Lord Nigel Biggar is Regius Professor Emeritus of Moral Theology at the University of Oxford, and a well-known author on moral and ethical issues. He has just published Reparations: Slavery and the Tyranny of Imaginary Guilt (Swift, 2025), challenging the current narrative within and beyond the Church of England about the need for reparations for slavery. I had the chance to ask him about it.

IP: Why do you think the issues of reparations has become so important in recent years? What has sparked your interest in this issue?

NB: The topic of reparations for slavery is a distillation of the larger topic of ‘colonialism’. I first became interested in that issue during the 2014 referendum on Scottish independence. As an Anglo-Scot, I had a unionist dog in the fight and was viscerally opposed to the disintegration of the United Kingdom, which, according to the then British ambassador to the UN “would have had a devastating impact on the UK’s standing in the world, much greater than withdrawal from the EU ever would”.

Nevertheless, as a Christian, I could not regard the UK as divine. Nations and states come and ago. Before 1800 the United Kingdom did not exist. In the 1860s the United States almost ceased to exist. In 1993 Czechoslovakia did cease to exist. It was possible, therefore, that the Scottish nationalists were right and that the UK had come to the end of its justifiable shelf-life. So I felt morally obliged to consider nationalist arguments. And one I came across amounted to this equation: Britain equals Empire equals Evil. Therefore, Scotland needs to repudiate Britain’s bloodstained imperial past and sail off into a bright, new, shiny, sin-free future.

Yet, having read about the history of the British Empire for more than two decades, I knew that the simple equation, Empire equals Evil, is not historically tenable. But that was when I realised that colonial history was being used—and abused—for political purposes that I regarded as destructive. And I thought that someone needed to correct the distorted record—which I have sought to do in my 2023 book, Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning. I did actually broach the issue of British reparations for slavery there, but my latest book, Reparations: Slavery and the Tyranny of Imaginary Guilt is a much fuller treatment of the issue.

Why has the issue of reparations for slavery two centuries ago risen up the political agenda in recent years? The reasons are several. The immediate cause was the killing of the African American, George Floyd, by a policeman in Minneapolis in May 2020. This fueled a major upsurge in the US of the Black Lives Matter movement (BLM), which had emerged in 2014 as an informal alliance of people concerned to combat anti-racism in general, and specifically police violence toward black people in particular.

The BLM cause quickly crossed the Atlantic, where it was eagerly taken up by anti-racist groups who used it to promote the narrative that the UK, like the US, is systemically racist and that this systemic racism is rooted in historic British slave-trading and slavery. The causal connection between the 18th century and the present is ‘colonialism’, which the British—allegedly—continue to venerate. Therefore, in order to exorcise themselves of racism, the argument goes, the British must repudiate their colonial past, which can be summed up in one word: slavery.

The second cause of the present topicality of British slavery is exploiting the first but is somewhat older. In 2013 CARICOM—the Caribbean Community of fifteen member states and five associates—established a Reparations Commission to press the case for reparatory justice against former European colonial rulers such as Britain for “native genocide and slavery”. The case for reparations acquired a measure of apparent financial precision with the publication of the ‘Brattle’ report in June 2023, which calculated Britain’s debt as £18 trillion.

The Caribbean campaign for reparations is one expression of the third, more general cause, namely, a growing, worldwide assertiveness on the part of formerly colonised indigenous peoples. While this can be traced back to the League of Nations in the 1920s, it began to gather steam through the United Nations in the post-1945 period, finding focus in the 2007 UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

IP: I am sure everyone would agree that slavery is an appalling evil. How widespread has it been historically, and how significant was the Atlantic slave trade in that?

