I am reposting here the article I wrote last year—because I have been struck again how often the message of Christmas is summed up as ‘Jesus was born in a stable’, both within and beyond the church.

If we take the New Testament texts seriously, this simply is not true, so cannot be the heart of the Christmas message. Jesus comes close to us, right here, not over there down an alleyway. This has consequences for our preaching and speaking; see the end of the page for related posts that explore this.

I am sorry to spoil your preparations for Christmas before the Christmas lights have even gone up—though perhaps it is better to do this now than the week before Christmas, when everything has been carefully prepared. But Jesus wasn’t born in a stable, and, curiously, the New Testament hardly even hints that this might have been the case.

I am sorry to spoil your preparations for Christmas before the Christmas lights have even gone up—though perhaps it is better to do this now than the week before Christmas, when everything has been carefully prepared. But Jesus wasn’t born in a stable, and, curiously, the New Testament hardly even hints that this might have been the case.

So where has the idea come from? I would track the source to three things: issues of grammar and meaning; ignorance of first-century Palestinian culture; and traditional elaboration.

The elaboration has come about from reading the story through a ‘messianic’ understanding of Is 1.3:

The ox knows its master, the donkey its owner’s manger, but Israel does not know, my people do not understand.

The mention of a ‘manger’ in Luke’s nativity story, suggesting animals, led mediaeval illustrators to depict the ox and the ass recognising the baby Jesus, so the natural setting was a stable—after all, isn’t that where animals are kept? (Answer: not necessarily!)

The second issue, and perhaps the heart of the matter, is the meaning of the Greek word kataluma in Luke 2.7. Older versions translate this as ‘inn’:

And she brought forth her firstborn son, and wrapped him in swaddling clothes, and laid him in a manger; because there was no room for them in the inn. (AV).

There is some reason for doing this; the word is used in the Greek Old Testament (the Septuagint, LXX) to translate a term for a public place of hospitality (eg in Ex 4.24 and 1 Samuel 9.22). And the etymology of the word is quite general. It comes from kataluo meaning to unloose or untie, that is, to unsaddle one’s horses and untie one’s pack. But some fairly decisive evidence in the opposite direction comes from its use elsewhere. It is the term for the private ‘upper’ room where Jesus and the disciples eat the ‘last supper’ (Mark 14.14 and Luke 22.11; Matthew does not mention the room). This is clearly a reception room in a private home. And when Luke does mention an ‘inn’, in the parable of the man who fell among thieves (Luke 10.34), he uses the more general term pandocheion, meaning a place in which all (travellers) are received, a caravanserai.

The difference is made clear in this pair of definitions:

Kataluma (Gr.) – “the spare or upper room in a private house or in a village […] where travelers received hospitality and where no payment was expected” (ISBE 2004). A private lodging which is distinct from that in a public inn, i.e. caravanserai, or khan.

Pandocheion, pandokeion, pandokian (Gr.) – (i) In 5th C. BC Greece an inn used for the shelter of strangers (pandokian=’all receiving’). The pandokeion had a common refectory and dormitory, with no separate rooms allotted to individual travelers (Firebaugh 1928).

The third issue relates to our understanding of (you guessed it) the historical and social context of the story. In the first place, it would be unthinkable that Joseph, returning to his place of ancestral origins, would not have been received by family members, even if they were not close relatives. Kenneth Bailey, who is renowned for his studies of first-century Palestinian culture, comments:

Even if he has never been there before he can appear suddenly at the home of a distant cousin, recite his genealogy, and he is among friends. Joseph had only to say, “I am Joseph, son of Jacob, son of Matthan, son of Eleazar, the son of Eliud,” and the immediate response must have been, “You are welcome. What can we do for you?” If Joseph did have some member of the extended family resident in the village, he was honor-bound to seek them out. Furthermore, if he did not have family or friends in the village, as a member of the famous house of David, for the “sake of David,” he would still be welcomed into almost any village home.

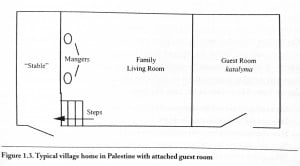

Moreover, the actual design of Palestinian homes (even to the present day) makes sense of the whole story. As Bailey explores in his Jesus Through Middle-Eastern Eyes, most families would live in a single-room house, with a lower compartment for animals to be brought in at night, and either a room at the back for visitors, or space on the roof. The family living area would usually have hollows in the ground, filled with straw, in the living area, where the animals would feed.

Moreover, the actual design of Palestinian homes (even to the present day) makes sense of the whole story. As Bailey explores in his Jesus Through Middle-Eastern Eyes, most families would live in a single-room house, with a lower compartment for animals to be brought in at night, and either a room at the back for visitors, or space on the roof. The family living area would usually have hollows in the ground, filled with straw, in the living area, where the animals would feed.

This kind of one-room living with animals in the house at night is evident in a couple of places in the gospels. In Matt 5.15, Jesus comments:

Neither do people light a lamp and put it under a bowl. Instead they put it on its stand, and it gives light to everyone in the house.

This makes no sense unless everyone lives in the one room! And in Luke’s account of Jesus healing a woman on the sabbath (Luke 13.10–17), Jesus comments:

Doesn’t each of you on the Sabbath untie your ox or donkey from the manger [same word as Luke 2.7] and lead it out to give it water?

Interestingly, none of Jesus’ critics respond, ‘No I don’t touch animals on the Sabbath’ because they all would have had to lead their animals from the house. In fact, one late manuscript variant reads ‘lead it out from the house and give it water.’

What, then, does it mean for the kataluma to have ‘no space’? It means that many, like Joseph and Mary, have travelled to Bethlehem, and the family guest room is already full, probably with other relatives who arrived earlier. So Joseph and Mary must stay with the family itself, in the main room of the house, and there Mary gives birth. The most natural place to lay the baby is in the straw-filled depressions at the lower end of the house where the animals are fed. The idea that they were in a stable, away from others, alone and outcast, is grammatically and culturally implausible. In fact, it is hard to be alone at all in such contexts. Bailey amusingly cites an early researcher:

What, then, does it mean for the kataluma to have ‘no space’? It means that many, like Joseph and Mary, have travelled to Bethlehem, and the family guest room is already full, probably with other relatives who arrived earlier. So Joseph and Mary must stay with the family itself, in the main room of the house, and there Mary gives birth. The most natural place to lay the baby is in the straw-filled depressions at the lower end of the house where the animals are fed. The idea that they were in a stable, away from others, alone and outcast, is grammatically and culturally implausible. In fact, it is hard to be alone at all in such contexts. Bailey amusingly cites an early researcher:

Anyone who has lodged with Palestinian peasants knows that notwithstanding their hospitality the lack of privacy is unspeakably painful. One cannot have a room to oneself, and one is never alone by day or by night. I myself often fled into the open country simply in order to be able to think.

In the Christmas story, Jesus is not sad and lonely, some distance away in the stable, needing our sympathy. He is in the midst of the family, and all the visiting relations, right in the thick of it and demanding our attention. This should fundamentally change our approach to enacting and preaching on the nativity.

But one last question remains. This understanding of the story has been around, even in Western scholarship, for a long, long time. Bailey cites William Thomson, a Presbyterian missionary to Lebanon, Syria and Palestine, who wrote in 1857:

It is my impression that the birth actually took place in an ordinary house of some common peasant, and that the baby was laid in one of the mangers, such as are still found in the dwellings of farmers in this region.

And Bailey notes that Alfred Plummer, in his influential ICC commentary, originally published in the late nineteenth century, agreed with this. So why has the wrong, traditional interpretation persisted for so long?

