This article was printed in the Winter edition of New Wine magazine, and is reproduced here by permission.

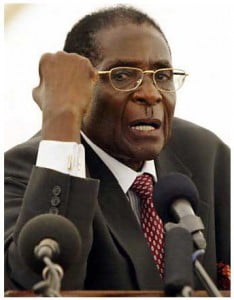

We are confronted almost daily with the reality of evil people at large in our world. Robert Mugabe is the latest in the long line of villainous leaders to dominate headlines. President of Zimbabwe since 1980, he has inflicted untold misery on his people—so why has he been allowed to continue? It is striking that Western policy in recent years has often appeared to be shaped by response to individuals, evil leaders who need to be toppled. So the second Gulf War in Iraq was directed specifically against the regime of Saddam Hussein. And it was seen to be a triumph of Western action that Gaddafi was deposed as leader of Libya. However evil certain systems or cultures appear to be, it is evil people that we feel the need to focus on.

We are confronted almost daily with the reality of evil people at large in our world. Robert Mugabe is the latest in the long line of villainous leaders to dominate headlines. President of Zimbabwe since 1980, he has inflicted untold misery on his people—so why has he been allowed to continue? It is striking that Western policy in recent years has often appeared to be shaped by response to individuals, evil leaders who need to be toppled. So the second Gulf War in Iraq was directed specifically against the regime of Saddam Hussein. And it was seen to be a triumph of Western action that Gaddafi was deposed as leader of Libya. However evil certain systems or cultures appear to be, it is evil people that we feel the need to focus on.

Questions in Scripture

Scripture appears similarly to be concerned with evil individuals, and the challenge they offer to our understanding of God’s love and power. What will God’s response be to evil and obstinate Pharoah, oppressing and enslaving God’s people? asks the writer of Exodus. What will God do about a succession of kings of Israel and Judah who ‘do evil in the sight of the Lord’? asks the writer of 1 and 2 Kings. How can God not only allow the foreign leader Cyrus to flourish, but actually make use of him in liberating his people? asks Isaiah. What sense can we make of the tyrannical kings Nebuchadnezzar, Belshazzar and Darius as we face tyranny in our own day? asks Daniel. The questions continue to haunt us.

In an extended reflection on this question, the Davidic Psalm 37 starts with the injunction ‘Do not fret because of the wicked’, a call to let go of the anxiety we feel at the evil we see around us. But perhaps in the West that is not our real problem. The real challenge is to feel concern about evil more deeply; most of our experience is at arm’s length, as we are presented on television or the internet with bite-sized packages of evil, often simplified and made neat and tidy. This edited evil is easy to boo, and it is also clear who we ought to cheer on as the champions of goodness and freedom. And this touches on a key issue.

Never mind the figureheads—what about the henchmen? For every Mugabe or Gaddafi, there are hundreds, possibly thousands around them who have supported them and helped them gain and retain the power they now misuse. Hitler was, in the 1930s, regarded as a national hero by many, saving Germany from the ignominy of humiliation by the Allied powers. And those ‘many’ included much of the Church, including at first Dietrich Bonhoeffer, even though he is better known for his later change of mind. The challenge of the evil person is a test of our eyesight; it is easy to see evil at a distance, but how good are we at spotting it close at hand?

One of the most challenging books on my shelves is Christopher Browning’s Ordinary Men. It tells the story of a reserve battalion in Poland in World War II, and introduces us to cheerful, friendly, ordinary men who killed without hesitation or apparent remorse for years on end, in docile obedience to an authority they happily accepted as legitimate. As such it is a chilling reminder of what we as humans are capable of when we insulate ourselves from the reality of evil on our doorstep.

If we are expecting God to stop the ‘big people’ doing evil, why don’t we want him to stop the ‘small people’ doing evil? How evil do we need to be for God to intervene? What would life look like if God prevented all my evil thoughts and actions?

There is a cartoon doing the rounds on the internet at the moment, with the following saying: ‘I wanted to ask God why there was so much evil in the world, when he could do something to prevent it. But I was afraid that he would ask me the same question.’

Speaking Truth to Power?

Last week I attended a conference on biblical studies in San Francisco. It is an annual gathering of the world’s leading scholars, and there were some fascinating papers on a whole range of important issues. But the image I will remember most is that of the homeless, begging on almost every street corner, often representing lives wrecked by poverty, drink and drugs. One woman, her face covered with sores, was simply unable to take part in any kind of coherent conversation. I was challenged about my immediate response to the plight of such people—but I was even more challenged by the bigger question: was I prepared to give up all the things I enjoy from the systems we live by which creates these problems? The ‘free market’ system which has left these people destitute is also the system which allowed me to travel half way around the world and stay in a fabulous hotel. Am I prepared to protest against the evils of this system?

From my study in college I have a view of a beautiful blue cedar tree. Underneath it is a plaque showing it was planted in memory of Janai Luwum, who trained at St John’s when it was based in London, and eventually became Archbishop of Uganda. He was prepared to speak truth to power, in the form of Idi Amin, and he paid for it with his life. He was ready to oppose the people and systems of evil in his world.

From my study in college I have a view of a beautiful blue cedar tree. Underneath it is a plaque showing it was planted in memory of Janai Luwum, who trained at St John’s when it was based in London, and eventually became Archbishop of Uganda. He was prepared to speak truth to power, in the form of Idi Amin, and he paid for it with his life. He was ready to oppose the people and systems of evil in his world.

Future Hope and Present Action

Psalm 37 ends on a note of hope. The psalmist returns to see what has happened to the wicked, and they have been swept away in God’s judgement. ‘I have seen the wicked and ruthless flourishing like a luxuriant native tree, but they soon passed away and were no more; though I looked for them, they could not be found’ (vv 35–36). This phrase is picked up in Rev 12.8, where Satan and his angels no longer have a place, ‘because of the blood of the lamb’ (v 11). It is Jesus’ death and resurrection which marks victory over all forces of evil. It is a victory which we begin to know now, in our own lives, in our world as we follow his example of faithful witness, but which in the end we will only see when he comes again.

Why does God allow people to do evil? In the end it is a mystery. But it is a mystery that calls us to response by self-examination, by courageous action, and by hopeful anticipation that one day ‘He will wipe every tear from their eyes. There will be no more death or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away’ (Rev 21.4).

The article ends with important verses from Revelation. Rev. 12:8 says the place where Satan and his angels are no longer found is heaven, where in 12:11 our brothers (and sisters) can rest from the former accusations of Satan in heaven because they conquered him by the blood of the Lamb and by the word of their witness, for they loved not their lives even unto death. This faithful witness on earth is indeed based on the faithful witness of Jesus (the premier faithful witness, in Rev. 1:5, which also adds: and the ruler of the kings of the earth).

This rule over evil powers on earth comes to a head when the Lamb speaks his (final) wrath against “the kings of the earth and the great men and the generals and the rich and the strong, and every one, slave and free,” who were all loyal to the powers that be (Rev. 6:15-17). Yet before that final judgment, the faithful witness is illustrated well in Jesus’ words to Pilate in Jn. 18:36-37 (Jesus came into the world to bear witness to the truth; as the king sent from heaven, his kingship is not from the world and his servants remain loyal to him by not fighting, unlike those who support the kings of the earth).

After the Lamb is slaughtered by the kings of the earth, he then appears as the Lion king in heaven (Rev. 5:5-6). His death and resurrection, and the faithful witness unto death, are indeed the example for his servants to follow.