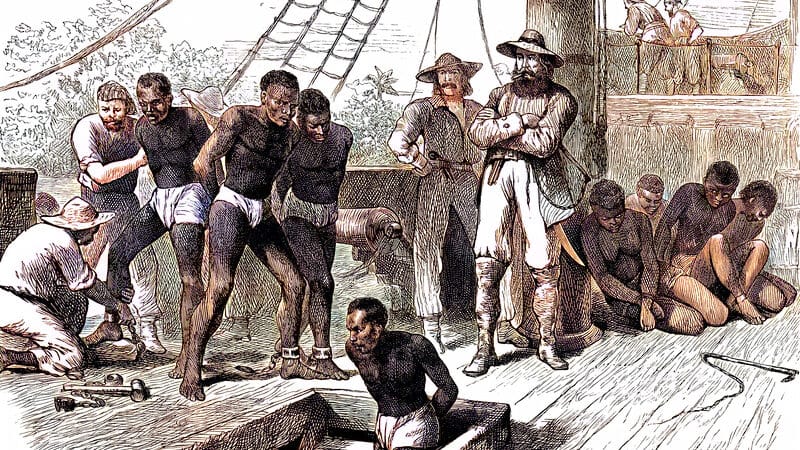

NB: One of the several contexts of the British enslavement of Africans between, roughly, 1650 and the early 1800s, that reparations-advocates invariably obscure is slavery’s historical universality. Across the globe societies employed slave labour in agriculture, mining, public works and even as troops. All the ancient Mesopotamian civilisations practised slavery in one form or another, starting with Egypt in the third millennium bc. To the west, around the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, the ancient Greeks, Carthaginians and Romans followed. To the east, slavery could be found among the Chinese from at least the seventh century AD, and subsequently among the Japanese and Koreans. In the Americas, the peoples of the Pacific North-West practised it from before the sixth century AD, the Incas and the Aztecs extracted forced labour from subject peoples from the fifteenth century, and the Comanches “built the largest slave economy” in what is now the south-west of the US from the eighteenth century.

From the time of Muhammad in the 600s onward, slavery was practised throughout the Islamic world. In the eighth and ninth centuries the Vikings supplied slave markets in Arab Spain and Egypt with slaves—again, white slaves—from eastern Europe and the British Isles. In the 1600s corsairs or pirates from the Barbary Coast of North Africa raided English merchant ships, and even villages in Cornwall and west Cork, for slaves. One estimate has it that raiders from Tunis, Algiers and Tripoli alone enslaved between 1 million and 1.25 million Europeans from the beginning of the sixteenth century to the middle of the eighteenth century. Another estimate reckons that the Muslim slave trade as a whole, which lasted until 1920, transported about 17 million slaves, mostly African, exceeding by a considerable margin the approximately 11 million shipped by Europeans across the Atlantic.

IP: Part of the challenge with reading the history of the Atlantic slave trade is locating in its historical context, particularly in the context of the conditions of ordinary men and women of the time. What difference does that make to the argument?

NB: There is no doubt that European enslavement of Africans in the sugar plantations of the West Indies was typically very brutal indeed, and it horrifies us. It is also true that other forms of slavery—such as domestic slavery in the Muslim world—was often less brutal.

That said, we need to put the horrors of British slavery in context. Enslaved African boys were often brought to the Arab world to serve as eunuchs. To that end, they had their genitals forcibly removed with a razor and the resultant wound cauterized by boiling oil. Nine out of ten of them died in the process.

And while urban workers in early industrial England were not slaves, because they had legal rights, their conditions of work and living were often quite appalling. They died young and in droves.

What difference does this make to the argument? It reminds us that life in the past—even in the quite recent past—was often ‘nasty, short, and brutish’. It reminds us that inhumane treatment was widespread and not at all confined to Europe or to formal slaves. And it reminds us that history contains an ocean of injustice, which is beyond human rectification. We are not gods; we cannot raise the murdered dead. Our instinctive desire for justice is one of the main fuels for belief in a God who can.

IP: It has been claimed that the slave trade was of great economic significance to the growth and economic development of the West, and therefore is of unique historic importance. Is that a fair claim, and has that been contested?

NB: A 2023 document sanctioned by the Church Commissioners for England, the body responsible for managing the Church of England’s assets, claims that profits from slave-trading and slavery were “central” to Britain’s industrial prosperity. This takes its cue from Capitalism and Slavery, the 1940 work by the Marxist historian, Eric Williams.

However, what the Commissioners present as uncontested fact is a highly controversial issue. Most historians reckon slavery’s contribution to Britain’s prosperity somewhere between small and modest. And Professor David Eltis—who, according to the African American historian, Henry Louis Gates of Harvard University, is “the world’s leading scholar of the slave trade”—goes so far as to describe the contribution of slave-trading to the wider economy of Liverpool, Britain’s main slave-trading port in the mid-1770s, as “trivial”.

Those who present the ‘centrality’ of slavery to industrial growth as a simple fact are either ignorant or disingenuous.

IP: It is not always recognised that Britain and its Empire played a unique role in the ending of the Atlantic slave trade—and the elimination of other forms of slavery around the Empire. What is the evidence for this, and how does it affect the debate on reparations?