I think there are two main causes. In the first place, we find it very difficult to read the story in its own cultural terms, and constantly impose our own assumptions about life. Where do you keep animals? Well, if you live in the West, away from the family of course! So that is where Jesus must have been. Secondly, it is easy to underestimate how powerful a hold tradition has on our reading of Scripture. Dick France explores this issue alongside other aspects of preaching on the infancy narratives in in his excellent chapter in We Proclaim the Word of Life. He relates his own experience of the effect of this:

[T]o advocate this understanding is to pull the rug from under not only many familiar carols (‘a lowly cattle shed’; ‘a draughty stable with an open door’) but also a favourite theme of Christmas preachers: the ostracism of the Son of God from human society, Jesus the refugee. This is subversive stuff. When I first started advocating Bailey’s interpretation, it was picked up by a Sunday newspaper and then reported in various radio programmes as a typical example of theological wrecking, on a par with that then notorious debunking of the actuality of the resurrection by the Bishop of Durham!

So is it worth challenging people’s assumptions? Yes, it is, if you think that what people need to hear is the actual story of Scripture, rather than the tradition of a children’s play. France continues:

The problem with the stable is that it distances Jesus from the rest of us. It puts even his birth in a unique setting, in some ways as remote from life as if he had been born in Caesar’s Palace. that’s the message of the incarnation is that Jesus is one of us. He came to be what we are, and it fits well with that theology that his birth in fact took place in a normal, crowded, warm, welcoming Palestinian home, just like many another Jewish boy of his time.

And who knows? People might even start asking questions about how we read the Bible and understand it for ourselves!

PS I would love to hear from anyone who has had the courage to re-write the children’s Christmas story to fit with this reading—and managed to pull it off without getting lynched!

Additional note

I am grateful to Mark Goodacre for drawing my attention to an excellent paper on this by Stephen Carlson, one of his colleagues at Duke. The paper was published in NTS in 2010, but is available on Carlson’s blog for free. Carlson presses the argument even further by arguing three points:

1. He looks widely at the use of kataluma and in particular notes that in the Septuagint (LXX, the Greek translation of the OT from Hebrew in the second century BC) it translates a wide variety of Hebrew terms for ‘places to stay.’ He thus goes further than Bailey, agreeing that it does not mean inn, but instead that it refers to any place that was used as lodgings.

2. He looks in detail at the phrase often translated ‘there was no room for them in the kataluma‘ and argues that the Greek phrase ouch en autois topos does not mean ‘there was no room for them’ but ‘they had no room.’ In other words, he thinks that they did stay in the kataluma, but that it was not big enough for Mary to give birth to Jesus in, so she moved to the main room for the birth, assisted by relatives.

3. He believes that Bethlehem was not Joseph’s ancestral home, but his actual family home, for two reasons. Firstly, we have no record of any Roman census requiring people return to their ancestral home. Secondly, he argues that the phrase in Luke 2.39 ‘to a town of their own, Nazareth’ doesn’t imply that they were returning to their home town, but that they then made this their home. We already know this is Mary’s home town, and it would be usual for the woman to travel to the man’s home town (Joseph’s Bethlehem) to complete the betrothal ceremonies. After Jesus is born, they then return together to set up home near Mary’s family.

The kataluma was therefore in all likelihood the extra accommodation, possibly just a single room, perhaps built on the roof of Joseph’s family’s home for the new couple. Having read this, I realised that I had stayed in just such a roof-room, jerry-built on the roof of a hotel in the Old City of Jerusalem, in the lee of the Jaffa Gate, in 1981. It was small, and there was certainly no room to give birth in it!

(You can stay there too, by booking here. The site includes the view we had from the roof!)

Related Posts:

Stephen Kuhrt did take up the challenge to re-write a nativity play on the basis of this.

I preached in this way at our main carol service

We also had a sketch based on the idea that a birth might not change very much as a lead-in

Other posts on Christmas include:

Exploring what time of year Jesus was in fact born

Whether Luke got the year of Jesus’ birth wrong

What people are really doing in Christmas traditions

I work freelance. If you have valued this post, would you consider donating £1.20 a month to support the production of this blog?

Buy me a Coffee

Buy me a Coffee

Great post, Ian! Thank you.

Coincidently, we have just been running a series of Advent seminars here at Newman Uni looking at the development of the nativity story into the form we have it today.

Your question about the animals (lending to the idea that Jesus was born in a stable) first appears in the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew (ch 14). Interestingly it draws upon a rather odd variant of Habakkuk 3:2 (LXX). Also you will see that the event occurs not in a stable either, but in a cave. G. Ps-Matt. draws upon the earlier Protevangelium of James which introduces the cave motif.

The G. Ps-Matt. text reads:

“And on the third day after the birth of our Lord Jesus Christ, the most blessed Mary went forth out of the cave, and entering a stable, placed the child in the stall, and the ox and the ass adored Him. Then was fulfilled that which was said by Isaiah the prophet, saying: The ox knoweth his owner, and the ass his master’s crib. [2] The very animals, therefore, the ox and the ass, having Him in their midst, incessantly adored Him. Then was fulfilled that which was said by Abacuc the prophet, saying: [3] Between two animals thou art made manifest. In the same place Joseph remained with Mary three days.”

Interestingly the animals have stayed, but the cave (with midwives) has gone in western tradition. Although they still remain in the orthodox tradition.

Richard, thanks very much for the links. Very useful/

this is a reply to Ian Paul.

as I was sent to the wrong website the bridge.co.uk.

Re your theory Jesus was not born in a stable…….

There are many writing of parables in the bible as you know. Many have no logical explanation.

I am just wondering why you feel compelled to change the course of history, shattering all those little childrens dreams, Next you will be telling us that there is no father Christmas 🙁

Test the spirits, the scribes have not always been faithful.

It is Faith in god (not facts) that we believe.

Merry Christmas.

I am Jennifer.

Have you taken into account that Mary may not have been welcome becuase of her pregnancy? The family would know that the child had been conceived before they were married. ……

Tricia, I think that is an interesting question. But I am struck by the fact that Matthew’s account, written consistently from a male perspective, includes this as a problem. By contrast, Luke’s account, written from the women’s perspective, does not mention this as an issue, and instead focusses on the miraculous nature of the conception.

So it seems as though Luke does not think this important enough to mention. If we do, then I think we are reading something into Luke’s account which is not there.

please may I quote from this in an article for our church magazine?

Of course! Do mention the blog.

Perdón, no hablo inglés, pero me ha parecido muy interesante el artículo. Sin embargo me queda una duda: Usted mismo ha dicho que Lucas solo ha colocado en su relato aquello que ha considerado importante de mencionar… entonces me pregunto: ¿Para qué mencionar el pesebre si era lo más normal en las familias y en las casas de entonces? Pienso que para Lucas debe tener un significado especial que quiere poner en evidencia, quizá conectado con los otros personajes de su relato, como los pastores, por ejemplo. Gracias.

Translation: Sorry, I do not speak English, but I found very interesting article. However a question remains for me: You said yourself that Luke has just placed in his account what has been considered important to mention … then I ask: Why mention the crib if it was normal in families and homes so? I think for Luke it must have a special meaning you want to highlight, perhaps connected with the other characters in his story, like the shepherds, for example. Thank you.

An excellent article, Ian – most helpful.

I have amended my Christmas Day sermon, removing references to stables, etc, but I’m not brave enough to introduce the more authentic interpretation to the congregation as yet!

Have a great Christmas.

Next year perhaps…!

Old news. A more interesting article would be effective techniques for engaging clergy who aren’t as informed.

Well one way would be to encourage them to read this blog…?

I also offer two or three ways of addressing the issue in preaching at the links given below.

