James Bejon writes: As Christians, most of us are familiar with harmonised versions of the NT’s birth narratives. We see them acted out each year in Nativity plays (if we subject ourselves to such things). Considered in isolation, however, the birth narratives are less familiar, and even slightly awkward. They gloss over major events. Or, to put the point another way, they don’t mention what we might (reasonably?) expect them to mention. Consequently, most critical commentators dismiss (elements of) them as ahistorical. If Joseph had really fled to Egypt to avoid a massacre, we’re told, Matthew wouldn’t be the only person to mention it. And if Joseph had really ended up in Bethlehem as a result of an empire-wide census, Luke wouldn’t be the only person to mention it. And so it goes on.

But how can such commentators be so sure they know what Matthew and Luke—individuals about whom they can tell us very little—would have wanted to include in their narratives? If their narratives aren’t inherently incompatible (as I’ve sought to show here), and if we can provide plausible reasons why Matthew and Luke might not have wanted to mention the particular incidents they decline to mention, then why should we think their narratives are ahistorical, even in part?

Here, I want to consider whether such reasons can be provided. The hypothesis I’ll advance is as follows. Jesus was born in tumultuous times. The events of his birth included a census, a massacre, a flight to Egypt, and many other things besides, and Matthew and Luke took these events to be significant—i.e., to frame Jesus as the fulfilment of Biblical history—but each writer focused on different aspects of them. For Matthew, Jesus is a Moses-like deliverer, who presents an immediate threat to the world’s Herods. As far as Matthew is concerned, then, Jesus’ presentation at the Temple and childhood in Nazareth are irrelevant, and to include them would be a distraction. Meanwhile, for Luke, Jesus is a more subversive and Samuel-like figure, who grows up and in around the Temple. From Luke’s perspective, then, Jesus’ stay in Bethlehem (after his presentation at the Temple) and flight to Egypt are irrelevant, while his presentation at the Temple and (undramatic) childhood are highly relevant.

That Matthew and Luke don’t write the way we might expect is, therefore, quite true, but it’s evidence not of their ahistoricity, but of the purpose and sophistication of their narratives (not to mention the climactic nature of their Messiah’s entrance into world history). If, by today’s standards, that makes elements of their narratives ahistorical, then it makes elements of their narratives ahistorical. But trustworthiness and conformity to (modern-day) expectations are two different things. Ultimately, if we want to engage with Matthew and Luke in a fruitful way, we need to engage with them on their own terms rather than on the basis of our expectations.

What are the issues?

The best known critical commentary on the NT’s birth narratives is Raymond Brown’s The Birth of the Messiah. It was written over the course of over fifteen years, consists of some 750 pages, and is representative of a much wider body of scholarship. At the conclusion of the book’s introduction, Brown dismisses many elements of the birth narratives as ahistorical. If the census had really taken place, he says, Matthew would have mentioned it as well as Luke. And, if the flight to Egypt had really taken place, Luke would have mentioned it as well as Matthew. And even if the massacre did take place and Luke didn’t mention it, it would be reflected elsewhere in the NT. And so it goes on. Below, we’ll consider the specific details of Matthew and Luke’s narratives and see if we agree with Brown’s assessment of them. (Note: Brown also identifies other issues with the birth narratives, but for now we’ll restrict our discussion to the issue of their internal plausibility.