NB: Yet another context that reparations-advocates completely ignore is that the British were among the first peoples in the history of the world to abolish slave-trading and slavery in all their territories, in the early 1800s. They then used their global dominance, following the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, to suppress both the trade and the institution from the Pacific North-West, across Africa and India, to New Zealand. In mid-century, the Royal Navy devoted over 13 per cent of its total manpower to stopping slave-traffic between West Africa and Brazil.

At the same time, Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton’s idea that the key to ending the slave trade and slavery in Africa was to promote alternative, ‘legitimate’ commerce, was gaining traction. This led to the setting up of trading posts in West Africa, and then, when the merchants complained of the lack of security, a more assertive colonial presence on land. In 1851, having tried in vain to persuade its ruler to terminate the commerce in slaves, the British attacked Lagos and destroyed its slaving facilities. Ten years later, when an attempt was made to revive the trade in 1861, they annexed Lagos as a colony. Observe the developmental logic of ‘colonialism’ here: first, the humanitarian intent; then the promotion of commerce; and finally, the imposition of colonial rule.

Unlike the cheap contemporary performance of ‘decolonising’ virtue, the sustained British campaign against slavery was expensive in both lives and money. David Eltis reckons that nineteenth-century expenditure on slavery-suppression outstripped the eighteenth-century benefits. And the political scientists, Chaim Kaufmann and Robert Pape concluded that Britain’s effort to suppress the Atlantic slave trade alone in 1807–67 was “the most expensive example [of costly international moral action] recorded in modern history”.

IP: I am of Irish heritage, and so one obvious question for me is: if there should be reparations for slavery, then why should there not also be reparations for the harm done to my ancestors? Is that a reasonable question to ask, and how do those arguing for reparations respond to such challenges?

NB: The answer to this question exposes the racist bias of the case for reparations: only black victims matter. My ancestors were Scottish, not Irish. But they, too, suffered in the 1600s. They were Presbyterian Covenanters, who refused to have bishops and the Anglican Book of Common Prayer imposed on them. As a consequence, they had to worship in secret, because their meetings were banned. They fought battles that they lost. And they were hunted by government troops in the hills of Galloway. Do I feel their pain? Do I suffer ‘intergenerational trauma’? Not obviously. An awful lot has happened to change the fate of their descendants. Other causes have intervened. My condition is not at all theirs. Thank God in heaven!

And yes, of course, all manner of people suffered grievously in the past: medieval serfs and early industrial workers and white slaves. So why privilege enslaved Africans and point the finger only and unfairly at their white enslavers? The obvious answer is that such a distorted focus best serves the exploitation of white elites, who, knowing no history and terrified of being labelled racist, indulge in ‘imaginary guilt’.

IP: Is there evidence of slavery having left a permanent and current negative impact on certain nations?

NB: Common sense tells us that historic slavery is bound to have left its mark on the descendants of enslaved people. But that mark needn’t always be negative: some say that one of the legacies of enslavement is resilience.

The claim made by reparations-advocates, however, is that the contemporary descendants of slaves continue to suffer the effects of historic slavery—they suffer ‘intergenerational trauma’. But this is invariably asserted, not substantiated.

What’s more, if early 19th century slavery is responsible for the present plight of Caribbean people, how come that plight varies so much? There are considerable differences between Jamaica, with a GDP per capita in 2019 of $5,500, and Barbados, with a GDP per capita of $18,000 (which is an average for the world). Indeed, not only has Barbados achieved the world average in GDP per capita, but in 2019 life expectancy at birth in post-slavery Barbados was 14 years higher than in post-slave-trading Nigeria, literacy (in Barbados in 2014) was over 60 per cent higher (than in Nigeria in 2018), and Gross National Income per capita in $US in 2023 twelve times higher.

In fact, according to Tirthankar Roy, the West Bengali-born Professor of Economic History at the London School of Economics and author of The Economic History of Colonialism, upon gaining independence in the 1960s:

Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, and Barbados had the highest average income and literacy rates in the region, incomes per head were three to four times that in the long-independent Dominican Republic and Haiti, literacy rates were around 15 [per cent] in Haiti and 75-80 [per cent] in Jamaica. Almost certainly, public health was also similarly advanced.