If, of course, the family had to travel at all. In Matthew their home is in Bethlehem, and Jesus is born in the house. They only go to Nazareth to avoid the Herodian kings.

Yes, good point. Stephen Carlson makes the point in his posts, which I link to in my ‘Additional note’ above.

I am inclined to think that Nazareth was Mary’s home town, Bethlehem Joseph’s. Joseph may have moved north to be involved in the massive building works in Sepphoris which he may have preferred to finding employment in the ongoing construction of the Herodion whether for professional or political reasons.

Kenneth Bailey has himself written a nativity play. See http://www.amazon.co.uk/Open-Hearts-Bethlehem-Set/dp/0830837574 and http://www.amazon.co.uk/Open-Hearts-Bethlehem-Christmas-Musical/dp/0664228720

Thomas How fascinating! Thanks for the links.

Sadly it may be too elaborate to pull of in most English churches where the nativity play tradition often involves (only) very young children or is done by a handful of adults but in either case pretty ad hoc. In my childhood in Germany we used to practice for weeks to perform a pretty serious play and the 8 year olds would have been among the very youngest players, not the oldest.

That sounds like a tradition worth learning from. I wonder why it has devolved to children in the UK?

Jesus may not have been born at all, let alone in a stable. There may well have been a real child Yeshua born to a certain Mariam daughter of Yehoyaqim from a father unknown, but the rest of the story is varying degrees of historical fiction, little of which we’ll ever be able to establish as fact.

So really, does it matter all that much if we place his birth in a stable, or a cow-byre, or the 1st century Palestinian version of a garage (i.e. the place in your home where you park your mode of transport, be it a car or a mule…)?

Religion relies on pretty, idealized pictures. We draw Mariam as a rosy-cheeked alabaster-skinned beauty when in all probability the real woman, if she ever existed, would have been as sallow, dark-haired and pock-marked as any other Jewish woman in an era of poor hygiene, dietary deficiencies and short life expectancy. But reality counts for nothing in an idealized story. As the messiah’s mother, Mariam had to be pretty, delicate, perfect and virginal. And as God lowering himself to take on human form, Jesus had to be born in the most modest surroundings imaginable.

The stable is a Christian trope just like Mariam as a porcelain doll is a Christian trope. Legends rely on tropes, which is why it can be dangerous to start investigating the truth behind them. I mean, if Christ wasn’t born in the humblest of humble circumstances, then God didn’t completely abase himself when he came to earth, did he? If Christ was born in the equivalent of a comfortable middle-class home, what happens to those other Christian tropes of humility and self-abasement?

The Catholics have got it right yet again: best stick to the traditional image of the manger and the farmyard animals otherwise you’ll find yourself worshipping a middle-class Jesus. And who can relate to a bourgeois god? Bourgeois Worshipful Doctors and their bourgeois flocks, perhaps. But anyone else? Or is god just for the middle classes these days?

Whatever the appeal of the images that evolved throughout the era of Christendom, the brutal humiliation and execution by heathen ‘invaders’ would detract from the credibility of the gospel among both both Jews and Greeks.

Far from any mass appea, the gospel of One whose life succumbed to the power of Rome offered little hope of escape from adversity.

Rather than resorting to a reliance upon the kind of ‘wisdom’ by which mankind could even rationalises its total usurpation of natural rights, it pleased God to effect the power of redemption through the antithesis of worldly wisdom: by heralding Christ crucified and risen as only means of escape from the retributive reprobation of those who sear away their consciences with the hope of impunity.

As scripture puts it: ‘I will destroy the wisdom of the wise and being to nothing the understanding of the prudent’. The gospel is calculated to damn the proud.

Jesus in a stable is no less an aristocrat. Certainly a bourgeois Jesus in a stable would be odd, but not a noble one.

Good article, Ian Paul. There are, lesser known, others who have been brave enough to share what you have regarding the difference between the traditional view of where Jesus was born and the truth of what is written; they haven’t been lynched.

I have a question regarding Kenneth Bailey’s comment on what Joseph would have said regarding his ancestry. If Joseph, Mary’s husband (and the supposed father of Jesus), in Luke 3:23-24, is the son of Heli, who was the son of Matthat, who was the son of Levi, (and so forth)… How do you reconcile that with Jesus’ genealogy and of THATJoseph being the son of Jacob, who was the son of Matthan, who was the son of Eleazar,…in Matt 1:14-16? (The context in this section of Matthew, though, is of who begat whom.).

Thanks Barbara. The question of the interrelation of the two genealogies is quite a complex one, which I have not really looked into.

But it is clear from Luke’s account that he was aware of the anomaly of doing a genealogy only for it to fail at the last hurdle…

The Joseph in Matt. is Mary’s FATHER, not “husband. Matt says there are 14 generations in the last line . If Joseph is Mary’s “husband” there would be only 13. Is was not that common to have married a person with the same first name as your father but it happens, even today.

I think we need to pay attention the way that Matthew counts his generations—and note that he misses many out in order to make the numbers work.

This is a theological, not historical, list. ‘Father’ can simply mean ‘ancestor’.

The one thing that still prompts me to question this is the reaction that might have been given to Mary, perceived as an unfaithful betrothed woman which in this culture is the equivalent of being an adultress and worthy of being stoned. Surely whatever norms for Joseph’s welcome could have been affected by Mary’s status and gossip surrounding her?

Charlotte, yes this is interesting, and has been asked earlier in the comments too.

We might speculate on the impact of this—but this remains speculation. It is striking that Matthew’s account, written from a male perspective, is bothered about this, but Luke’s by contrast, told from the women’s perspective, does not even mention it as an issue.

This might say something about the different concerns—but might also suggest that it wasn’t such a big deal for some reason. Luke’s account of the birth is very compressed, though his account of conversations between people is quite detailed.

The evidence is thin and some believe that there was a difference between attitudes in Galilee and Judea but generally speaking I think it’s fair to say that sex between a betrothed couple was frowned upon but it would not be worthy of stoning. I don’t expect that Joseph went around telling everyone that he was not the father although suspicions may have arisen early because at/near the time of conception Mary was in Judea (with Elizabeth) and Joseph in Galiee…

Thomas do you know of any primary sources on such attitudes?

Dear sir, having once been Protestant, I completely follow your line of reasoning. You find a point in history that agrees with your premise, then work your way forward in time quoting authors that also agree. However, you completely ignore the oldest expression of Christianity, and what she says regarding the Nativity. You ignore iconography, which always has portrayed the Nativity being in a cave. And you rely on Western expressions, which have been largely divergent from orthodox, and Orthodox, Christianity for nearly 1000 years. Truth cannot be found downstream, but nearer the source. I suggest a more thorough study, of original sources, closest to the beginning, than premises and surmises propagated by those drinking down stream.

I don’t ignore it so much as question whether it offers us anything other than a long tradition, which might not have any connection with the historical events.

As Richard Goode points out above, the cave tradition originates with the Protevangelium of James and is picked up in Pseudo Matthew. These apocryphal texts are later than the gospels, and recognised as having non-historical dogmatic agendas.

So in fact I am following your advice and returning to the source of the stream, rather than drinking downstream.

I recently recorded a small MP3 that presents the birth of Christ in a similar way. It is posted on the website of Spirit and Truth Fellowship International (stfonline.org). We also believe that He was born Sept. 11th 3BC and the Magi or wise men didn’t arrive until over one year later. In addition to the short MP3 there are several video teachings on the STF website relating to the Christ’s birth.

The MP3 link is below.

Merry Christmas,

John J Sandt

Allentown, PA

http://stfonline.org/mp3/T-was-The-Day-Before-Christs-Birth.mp3

Thanks John. I have posted on the date of Jesus’ birth, and I think the Magi coming later is fairly well established too.