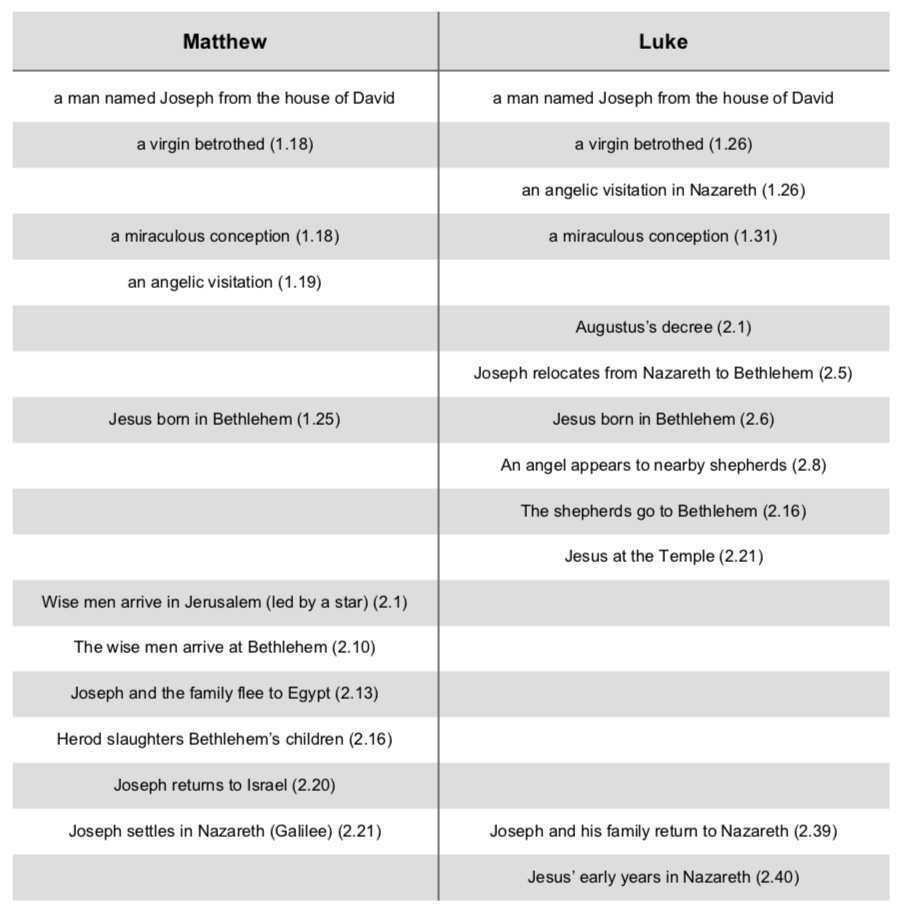

As I’ve tried to show elsewhere, Matthew and Luke’s narratives are predicated on a common core of events. Both narratives open with a description of a couple who are engaged to be married, namely Mary and Joseph. Both identify Joseph as a man of Davidic descent. Both have Mary conceive by the agency of the Holy Spirit. And both have Jesus born in Bethlehem and subsequently raised in Nazareth.

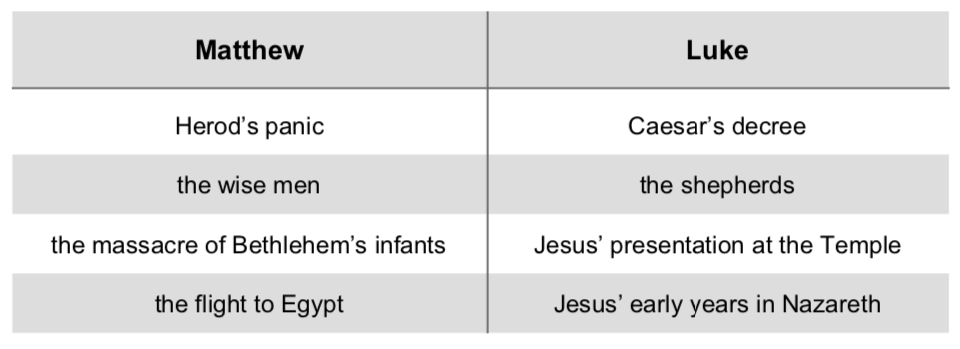

Nevertheless, Matthew and Luke’s narratives differ in some important respects. Whereas Matthew tells us about Herod, the wise men, the massacre at Bethlehem, and the flight to Egypt, Luke tells us about a different set of events altogether—events which involve Caesar, the shepherds, Jesus’ presentation at the Temple, and Jesus’ childhood in Nazareth. They line up in this way:

Matthew and Luke’s narratives thus frame Jesus’ early years against quite different backdrops, which has led many commentators to question the historicity of Matthew and Luke’s narratives. If Luke was a competent historian, wouldn’t he have been aware of the massacre of Bethlehem’s infants? And, if he was aware of it, why didn’t he mention it? Why does Luke instead have the family head back to Nazareth, with no mention of Joseph’s flight to Egypt? And why, if Luke’s narrative is reliable, doesn’t Matthew mention Caesar’s decree and/or the shepherds? Is it credible to think Matthew was aware of the events recorded in Luke’s narrative and yet declined to mention them (and vice-versa in Luke’s case)?

That all depends on how and why we think the Gospels were composed. If we think Matthew’s aim was to find out as much information as he could about Jesus and then write it all down in a gospel, Matthew’s failure to mention certain events does indeed seem problematic (and likewise in Luke’s case). Very few people, however, think that’s what the gospel-writers did, and for good reason. Consider, for instance, Matthew and Luke’s genealogies. Matthew and Luke were familiar with the OT. Matthew therefore had names available to him which he chose not to include in his genealogy, and Luke had a whole ancestral line (from Shealtiel to David) available to him which he chose not to include in his genealogy (compare 1 Chron 3). More radically, consider the Gospel of John. Do we think John was unaware of the things he didn’t mention in his gospel (e.g., Jesus’ temptations, parables, exorcisms, transfiguration, and institution of the Lord’s supper)?

Like all authors, Matthew and Luke wrote with specific purposes in mind. Each man wanted to tell Jesus’ story in his own way—to highlight particular themes of Jesus’ ministry, to emphasise particular parallels between Jesus’ ministry and OT history, and so on. And if we pay attention to how they did so, it will help us make sense of their selection of material.

Matthew

So, what are the specific purposes of Matthew and Luke’s birth narratives? We’ll start with Matthew’s. Its distinctives can be summarised as follows.

Spelt out more fully: while Luke tells us about Caesar and the census, Matthew tells us about Herod and the massacre of the infants. While Luke tells us about the shepherds, Matthew tells us about the (star-struck) wise men and their gifts. And, while Luke has Jesus at the Temple and/or Nazareth, Matthew has Jesus’ family flee to Egypt.