As for the emergence of subsequent disparities between Barbados and Jamaica, Roy has this to say:

Jamaica after independence was particularly badly governed and saw a deep stagnation during 1972 and 1984, when standards of living actually fell. There are few countries in the world not engaged in civil war that had as bad a growth record as did post-independence Jamaica. Average income recovered only so much that its real average income is now what it had been around 1975. Overall, the West Indies region saw rather little economic growth in the 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, when many Asian countries (colonial or not) forged ahead. The reason was bad and corrupt government, not the burden of colonialism.

…nor the effects of historic slavery.

IP: The Church of England has been caught up in these arguments, because of the proposed Project Spire launched by the Church Commissioners. How do you think we should respond to the proposals that have been made?

NB: My view is that Project Spire is well intentioned. Those behind it believe that, in publicly repenting of the Church of England’s involvement in slave-trading—by devoting an initial £100m of the church’s assets to supporting black-led enterprises—they will make it more attractive to the descendants of enslaved Africans. The problem, however, is that the project is premised on ‘imaginary guilt’.

Guilt, like pain, can be good. When we put our hand next to a flame, it burns and, if our body is functioning well, it hurts. The pain we feel warns us of the physical damage being done and prompts us to pull our hand back. Similarly, the feeling of guilt pains us, alerting us to our having wronged someone and urging us to put things right again by apologising and repairing whatever damage we’ve done. The apology is itself an act of reparation, in that, by communicating to the injured party that we know we’ve done wrong, we signal that we share their moral view and thereby we begin to restore trust. However, if the wrong we’ve done is more serious than, say, an unkind word, we need to do more than merely apologise; we need to go further and restore what’s been lost or destroyed, or, if that’s not possible, offer some equivalent compensation. Guilt as a response to personal wrongdoing is healthy.

But false, imaginary guilt is not.

As I have reported in my book, several eminent historians have shown that the Church did not profit from slave-trading. Moreover, Project Spire is based on the cartoonishly racist—and racially divisive—narrative of white oppressors exploiting black victims. Since February 2024 I and others have been arguing in public that the project is historically groundless, ethically unjustified, procedurally reckless, and should be stopped. ‘We’ include a former incumbent of the Anglican Church’s premier professorial chair of moral theology, a professor of history at Cambridge, a professor of history at Oxford, a professor of international banking and author of a book on the South Sea Company, a KC and former Old Bailey judge, the Anglo-Indian director of an anti-racist body, and an eminent descendant of African slaves brought to Jamaica.

As I have reported in my book, several eminent historians have shown that the Church did not profit from slave-trading. Moreover, Project Spire is based on the cartoonishly racist—and racially divisive—narrative of white oppressors exploiting black victims. Since February 2024 I and others have been arguing in public that the project is historically groundless, ethically unjustified, procedurally reckless, and should be stopped. ‘We’ include a former incumbent of the Anglican Church’s premier professorial chair of moral theology, a professor of history at Cambridge, a professor of history at Oxford, a professor of international banking and author of a book on the South Sea Company, a KC and former Old Bailey judge, the Anglo-Indian director of an anti-racist body, and an eminent descendant of African slaves brought to Jamaica.

How has the Church—in the form of the Church Commissioners for England—responded to us? With defamation, evasiveness, silence, and intimidation. This is not behaviour befitting any organisation, especially not a Christian one, and most especially not the body responsible for managing the Church of England’s assets. Nor is it the response of a body confident of its own position.

This issue is not going to go away. Questions are now being asked in Parliament. If the Church Commissioners keep on digging, they risk embroiling themselves and the Church in a major national scandal, which reputations may not survive. That would be tragic. We beg them to stop, to listen, and, if they cannot answer, to turn around. Now, with the appointment of a new Archbishop of Canterbury, is the opportunity to turn over a new leaf.

IP: Thank you for your fascinating answers and observations. I am sure that you are right, and that this whole project needs a serious rethink.

Nigel Biggar is Lord Biggar of Castle Douglas, Regius Professor Emeritus of Moral Theology at the University of Oxford, and Distinguished Scholar-in-Residence at Pusey House, Oxford, and a priest in the Church of England.

Nigel Biggar is Lord Biggar of Castle Douglas, Regius Professor Emeritus of Moral Theology at the University of Oxford, and Distinguished Scholar-in-Residence at Pusey House, Oxford, and a priest in the Church of England.

Described as “one of the leading living Western ethicists” (by John Gray, formerly Professor of European Thought at the London School of Economics, New Statesman, 25 November 2020), Professor Biggar was appointed Commander of the British Empire “for services to higher education” in the 2021 Queen’s Birthday Honours list and named one of Prospect magazine’s Top Thinkers of 2024. In January 2025 he entered the House of Lords as a Conservative peer.