I have read an article by (the late?) Dick France many years ago on Third Way where he took this position too (about Jesus being born among family; and about not romanticizing his birth to the point that the Biblical characters involved do not challenge us to follow their examples). However, I just preached last Sunday on “Focus on Joseph” using Mt 1:18-25 (the lectionary reading). I wondered in that sermon about how receptive Joseph’s extended family would have been to the couple, who to human eyes were about to have a child conceived out of wedlock. So, when Joseph took his step of faith to accept the angel’s word AND presumably Mary’s story, he also probably chose ostracism from his family. Otherwise, who would not make room in the “inn” for a birthing event?

It is probably examples like Joseph’s that led Jesus later on to either (i) relativize the importance of family; or (ii) to broaden the concept of family.

Priyan

Sure—but there is a bigger question about whether we should be preaching on what we think might have happened, or what the texts tell us happened.

What I am doing here is not so much speculating on things we don’t find in the text, but setting the text itself in its historical context, which is a very different thing.

IF we are preaching on Scripture, it seems to me that we need to take our cue from the Scripture as to what was important, and what wasn’t. I don’t believe in using the text as a window onto something else…

Mr. Ian Paul, have you did any research on the Cenaculo in Jerusalem?

Why did the Jewish authorities did not permit Pope Francis to celebrate a mass in there?

Do you know what lies in the basement of that building:

Do you Know whose house was at the time of Jesus:

Do you Know under that building lies the tomb of David”

Finnally, a what distant is that building from the place where Jesus was buried just for a short time?

Tere are more question to ask

but I will reserve them for another time.

No I haven’t, but you would need to convince me about the archaeology. Many of the ‘traditional’ sights in Jerusalem bear no relation to the historical sites…

The Carlson essay is very helpful and informative and I have already circulated it – thanks for posting this, Ian.

I know of one vicar who has already changed his message on radio because of this – it wasn’t popular!

Great. But there are ways and ways of being unpopular…I didn’t get any negative reaction from my preaching on this the other week..

His reaction wasn’t from a church congregation but from the radio producer who had played the innkeeper in his school nativity play and was now upset to think that he might not have existed!

” I mean, if Christ wasn’t born in the humblest of humble circumstances, then God didn’t completely abase himself when he came to earth, did he? If Christ was born in the equivalent of a comfortable middle-class home, what happens to those other Christian tropes of humility and self-abasement?”

Lighten up, Etienne. There were poorer people then even than the traditional picture – like the single mother cast out of her home, or the mentally ill living in graveyards like ‘Legion’.

ANY kind of Incarnation would have an an abasement for Almighty God, and the true abasement wasn’t relative earthly poverty but leaving the glory of heaven to face death on the Cross. It is the absence of any message of the Cross (the purpose of the Incarnation in the first place) that undermines the weak messages most mainline Christians – especially Anglican bishops – preach at this time of the year. 2 Corinthians 8.9 makes this point clearly enough: ‘Though he was rich, for your sake he made himself poor so that by his poverty you might become rich.’ The poverty was not economic but ontological.

Even so, you cannot call Jesus’ upbringing ‘the equivalent of a comfortable middle-class home’. There really is no comparison between the first century and the present. While some people were conspicuously rich, most people lived a fairly hand to mouth existence, including journeyman carpenters and builders, without pensions, much property or much in the way of savings.

Thanks Brian. I think this is the most important issue: God did not need to demonstrate humility by being born in a stable, but by being born. This is certainly what Paul thinks.

And it is amazing that people project contemporary socio-economics on the first century by talking about ‘the middle class.’ It didn’t exist.

I wrote about this very issue in my book Beginnings and Endings – and was surprised by the negative reaction I got from some readers – in particular those who were completely wedded to the idea that Jesus “neede” to have been born as an outcast in order to relate to those who don’t fit into society.

Another feature of the story is that Luke “bookends” the gospel with 2 kataluma – the one where there was no room at the beginning; the one where he had the last supper at the end. Luke liked that kind of “bookending” technique in his writing, does it a lot. SImilarly with Zechariah’s silence and Jesus’ blessing.

Maggi, that’s really interesting. What has struck me more and more forcefully is the way that the stable secularises the story. If Jesus’ humility is found in his being born in a stable, then we can dispense with the humility of the incarnation. So there is no need for pre-existence or divinity. Yet in Paul (and elsewhere in the NT) it is the incarnation which is the prime vehicle for communicating this.

Yes, I agree with you on the bookends. But it is also interesting that, at that point (the last supper preparations), Luke (contra Matthew) follows Mark word for word.

That’s precisely what I was saying in my reply to Etienne – that the Incarnation is the abasement, not the actual place where Jesus was born.

But I don’t think the two uses of ‘kataluma’ amount to a ‘bookending’. Luke 2.7 isn’t the beginning and Luke 22.12 isn’t the end. And ‘to kataluma’ is already in Mark 14.14. We may see ‘patterns’ which weren’t really in the writer’s mind, just in his sources.

Yes, but you are being a little rigid here. They are near beginning and end…about the same distance in fact. I note the observation that Luke follows Mark here—which Matthew does not. That could well suggest design on Luke’s part.

A single word (one of them already in Mark) is a bit much to make into a not-quite “bookend” – I think it ‘rigid’ to insist otherwise. Other patterns in Luke are a bit more strongly based, e.g. the step-parallelism between John and Jesus that John Nolland notes in his commentary, or the way that Luke-Acts begins in Jerusalem and then extends all the way to Rome.

I am sorry, but this is not correct. Too clever by far. Outside the Gospel of St Luke kataluma frequently has the meaning of inn. The text says that that Jesus was laid in a manger because there was not space for them in (or: inside) the inn. Then it was outside the normal lodging and through milennia this place has been interpreted as a stable. Broaden your references for kataluma! There are many synonyms not just pandocheion. Anyhow, the operating word here is manger, phatne, which makes the profound verticality of the text, from the emperor to the stable.

OK—but why are we looking outside the gospel of Luke? We need to pay attention to two things:

1. Luke was writing in a (relatively sophisticated) koine Greek, and not classical. Moreover, his language and thought is significantly shaped by the Septuagint. So this is where we need to look to understand the semantic range of the term. As Carlson points out, kataluma is used for a range of things, but not what we would call an ‘inn’.

2. As Maggi points out above, Luke is fond of ‘bookending’, and it is no coincidence that a kataluma occurs at both the start and end of the gospel. It would be odd if the word meant something quite different in the two locations.

I would agree with you that there is a strong implicit contrast between imperial power and the humility of the manger. But this is a contrast between Jesus and the emperor and not primarily a contrast between Jesus in his pre-existence and in his earthly existence. As I say elsewhere, the NT does not use the manger tradition to make this point. Becoming human is enough!

Actually it may well be a coincidence – Luke doesn’t make great play of the word. The point is that no version translates Mark 14.14 ‘to kataluma’ as ‘inn’, and neither presumably does Tor Hauken. Since Luke *does use a different word for ‘inn’ in 10.34, the presumption should be that 2.7 doesn’t refer to an inn.

Yes, absolutely.

I wonder why you refer to Jesus’s presumed birthplace as a “Palestinian” home and to “Palestinian culture’, and why Kenneth Bailey is said to be renowned for his studies of “first century Palestinian culture”. Jesus was a Jew and he was born, whether in a stable or a private house, in Judea, the kingdom of the Jews. Judea was renamed “Palestina” by the Romans in the second century CE, after they conquered Judea and renamed it in an attempt to erase Jewish identification with the land of Israel. You appear to have attempted to do the same thing.

