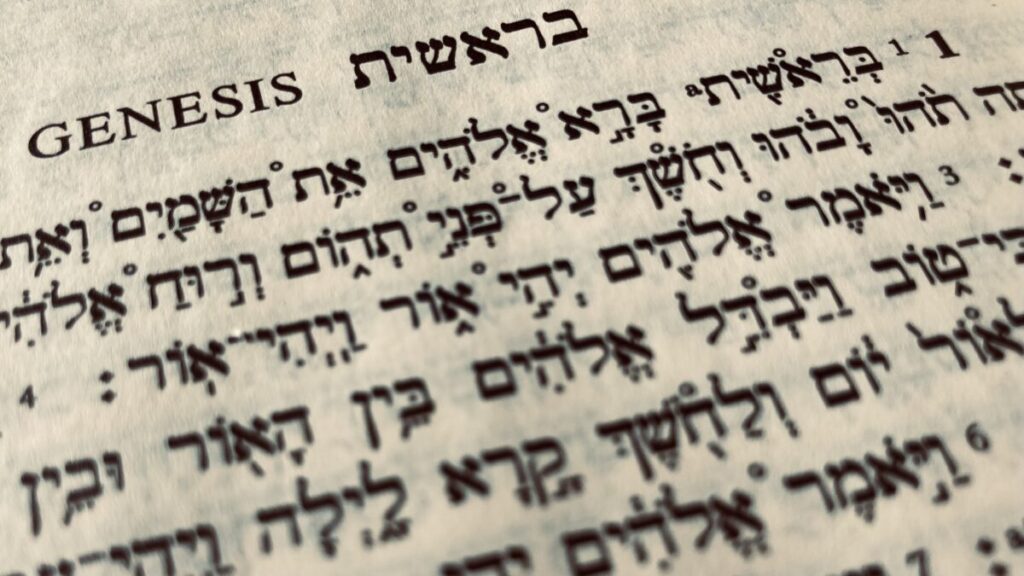

RB: Many things! First, it is about seeing the world as God would have us see it. I have sometimes used that as my working definition of wisdom – the kind of wisdom we find in Proverbs or James for example – where the ‘gift of eyes to see’ (compare Prov 20:12) is about clear-sightedness regarding God’s perspective on the world around us. One of the first poems in the book is in fact called ‘The Gift of Eyes to See’, and reflects on the Proverbs and James dynamic. Other poems explicitly retell parts of scripture in freshly seen ways – a pair of them recast Genesis 1 and Genesis 2 as very different texts. The first of them begins:

God begins: it’s heaven-and-earth time.

Well the earth was like a wishy-washy mish-mash

And there above the deepest darkest deep

The Spirit-God / the breath of God / the wind of God

Was hushing all the wildness to sleep…

It is based on a careful reading of the text (using William Brown’s idea of translating tohu wabohu in Gen 1:2 onomatopoeically as ‘mish-mash’, for example), but it is striking out to be creative and give us new ways of seeing familiar truths.

Secondly, it is about noticing the ways that God’s kingdom is at work among us. I like the idea that the ‘kingdom of God’ is the work of God among us – the rule and reign of God as various studies have shown us. I draw especially from Luke 17:21 – the kingdom is right here among us as God’s people on earth. So some of the poems are about seeing glimpses of God on the move, whether impressively or subtly, comprehensively or covertly. A poem about Durham Cathedral is followed by one about my struggling local parish church in the ex-mining village of Sherburn where I was associate minister. God is to be found in both, but in very different registers.

Thirdly, I would add, it is about a little of the joy that can be found along the way with God. Some poems celebrate moments of grace amidst stress and turmoil. Some circle around a funny incident or an entertaining insight. There is a series that imagines John the Baptist at a speaking tour of England – speaking at the student event, the local big church, the mothers’ union. Another one imagines Pharaoh pondering Brexit and Moses replying as the people make their way out.

I could go on, but might add one more aspect: in an autobiographical and reflective poem that closes the book I look back on my journey through life thus far as a Christian. I called it ‘Portrait of the Zealot as an Old Man’, and it casts an eye back on a road I would characterise as taking me from zeal towards wisdom … not that I have already attained great wisdom, you understand. I was happy to find a way of striking a balance that appreciated both in their way: the penultimate verse reflects that ‘I would not be here now/without the kick-start …’ and the final verse then turns and says ‘And I am not there now/where it all began …’ Both make their contribution. Several of the poems chart some of this journey from zeal towards wisdom.

IP: Some of us will know you from your theological writing and also your editing of Grove Books’ biblical series. We didn’t know you wrote poetry as well…?

RB: I’ve been writing poetry for years, on and off. I like that it is a very different discipline with words. Theological writing piles up the pages until a point is made or a question conquered, and yes I do a lot of that. But with a poem sometimes less is more – it is about getting the right words in the right place to cast an image or suggest an idea.

IP: You once said that ‘A good poem is like a picture on a wall.’ What do you mean by that?