Among his most recent books are Reparations: Slavery and the Tyranny of Imaginary Guilt (Swift, 2025); Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning (William Collins, 2023, 2024), What’s Wrong with Rights? (Oxford, 2020), Between Kin and Cosmopolis: An Ethic of the Nation (2014), and In Defence of War (Oxford, 2013).

His hobbies include walking over battlefields. In 1973 he drove a Morris Traveller from Scotland to Afghanistan; and in 2015 and 2017 he trekked across the mountains of central Crete in the footsteps of Patrick Leigh-Fermor and his comrades, when they abducted General Kreipe in April-May 1944. He enjoys playing an anarchical card-game.

Buy me a Coffee

Buy me a Coffee

I’d say there are several things not mentioned here (perhaps they are in the book) that make the issue slightly more complex.

1) I suspect the assessment ‘slave-trading to the wider economy of Liverpool, Britain’s main slave-trading port in the mid-1770s, [was] “trivial”’ only factors in the direct contribution of slave-trading itself (i.e. the value of trading slaves) without taking into account the cheaper goods produced by those slaves. The vast majority of cotton imports in the 19th Century stemmed from American cotton plantations. I doubt very much that Britain’s corner of the cotton manufacturing industry contributed only a trivial amount to Britain’s economy.

2) During the time where slave-trading was legal in the empire, only a very small proportion of the population had any voting rights whatsoever. The same rich magnates trading in slaves/owning plantations/owning factories with terrible working conditions were the very same ones holding the reins of power, oppressing at home and abroad. To seek reparations from Britain today (presumably at the taxpayer’s expense) would be to extract money from the ancestors of people who had zero voting rights whatsoever because of the actions of the people who denied them their voting rights.

3) I see little in any of the discussions around reparations about seeking reparations from West African countries. The truth of the matter is Africans were also directly involved in the slave trade, kidnapping and selling those of other ethnic groups/tribes in exchange for goods/money. If there is a legitimate moral case in favour of reparations, then reparations of the ancestors of these enslavers should also be sought.

4) I think one of the issues with pressing too hard on the ‘well nobody alive was involved in the slave trade so it’s not fair for us to pay reparations’ line means the wealth generated from the slave trade (and the cheap goods it produced) also isn’t ‘ours’. And if the ill-gotten wealth isn’t ours, in what sense can we complain if it is then given away?

Re your point (1), I think that the cost of raw cotton has always been small compared to the cost of turning it into clothes. That is true even today when cotton is not picked by slaves and weaving is fully mechanised.

I’d add a point about payment: from whom to whom? Why should the British children of a West Indian father and English mother (for example) pay anything; and why should any payment be given to corrupt Third World politicians rather than their peoples?

Your point (4) raises a fascinating issue about the passage of time. Everybody (including me) thinks it is right to return Old Masters looted by the Nazis to the families of Jews dispossessed of them. (Is it crucial that specific families can be identified – and also specific goods, whereas money is fungible?) In contrast, nobody thinks that British people having French surnames running provably further back than the Huguenots (i.e. running back to the Norman Conquest) should pay reparations to the rest of us, even though they are still wealthier on average nearly a thousand years later. (“A study of family surnames between 1861 and 2011 showed that bearers of Norman surnames were, on average, slightly more than 10 percent wealthier than the mean” – Daniel Hannan, How we invented freedom and why it matters.)

i was in Ghana in the summer, visited St George’s Castle, with the soberingly named “door of no return” which says it all really, and had the privilege to meet with local Christian leaders, including the director of the museum at the castle. We discussed these issues, listened to what they had to say, listened to young people there, including those who are mixed race, because they are the heirs of children fathered by white soldiers. It was humbling, thought provoking, listening to these educated and articulate Ghanaians.

Admittedly a small sample of people, yet not one of them was in favour of reparation. There was the obvious questions from them of who, how and why, withthe fear that reparation money would be wasted anyway. One comment was, isn’t this just so you can feel less bad about whjst you’ve done? i think this is a bit harsh, as restorative justice is so important, and we discussed that, but it is still a valid question. Another comment that stayed with me was “isn’t this just another example of colonialism, you deciding what you need to do to put things right, rather than asking us?” Sadly, i didn’t know enough about the process to know how valid a critique that is, but again an interesting comment.