Melanie, thanks for commenting.

I used to agree with you (possibly from reading your articles!). But I then realised two important issues:

1. Until the modern era, the term was consistently used as a geographical and cultural term, not a political or still less religious one. When the Romans used the term to rename the region, they were not displaced one religio-political term with another, but replacing a religio-political term with a strictly geographical one. I think this geographical sense is the one intended in the language of the ‘British Mandate for Palestine.’

2. It is clear that the term has long historical roots, pre-dating the Romans. As I am sure you are aware, it derives from the Philistines, but the geographical reference has shifted from their coastal cities. There is recent archaeological evidence that in the time of King David it was used to refer to a region further north, modern-day Lebanon. And it was used by ancient Greek writers prior to the Romans to refer to the whole region.

So in historical context, I think it is right to follow Bailey in using it to refer to geography and culture. But I agree there is an awkward clash with its contemporary reference. Perhaps it is the latter which needs to change…? It has become an ideological term without any real national or ethnic justification.

Thanks again for your own writing, which I appreciate.

I agree with Melanie on this. The toponym ‘Palestina’ was not used in the time of Christ, and certainly never as a designation for Judea, Samaria and Galilee. We don’t talk about ‘Roman England’ for good reason: it was Britannia, and the political entity called ‘England’ didn’t come till much later. Similarly with Palestina (or rather ‘Syria Palestina) – and the Roman use wasn’t neutral geography: it *did have to do with effacing Jewish-political identity, to the point of giving Jerusalem a pagan name. Further, the boundaries of ‘Palestine’ as a political entity changed repeatedly under the Byzantines, as these maps show. It is anachronistic and confusing in today’s climate to use such terms – rather like saying our seasonal friend St Nicholas of Myra was a ‘Turkish bishop’, which he wasn’t.

I forgot to enclose the link: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palestine

Brian, your comment is really odd. The Wiki page you link to says this:

The first clear use of the term Palestine to refer to the entire area between Phoenicia and Egypt was in 5th century BC Ancient Greece,[11] when Herodotus wrote of a ‘district of Syria, called Palaistinê” in The Histories, which included the Judean mountains and the Jordan Rift Valley.

I rest my case??

Herodotus referred to Palaisteine merely as the land of the Philistines, which was a small area corresponding roughly to Gaza. It did not correspond to Judea. To repeat: Jesus was born in Judea. He was not born in Gaza, and he was not born in Lebanon. The Romans renamed Judea Palestina to pretend the area belonged to the Philistines, who no longer existed, and thus tried to write the Jews out of their own history. To say therefore that Jesus was born in a Palestinian house, which was part of Palestinian culture and corresponded to the houses of present-day Palestinians is simply totally false. Where Jesus was born corresponded to Jewish housing and Jewish culture. The mendacious claim that ‘Jesus was a Palestinian’ is, as I’m sure you know, part of the Arab campaign to persuade people that the Jews of Israel are usurpers in their own country.

Melanie, I don’t think you are right there. I haven’t yet checked the Herodotus quotation, but the citation above says the opposite.

This is supported by the latest archaeological evidence as reported in Israel Today:

http://www.israeltoday.co.il/NewsItem/tabid/178/nid/25660/Default.aspx

Because of this long use of the term to refer to a region and its general culture, when I say he was in a Palestinian home, I am referring to the wider cultural context, not ethnicity or religion.

If I am wrong, you had better go back and tell the Jewish editors of the Palestine Times!

Again, I entirely agree with you that the use of the modern meaning of ‘Palestinian’ is misapplied…but that has to do with the contemporary ideology of language.

My link was to highlight the map, which shows some rather protean boundaries of Byzantine ‘Palestine’. I’ve looked up the 5 or 6 Herodotos references (in Greek) and it isn’t clear that he is referring to all the land beyond the coastal areas; it also emerges that Herodotos thought of ‘Palestine’ as part of ‘Syria’ and writing c. 450 BC he evinces no knowledge of Jews in the land – not a problem to those who think Ezra-Nehemiah late and fictional, but not easy to square with a belief in returns from the diaspora from the time of Cyrus though to Artaxerxes and beyond, to the temple-state of ‘Yehud’.

Aside from these, I can’t find any evidence that ‘Palestina’ served as a toponym before the 2nd century AD until the 19th century (by archaeologists) and certainly not as an ethnonym. As far as I know, most of the residents in the land up to the Persian conquest c. 618 were Christian Greeks; Arabization came after the Muslim conquest, and ethnic questions and identities became even more complex in the Ottoman period.

To use ‘Palestinian’ as a ‘cultural’ term for first century Galilee, Judea and Samaria is an anachronistic misnomer and not a very helpful one. Galilee was largely Jewish with Gentile villages; Judea was heavily Jewish, while Samaria was Jewish Samaritan. Tyre and Sidon seem to have been largely pagan (Acts 12).The ‘cultures’ differed significantly from place to place, to the extent that an area had been Judaized.

Brian, ‘Aside from these, I can’t find any evidence that ‘Palestina’ served as a toponym before the 2nd century AD until the 19th century (by archaeologists)’

There appears to be a list of such evidence here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_the_name_%22Palestine%22

Of particular interest are the citations of Philo, who talks of Jews inhabiting ‘Palestine and Syria’, Pliny the Elder, who sees Judea and Palestine as equivalent, and Marcus Valerus Probus, who comments ‘Judea, which is in the region of Syria Palestine.’ Josephus also talks of Jews as occupants of Palestine.

So I think there are a good number of examples, and my use stands.

I think on reflection it is more important to address the incorrect contemporary use of the term ‘Palestinian’. In current media and political discourse it is used to refer to Muslim Arabs displaced after the failure of the 1947 two-state settlement. But prior to that it was universally used to refer to anyone, of any religion or ethnicity, who lived within the geographical region. I think it would be good to get back to that until such time as there is a Palestinian state (if that ever happens).

Agreed, you have produced other examples (in a subsequent post) of pre-2nd c. usage that I wasn’t aware of – though I cannot say how accurate or widespread this usage was, and (AFAIK) it wasn’t used as a self-designation by the first century inhabitants of the land. In modern times, Palestine’ was used neutrally for the Holy Land in a geographical sense – it is there in Betjeman’s famous Christmas poem and I read it yesterday in Machen’s 1921 ‘Christianity and Liberalism’, and you find it also in titles like Sanders’ ‘Paul and Palestinian Judaism’ where it serves to distinguish from Jews in the Diaspora. But since the word has become so freighted with political meaning since c. 1965, I don’t think it is a helpful term for Biblical Studies. Geopolitical terms are notoriously slippery things: ‘Britannia meant ‘England, Wales, Southern Scotland’ until c. 400, then felt out of use until the 17th century and the Stuart dynasty. Would it make sense to talk of ‘the people of southern Britain’ in AD 500?

Again, in the political war of words of the past generation, part of Palestinian propaganda is to depict Mary and Joseph as ‘Palestinians’ who would be denied entry to Bethlehem because of the security barriers in their ‘occupied land’! Even Christian Aid and others have got onto this juvenile act – mysteriously eliding the fact that Mary and Joseph were Jews, and would morel likely face danger from Muslims today than from fellow Jews.

Thanks for the acknowledgement, Brian.

As I said just above, the problem is the politicisation of the term leading to its inaccurate use in current debate. We should not be talking of a ‘Palestinian’ state to counter the Jewish state in a two-state solution, but an ‘Arab’ state as one of two Palestinian states.

The one thing that we cannot do is re-write history in the way Melanie Philips is proposing. We need to use historical terms accurately to describe history. Mary and Joseph were indeed Palestinians: Palestinian Jews who lived in what became the Roman province of Judea.