RB: I love art galleries. But I have never been good at hanging pictures around the house. I am not speaking of my practical difficulties with that most complex of tools – a hammer, or the intricacies of banging a nail into a wall, which frequently defeats me. No, the issue has always been situating the picture properly in relationship to other pictures, windows, furniture, the size and lighting of the room, and so forth. In other words: much of what makes a picture work for the viewer is the context that allows it to be seen well. The words of poetry, it seems to me, are a bit like that. Where prose pours forth, poetry hangs back, lets the space around the words be as significant as the words themselves, and then hangs its points – its picture – elegantly on the wall.

IP: So how in practice do you go about writing a poem?

RB: Poetry is about economy of expression. See clearly and say briefly. The seeing may relate to an idea, a place, an experience, an image, or even a person. Then let initial word-images come to mind that capture an angle on that idea or experience. There is no way to force that initial expression.

I then find that once a line or two has come to mind, the structure (or lack of structure) of the poem is set. If rhyming and scanning come in at the beginning, then I need to carry them through. If they do not then the poem unwinds in its own free-form way. Some of the poems in the book are really tightly structured – I enjoyed writing a sonnet in iambic pentameter, and even tried a villanelle after my daughter introduced them to me from her English degree – but others are not at all structured.

IP: What made you turn from writing an occasional poem to producing a book of poems now? Was there a particular inspiration for that?

RB: Yes, two things in particular served to spark the book into being.

One was a wonderful conference at Durham’s Ushaw College called New Song: Biblical Hebrew Poetry as Jewish and Christian Scripture for the 21st Century in the summer of 2019. It was the first time I had attended a poetry reading; the first time I had chatted to ‘working poets’; and the first time in years that I had thought seriously about writing or publishing poetry myself. I am co-editing the papers from the conference, forthcoming from Lexham Press, and we are including contemporary poems among the responses. It all felt life-giving, and made me ask whether I should be going further with my own poetic interests.

Then, secondly, as you and some of your readers will know, I became very ill. I spent several months in 2020 undergoing medical treatment, spending two or three weeks in hospital, and having to recuperate for a long period afterwards. I had whole days where I … did nothing. It was like being spiritually re-booted. I would not want to undergo the illness again, but the ensuing time of recovery came with many unexpected blessings. I did not jump straight back into writing the theological books and papers that normally keep me busy. Instead I found myself dozing in bed in the afternoon, and pondering some of the strange ways that I was seeing things from fresh angles in a season of enforced rest.

Then, secondly, as you and some of your readers will know, I became very ill. I spent several months in 2020 undergoing medical treatment, spending two or three weeks in hospital, and having to recuperate for a long period afterwards. I had whole days where I … did nothing. It was like being spiritually re-booted. I would not want to undergo the illness again, but the ensuing time of recovery came with many unexpected blessings. I did not jump straight back into writing the theological books and papers that normally keep me busy. Instead I found myself dozing in bed in the afternoon, and pondering some of the strange ways that I was seeing things from fresh angles in a season of enforced rest.

And suddenly it was poetry that came pouring out.

Many years of unprocessed experiences and feelings clamoured for attention – with a few words here, an image there, an amusing rhyme that highlighted an emotion, an understated comparison that made several points at once. I began to look forward to afternoons with a bed and a notepad, not forcing the writing but letting it voice some of the extraordinary mystery of being alive in God’s world, on good days and bad (of which I had a fresh stock of experiences to draw from).

Gradually, slowly, I realised I was finally hanging pictures on the wall – poems that settle into their own expansive space on the page, and say ‘Look at it like this!’ or ‘Stop, breathe deeply, and notice!’ So by this unexpected route I finally came to the opening of my much delayed ‘poetic exhibition’. I hope readers will enjoy browsing around the gallery; lingering, or moving on. And if readers start to notice some of the same shadings and surprises that I have noticed as I make my way through God’s ever-creative kingdom, then I shall be happy.

IP: That sounds very interesting, and I look forward to reading it. What else are you working on at the moment?

RB: I have a book coming out on Psalm 23 later this year, from Baker Academic, as part of a new series on key scriptural texts. This ties in to a theology of the book of Psalms that I am also writing for the Cambridge series on the theology of individual biblical books. And there are a range of other things in progress too. Who knows, perhaps more poetry too.

IP: Thank you for taking the time to share these fascinating reflections.

Richard S. Briggs is Lecturer in Old Testament and Director of Biblical Studies at Cranmer Hall, St John’s College, Durham and the Prior of the Community of St Cuthbert based at St Nic’s Church in Durham marketplace. He is also an occasional contributor to Psephizo.

Richard S. Briggs is Lecturer in Old Testament and Director of Biblical Studies at Cranmer Hall, St John’s College, Durham and the Prior of the Community of St Cuthbert based at St Nic’s Church in Durham marketplace. He is also an occasional contributor to Psephizo.

Note: Some parts of some answers here appeared previously at the Sacristy Press website and are adapted here by permission.