Interestingly their concerns were more about the injustices of the present than reparation for the past. An oft quoted example was that although Ghana exports $1bn worth of cocoa beans it exports only $34m worth of chocolate (which has a much higher worth), because historically the means of producing chocolate have been denied them. What i heard amongst the young people was not pain from the past but a real desire for them to be enabled to build their own future, and the frustrations of being up against a powerful western ecomomy (which pays our pension fund) resisting their efforts.

Wow, what a challenging and helpful comment. Thanks so much.

Aside: the chocolate example is misleading. Food commodities are always traded much more than consumer foodstuffs. The reason is that shipping consumer-grade food is expensive: you have to comply with the food standards, inspection regimes, and labelling requirements of the destination market, pack it all safely and securely, and oftentimes refrigerate it for the journey. Shipping a commodity that will be processed extensively before it goes near a consumer is much simpler and cheaper. Companies like Nestle, Kelloggs, Coca Cola etc. don’t ship their products around the world, they make in the market they sell in. Even something as simple as sugar is shipped in a rough form (where it often has be drilled out of the hull of the ship) to be refined to be bought by consumers in the UK.

A bigger issue is the refusal of Western institutions to invest or partner in the fossil fuel industry in Africa (e.g. World Bank in 2010, UK government 2021), thereby driving African nations to align with Russia and China. Not very long ago Ghana had one of the fastest-growing economies in the world, but has reverted to blackouts. Many Africans still cook indoors using smoky biofuels that cause poor respiratory health. All this is due to another example of virtue-seeking, regarding climate change.

But I would add that, even if investment, is available, it is very hard indeed to start and run a successful business in a place where corruption is endemic.

I don’t find the argument for reparations for slavery convincing, for many of the arguments given. However, looking at Adam’s and Dominic’s comments – the argument that the world economy is currently skewed in favour of former colonialist powers and their companies eg Coca Cola perhaps) suggests to me that any reparations (or readjusting of the financial rules) should rather be on the basis of colonialism and historic European/American economic dominance.

There is much important information and analysis in this interview, but there are two important elements missing:

1. As Orlando Patterson, the Jamaican-born professor of sociology at Harvard wrote in ‘The Sociology of Slavery’, the islands of the Caribbean are unique in world history as slave societies that were artificially created solely for the production of agricultural goods, mostly sugar. The impact of that distortion has not completely disappeared.

2. It was slavery in the most extreme racialised form – powerful white masters convinced of their superiority over powerless and brutalised black slaves whose cultures, languages and religions were seen as worthless and suppressed. And with lasting effect on subsequent white perceptions.

For these reasons the legacy of slavery in the Caribbean is of a different order to other forms of enslavement and injustice.

Whilst the concept of intergenerational trauma is slippery, I believe it has force – evidenced in the broadly different senses of bearing and self-assurance between Caribbean and West African descended people on Tottenham High Road today.

It is arguable that the payment of reparations (by Franz Fanon for example) consolidates rather than assuages that sense of psychic injury, but the question of whether or how the legacy of that damage should be addressed needs serious thought and response, not least by the Church of England as the bearer of our nation’s moral and spiritual identity during the centuries of our enslaving; and whether or not money should be part of that recognition and apology.

Personally I think that some sort of permanent public expression of repentance and sorrow – for example a statue in Westminster Abbey, if not the fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square – is at least appropriate.

Not to mention the removal of statues, or sending them for a swim in Bristol docks…

Sensible points from Lord Biggar. As he mentions the UK did a lot to abolish slavery so should not be required to pay reparations.

There may arguably be a case for reparations from old aristocrat families, companies and institutions like the Royal family and Church of England where it is proved they benefited financially from owning slaves pre 1800 and investing in slave trading companies. Yet even that is arguable for the Church of England at least as the article makes clear and anyway should be voluntary

while urban workers in early industrial England were not slaves, because they had legal rights, their conditions of work and living were often quite appalling.

But were they worse than in working the land, which they had quit? Arguably they traded job security for a *higher* standard of living. The point is that the Industrial Revolution made an alternative possible to a hierarchical farming-based society for the first time in human history. (Actually the second time, because no landed aristocracy was mandated – in fact it was actively prevented by Jubilee regulations – in ancient Israel’s written Laws of Moses.) Also, the cities *concentrated* the poor, enabling them to organise – for revolution in Russia and for Trade Unions in Britain.