I wonder if Melanie is also willing to agree the evidence?

And a nice illustration of the right use of the term is to note that the Jewish newspaper from the region in the Mandate era was called ‘The Palestine Times’.

That’s because the whole area – west of the Jordan and Transjordan – was called ‘Palestine’, following the suggestion of somebody with a classical education in the Foreign Office after WWI. It never had that name in Ottoman times or under Persian rule.

No but the examples I cite above show that it was a toponym in a good number of writers prior to Roman use in the second century.

Interestingly, Enoch Powell (whose Biblical scholarship was often as controversial as his politics) made a lot of these points about the stable (or lack thereof) in a piece in the The Times on 24 December 1973 entitled “No cradle at the inn”, republished in by Sheldon Press in 1977 in the collection of essays “Wrestling with the angel”.

How interesting, thanks. Did he engage much in biblical scholarship…?

Professor Powell (Prof. of Greek, University of Sydney, 1938) was a fine philologist (although not in Hebrew) and he did do some biblical research, but in a characteristically eccentric way that reminds me of Michael Goulder. One of Powell’s conclusions, IIRC, is that Jesus wasn’t actually crucified. This apparently didn’t stop him being an Anglican in good stead. Who said we’re not a broad church?

Enoch contra mundum: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/christ-was-not-crucified-says-enoch-powell-1383775.html

I love the Catholic comment: ‘If Mr Powell is right, we’ll have to make a lot of changes to church architecture.’

Fascinating life. Full Professor aged 25…but influenced by Nietzche

His complaint was: ‘Nietzsche beat me’ (as he was a full professor at 24). Powell did a lot of other astonishing things in his life, including resigning his professorship to enlist as a private at the outbreak of war, in the course of which he became a brigadier, to say nothing of his colourful political career as MP from both sides of the Irish Sea and sometime Minister of Health. A man impossible to pigeonhole.

It looks like a few people have already answered this question, but here’s a few points.

As one or two people have said, Powell was Greek scholar, and his analysis of the Bible was based on his knowledge of the languages in which it was written. He was very good, therefore, at spotting where the Gospels had been rewritten, had extra bits added, or had multiple authors. The big criticism of him as a Biblical scholar was that linguistics was his only technique – he knew relatively little of the history and context of the texts. This may be how he felt able to “prove” Jesus wasn’t crucified.

The whole issue of Powell’s religion is fascinating. It’s very possible that his Anglicanism was more nationalistic than religious – an allegiance to the national church. He also argued very Strongly against the use of Christianity to back up liberal or socialist ideas. To him, Christianity was about the salvation of the soul and had no social message. He had run-ins with Paul Oestreicher and Trevor Huddleston on this issue. His ideas about religion and society are set up in 2 volumes of essays “No easy answers” and “Wrestling with the angel”, both out of print but sometimes popping up second-hand on Amazon.

Andrew, this ‘He was very good, therefore, at spotting where the Gospels had been rewritten, had extra bits added, or had multiple authors’ is predicated on an unrealistic (and untested) assumption in critical (= liberal protestant) scholarship of a certain assumption of consistency within an author which has been seriously questioned in recent years.

There has been a significant shift in scholarship generally to seeing the gospels as written earlier, by single authors, believed by some to be based on eyewitness testimony.

Stylometric computer analysis, similar to that used in anti-plagiarism software, in general confirms this.

Thanks for that, Ian. Are there are accessible books on this new thinking?

Meanwhile, millions upon millions of people are still living their whole lives and dying in utter ignorance of Christ, and the fundamental points of the gospel.

But fear not: in the West, evangelical theologians really are going to apply their energies to that problem, just as soon as they can work out exactly what breed of donkey carried the Saviour into Jerusalem. Several learned articles with many erudite footnotes are being penned on this subject as we speak.

David, I wonder if you could say something that justifies your cynicism here.

As I show in the related posts, I used this work as background to my preaching at our Carol Services, where we had more than 800 people attending, many of them visitors. We invited them to find out more for themselves by coming to our Alpha course.

Why do you think clear thinking has nothing to do with faithful witness?

When thousands of people descended from David converge on Bethlehem, I think it is quite probably that there might have been no room any place for Mary and Joseph to stay.

Where do you get the ‘thousands’? My understanding was that the population of Bethlehem was probably around 200 at the time.

Besides, this is all speculation. Luke says nothing about this, or in fact about Jesus being rejected at all. The consistent theme of Luke 2 is his reception and acclamation.

And there were probably a goodly number of Roman and Judean officials there also to administer the census correctly. They got first dibs on the good rooms you can bet.

Really? How many would it need? A centurion with a small troop was enough to subdue an area like Galilee.

Maybe not as Jews can’t accept heathen gentiles in their homes or residential grounds. Even a centurion told Jesus was not required to come to his residence as he was knowledgeable enough that a rabbi is ritually clean and can’t be unclean by entering a Gentile’s house or touching his stuff.

I am far from a theology scholar, and there are some very educated folks in this thread and thus I hesitate to even weigh in, but I did enjoy learning about this, and it triggered a good conversation on my Facebook wall. Knowing the people we know from that part of the world, we collectively agreed it was unlikely they would be left to fend or themselves. My people show up with food, and I like to believe that was already the case then.

I read a great (I thought, anyway) piece by Joe Kay recently entitled “Why are Manger Scenes So Weird” which was kind of from the opposite direction; why does our imagery show the Holy Family so calm and composed, considering that what little we know about their lives suggest they were anything but glamorous? Since we have (and take) great liberty to “see” them as we wish, why would we want to “make” our Savior less like us, and thus harder with whom to identify?

I riffed off that to the religious visuals of my 1970s Roman Catholic upbringing, and why we persist, as someone mentioned above, in portraying people from the Bible as Nordic-looking? 7th century painters who didn’t travel had an excuse, but why, in the age of historical scholarship and discourse like is happening here, do we still have “Surfer Jesus”?

My thoughts at http://vergeofjordan.blogspot.com/2014/12/sleep-in-heavenly-peace.html

Thanks Chris. yes, I think the question ‘why are manger scenes so weird?’ is a really good one. They appear to have little connection with the realities of life then or now…which I have come to see (through this little controversy) is really important.

Watching a classic nativity play rarely changes anyone’s life…

I can see that this might be an interesting point if you’re interested in what “Luke” (whoever he was) meant by what he wrote. But surely you don’t think that any of this actually happened. I’m not disputing that Jesus might have existed and that assuming for a moment that he did he was obviously born somewhere, the question is whether Matthew and Luke knew any of the details, and their stories are so contradictory and historically impossible that this is unlikely.

To me this is all as absurd as discussing the details of the Cindarella story as if that actually happened.

‘But surely you don’t think that any of this actually happened.’ Yes, as it happens I do.

Luke is a first-rate historian by first century standards. You can see discussion on another post of mine which compares him with Josephus in terms of consistency and coherence.

If you want to write off Luke as a historical record of value, then you are going to have to ditch just about every historical record from the ancient world first. So your conclusion would be ‘We know nothing about the historical past.’

http://www.psephizo.com/biblical-studies/did-luke-get-the-date-of-jesus-birth-wrong/

This argument that Luke is a reliable historian is one I often hear from apologists, but I usually hear the opposite from less biased biblical historians and new testament scholars, amongst who there seems fairly wide concensus that the nativity stories in both Luke and Matthew have very little historical value.

After all, if you consider Luke reliable about the nativity you have to consider Matthew unreliable since the two are so contradictory. And lets not forget the basic 10 year discrepancy between them, with Luke placing the census in 6 AD

Jimmy, I don’t agree with you here, and set out the reasons in some detail in the post I link to in the comment above.

The comparison between Luke and Josephus in terms of consistency does not put Josephus in good light. See particular the work of historian Shaye Cohen.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shaye_J._D._Cohen

Ian, thanks for your reply. The difficulty for me, as a non believer but someone who is interested in knowing where the truth lies behind these stories, is who to rely on. I want to be able to rely on well regarded historians and biblical scholars and not apologists. The article you linked to above is interesting and I’m pleased to see that you don’t use some of the standard apologetics to avoid the genuine issues with the census. But there is still very much an apologetical whiff about it all. For example you give instances where you say Luke has subsequently been verified, but I believe that there are also many instances where Luke can be shown to be just plain wrong.

My understanding is that it is becoming more widely thought that Luke in fact used Josephus as a source. Given that we know he used Mark and possibly Matthew (depending on your view of Q) this doesn’t seem unlikely.

Can you point out the ‘plain wrong’ things?

When we are comparing a historical document with other historical evidence, we always need to weigh one against the other. There are some good examples where Luke was thought to eb ‘plain wrong’ and later proved to be correct.

With Josephus, there are a good number of internal contradictions in his work (which I don’t think anyone argues for Luke) and other things which are just plain impossible—but make great reading.

See Shaye Cohen on Massada and Josephus

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/religion/portrait/masada.html

Ian, even if one is inclined to accept that the both infancy narratives are essential myths, your analysis of the content of Luke”s “myth” retains its significance. For the “myth” was intended by the author to have meaning, and the first step in divining any author’s deeper meaning is the superficial meaning of the words as understood by the original writer and readers.

(I confess I have yet to read you consideration of Luke’s historicity–that’s next.)

Thanks Dennis—yes, I agree with you. The basic discipline of reading is to do your exegesis well, whatever hermeneutical context you then put that in.

Ian, my email version of your reply contains the following addition:

“You can see more information for the comment on this post here:

http://bit.ly/1wBo4KY/comment-page-1/#comment-329291”

But that link takes me to an error page.

I’m intrigued, and it occurs to me this error may be of interest to you.

‘We know nothing about the historical past’.

I had my five minutes of fame in April this year when my marriage was reported widely in the press and on the internet. I married in a register office, in Nottinghamshire, in the morning. Despite the modern technology of instant communication, digital photography and all the rest of it, within days that same wedding was being reported as having taken place in a hotel in Lincolnshire, in the afternoon!

I only studied history to ‘A’ level but one thing I did learn is that the notion of ‘historical truth’ is a chimera.

I suspect we have all been subject to this kind of misreporting—but what does it tell us? That all reporting is false? That the motives and methods of Luke are the same as the contemporary tabloid press?

If ‘historical truth’ is a chimera, then are you happy to deny e.g. that Wellington defeated Napoleon at Waterloo? That the Shoa never happened? That there was no Christmas Day Truce in 1914?

Or that all these assertions are simply untestable? If so, then I think we are all trapped in an eternal (and rather meaningless) present.

My point was that the timing of, location of, and type of building in which the birth of Jesus took place is perhaps something that may never (cannot ever?) be known with any accuracy. Note that I am not denying here that the birth of a person called Jesus happened at all, rather, I am commenting upon the accuracy of subsidiary details of the type your original piece was exploring.

Regarding motivations, in the personal example I gave, there was no apparent motivation behind the mistakes which quickly crept into the reporting – the usual ones of sex, money, fear and power being absent in the misreporting of minor details, whatever other biases might have existed in the story. It was simply people getting the facts wrong – not unlike when one plays the party game of Chinese Whispers. I can’t see why the narratives surrounding the birth of Jesus should be exempt from such human error.

What about the rules of separation for a child bearing mother and consequent days after birth as termed ritually unclean?

Consider the generations of scripture following Jews who have carefully constructed their lives for following rules that do not break the rule of the law. That is like an outer balloon covering an inner balloon. If you break the outer balloon there is every chance of breaking the inner balloon. For this way of thinking to be over zealous, Jesus said of the religious type that they follow their traditions rather than God not even using their little finger to help.

Definitely Joseph and Mary faced a difficult task of convincing anyone to allow themselves and their house or inn or upper rooms to be ritually unclean for the cause of child delivery. Think of a person walking for a day or 5 days or a week (depending on the days towards purity) “I am unclean” so that no one else would be unclean by touch. So a known ritual uncleanness incident like for a child bearing woman (9 months) and then 60/90 days after delivery requires preparation. Consider the complication if the child or mother dies in the process of delivery, the emotional toll goes higher on dealing with dead body in the house and people become ritually unclean when touching them too. There is a high possibility that Joseph and Mary accepting an isolated place due to this as no one wanted to be unclean. Else the narrative would have cited Joseph’s distant relative in the ancestral home town had a place for them.

Another angle to refute the above consideration of the birth in a house, if theologians consider Jews (in Jesus time) like poor farmer community. Queen Sheba was impressed with King Solomon’s arrangement to everything, servants, food etc a kind of fashionable royalist that could have started a trend as the news spread. Even the concept of precut stones made from another location that would be assembled at site in building the temple.

After so many years, would not Israelis learn to construct residential towns without having stables over or under their houses? Was everyone of the same social strata that they slept with their animals in the house?

A poor farmer’s house does not have to be demolished during war or famine and can survive to an archaeological find of our time. This cannot be considered the standard model of every house in Israel. Knowledge of trap doors, false floors to hid anyone or wealth is known and possibility that the victor has to destroy all well to do houses to find it out. Prophet Ezekiel was shown in a vision to see under an elder’s house as a group of prominent people was coming to do idol worship in secret.

Luke 2:12 says the angel said go to the manger to find a baby wrapped in cloths. The only baby that night and no reference to anyone’s house. Was the angel not knowledgeable enough? Acts 10:32 angel actually tells how to identify the person and house.

Funny you should mention that—I’ve been reflecting on it. The angel appears to be saying ‘You won’t find anything out of the ordinary’.

Exactly. It would not be difficult to identify the manger in this case when inquiry is made considering the situation that this couple is in. It would be easy to know from such a small population which household was prepared for ritual uncleanness and new found happiness in the news of a male child birth. Rather it was out of norms and identified that a couple had to occupy a manger for the purpose.

The country side rearing shepherds were not natives of Bethlehem town, and were told by the angel specifically which town to look into.

And in between or about two years time, the couple moved into a house by then. As when the wise men made it to Bethlehem the child (not a baby) was with the mother in a house.

Are you aware that this blog post was reported on the website of the Guardian, and subsequently posted on its Facebook page? According to one person commenting there, you sir, I am afraid to say, are an “anti-Christian, hate filled, bigot”, and that is not untypical of the level of comment there from people who presumably consider themselves true christian believers.

I am not a christian myself, and personally do not believe that the gospels are at all historical, and can not believe for one minute that there could ever have been a census requiring the entire population of the Roman empire to return to their home towns. The very idea is ludicrous.

Yes, I was aware of this, and the article is also in the Independent and Mail online.

I don’t make any presumption about people calling me such names—I think it is testimony to their own ignorance, and nothing much beyond that.

I am not sure why you would think the Romans relocating people unbelievable. Luke is (by any analysis) a much more reliable historian than other contemporary writers we have—though in fact our certain knowledge of such events is sketchy at best.

To my knowledge, we have no reliable testimony of e.g. Hannibal crossing the Alps.

I think the extensive and blatant use of midrash in the gospels to artificially construct biographical details and events using scriptural quotations is a complete game changer in the way we have to see the origins of christianity and the nature of those gospels.

A census would be undertaken for the purpose of taxation, and hence would not require the movement of people across the empire to their places of origin. Imagine the impact of such a thing being done today within the EU, for example. It would not only be pointless, but socially and economically catastrophic. Absurd in the extreme.

We don’t have proof on how tax head count was done during roman rule and how many times it was modified to suit the situation.

Consider the way Joseph travels when faced with his situations. He takes up a new residence with each situation. Which shows he did not have land or sold what he has to buy at another location. So Joseph made the travel when tax registration was required. If he made the travel leaving his wife behind, he could be piling debit in the residence they were currently staying as he was the (possible) daily wage worker. Also shows he was a man without extended family members to shelter his wife under their care.

But what about bill for tax paid? Look at the answer Jesus gives to Peter when tax collectors came to Peter’s mother-in-laws house – pay for both of us. This was Galilee. So during the last 30 yrs new implementation brought some form of uniformity in tax collection and accounting that it was not a gospel necessity to mention how the proof of tax payment was established at such various points of time.

You are overlooking the fact that the narrative concerning Joseph’s travels is constructed to take in various bits of scripture which the author wanted to weave in for religious reasons. Hence the messiah would be born in Bethlehem, he would be called a Nazarene, Rama weeping for her children, I called my son out of Egypt etc. The same applies to the passion narrative, based upon Isiah’s suffering servant. Once you appreciate this it becomes impossible to take seriously any attempt to establish historical veracity.

But Peter, that is just the point. Apart from your first example, with a reference to Bethlehem, the other three are just nonsense when taken as the meaning of the OT.

. The ‘Nazarene’ text is a very mangled extract from the story of Samson, and is about hair, and has nothing (in its OT context) to do with Nazareth.

. Rama weeping is from Jeremiah, and again was not a messianic text

. As I mention below, Hos 11 again was not a messianic text, and referred to the past, the Exodus, and not the future.

If anything is going on here, it is Matthew badly mangling texts to fit the story, and not a fitting of the story to the texts. It is the use of Scripture which is a real problem for evangelicals like me, not the use of history.

Peter, I think the use of midrash has the opposite significance to the one you suggest.

If you are needing to make events fit a literal reading, then when they don’t fit, you (in effect) have to change the events.

But if the meaning and reference of a text is hermeneutically malleable, then in fact you do not need to change the details of the events—you can simply re-read the original text in such a way as to fit them. We see a really good example of this in Matthew’s use of Hos 11 ‘Out of Egypt I called my son.’ The fact that no-one thought of this as a messianic text means that Matthew did not invent the flight to Egypt, but rather, knowing of it, went and looked for a text to connect with it.

If the use of OT was more straightforward, *that* would be an indication of the unreliability of the historical record.

I found your article informative, and interesting. Most refreshing was your unbiased approach to defining the language of the scriptures. I have studied Biblical Hebrew for decades now, and found it fascinating to see the parallels of Biblical Greek and Hebrew. “Kataluo meaning to unloose or untie, that is, to unsaddle one’s horses and untie one’s pack”. If you apply concrete Hebraic thinking to this, the word describes exactly what happens when your reach your destination. Loose or untie……stop traveling. As you candidly point out this doesn’t necessarily mean arrival at a stable.

I teach Biblical Hebrew, and Salvation history as a general Bible study to small groups it’s always amazing to see the reaction of people when the actual definitions of words are explained, lots of head shaking, and critical looks about the room. People don’t like having their presuppositions shattered. Which is unfortunate since the Bible is fascinating to learn in the original languages since so much depth is lost in translation.

Will, thanks. Every blessing on your teaching ministry!

Your article is outstanding and gratefully received, as is Carlson’s work. I’ve been aware of this issue for many years but still took away some new insights. Two years ago a fellow minister and I co-wrote an article on this subject for The Good News magazine published by the United Church of God, quoting from Bailey and others. You might appreciate it (at http://www.ucg.org/jesus-christ/was-there-really-no-room-inn/).

Ian, I have preached this and lived to tell about it!

I appreciate the point about Jesus coming to be with and like us.

One point I stress is that, contrary to the traditional line of Jesus being born in a stable to demonstrate humility, His being born is in itself the most humble aspect of the narrative.

Aside from the virgin birth, He was just like us, yet without sin.

That’s great. Glad you lived to tell the tale!

I can see the argument about the exact nature of a ‘stable’ in first century Palestine and the meaning of kataluma but I am incline to say ‘So what?’ Someone passed me this article before Christmas and seemed to expect it to change my preaching – it didn’t. OK I was tried to avoid direct reference to a stable but as I say, so what?

The crucial question that this article does not seem to deal with is how the phrase ‘ouch en autois topos’ – ‘there was no room’ – fits into the narrative that Luke is developing. Why does Luke include it?

Luke is not trying to teach us about the living arrangements in first century Bethlehem, he is unfolding the story of God’s amazing action in history through the incarnation.

The story so far is a glorious roller coaster of God’s intervention and people saying ‘yes’ (albeit with a bit of a hiccup with Zechariah) and praising God. So the phrase ‘there was no room’ sticks out and jars the story, there will be opposition later but Luke appears to be making the point that it started here. Yes, the phrase jars, and I can see why Luke has done it. If this phrase is about the living arrangements of a busy household then it jars even more but I am left asking ‘why on earth has Luke allowed himself to be distracted by an irrelevant detail?’

You say ‘… it would be unthinkable that Joseph, returning to his place of ancestral origins, would not have been received by family members’. Why? The story that appears in John 8 (the woman caught in adultery) indicates what many of Joseph’s contemporaries thought should happen to women like Mary; by agreeing to marry her he would be bringing disgrace on his family as much as she did on hers. He would therefore very likely have been ostracised by his family.

In your reply to Tricia you say ‘… I am struck by the fact that Matthew’s account, written consistently from a male perspective, includes this as a problem. By contrast, Luke’s account, written from the women’s perspective, does not mention this as an issue, and instead focuses on the miraculous nature of the conception.’

Again this is unconvincing. Luke does not write from ‘a woman’s perspective’ – he does not include distinctively feminine insights. Rather he writes as an apologist for women having key roles in the unfolding narrative of the incarnation. So, for example, there is no distinctive feminine style in the ‘Magnificat’ in contrast to the ‘Nunc Dimittis’ or ‘Benedictus’, all are glorious hymns of praise. What is distinctive about Luke is that he gives such words to a woman.

So you reply to Tricia, ‘Luke’s account, written from the women’s perspective, does not mention [that Mary may not have been welcome because of her pregnancy] as an issue, and instead focuses on the miraculous nature of the conception.’

But, reading the account acknowledging Luke’s apologetic position does this stand up? Arguably Luke is saying precisely that Mary (and Joseph) were unwelcome because of Mary’s pregnancy. However what Luke is doing is writing the story so that it reflects badly on Joseph and his family rather than Mary and hers. I am inclined to go further (though I do appreciate that this is, to a large extent, an argument from silence and therefore to be treated with caution). I think that Luke actually does allude to Mary being ostracised, but only by implication. Why are Mary’s family in Nazareth not mentioned? Why is the first thing that she does having found out that she is pregnant to leave home? Why is the only person that she confides in a woman who is herself miraculously pregnant?

Is Luke alluding to problems for Mary at home in Nazareth?

No, re-reading Luke’s account I remain convinced that the power of the phrase ‘ouch en autois topos’ – ‘there was no room’ is precisely that Mary and Joseph were ostracised in Bethlehem. Discussion about the exact meaning of words frequently translated as ‘inn’ or ‘stable’ seem interesting but do not appear significantly to change the power of Luke’s narrative here … unless I have missed something?

(PS – sorry it has taken a while to reply, I’m only just getting going again after a rather hectic Christmas!)