Now, why has Matthew chosen to tell us about these events in particular (rather than those described by Luke)? What’s their common theme/connection? The answer, I suggest, is that they’re all distinctly exodus-shaped events, which portray Jesus’ birth as a sign of an exodus to come.

Consider some of the relevant parallels. Both stories open with Israel ruled by a foreign overlord (in one case an Egyptian, in the other an Edomite). Both revolve around the birth of a child who’s destined to deliver his people. In both cases, the overlord in question views the child as a threat (cp. Exod. 1.9–10). Both stories have the overlord massacre Israel’s infants in an attempt to secure his position. In both stories, God’s deliverer flees to a foreign land, where he holes out until his enemies have passed away (cp. Matt. 2.20 w. Exod. 4.19). In both stories, God outwits (ἐμπαίζω) his enemies (cp. Matt. 2.16 w. Exod. 10.2). And, in both stories, God’s people are made rich by the Gentiles (cp. Egypt’s wealth w. the wise men’s gifts).

These parallels are no coincidence. Indeed, in Matt. 2.15, Matthew explains the significance of Joseph’s sojourn in Egypt by the citation of Hosea 11.1: ‘Out of Egypt I called my son’. Just as God began a redemptive work in Moses’ day when he called Israel forth from Egypt, so in Joseph’s day God will again call his Son forth from Egypt and begin an even greater redemptive work.

Matthew’s allusions to the exodus, however, aren’t simply a vague anticipation of redemption. They outline a deliberately inverted exodus story. Everything is back to front. The murderous king isn’t an Egyptian Pharaoh, but a ‘king of the Jews’. The land in which God’s son is imperilled isn’t Egypt, but Israel. And the land where the son is accepted isn’t Israel, but Egypt. Why? Because Jesus’ exodus won’t simply be a rerun of the original; it will be a different kind of exodus. The line of division between God’s people and God’s enemies won’t be drawn on the basis of nationality (Israel vs. Egypt: Matt. 8.11–12, 10.34–39), but on the basis of obedience (12.46–50). And, on the night of the Passover to come, God’s firstborn Son won’t escape death.

The relevance of Matthew’s genealogy

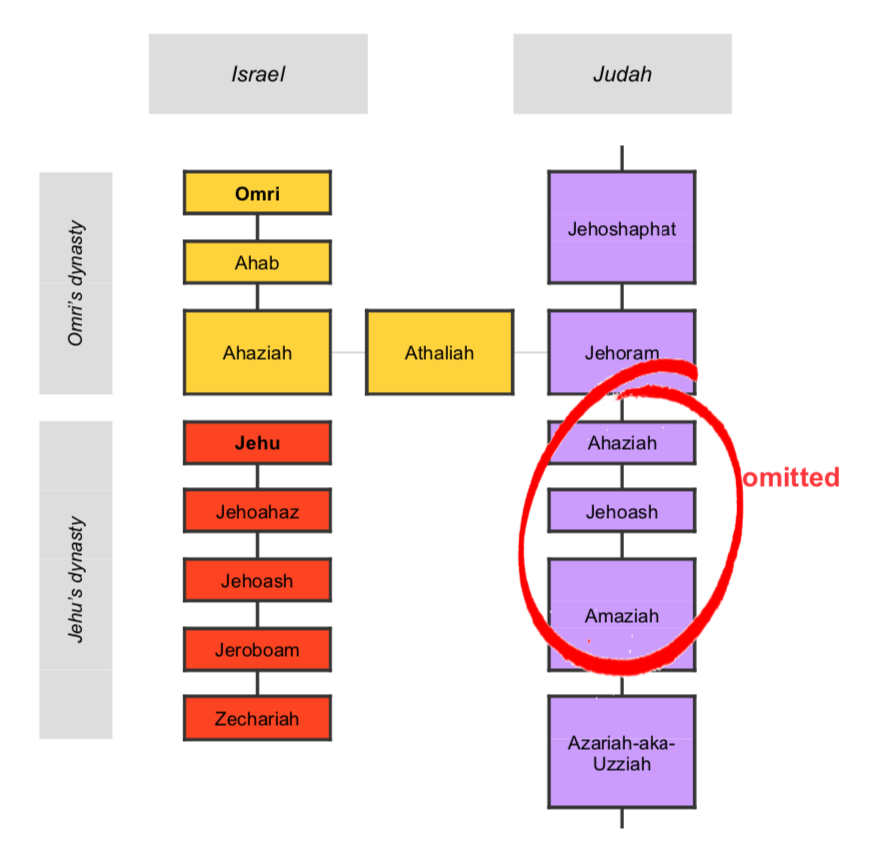

That Matthew’s allusions to the exodus are intentional is confirmed by their echoes in Matthew’s genealogy. Consider, for a start, the notion of a foreign ruler who massacres a host of infants in Israel. Matthew’s genealogy also draws our attention to such a ruler, which it does by means of a conspicuous lacuna in its king list.

Suppose I tell you I spent last Christmas with my mum, my brothers, and my sisters. While my statement is ostensibly about my mum, brothers, and sisters, it draws most attention (somewhat paradoxically) to my dad, since it makes you wonder why I haven’t mentioned him.

Matthew’s genealogy works in a similar way. After Jehoram-aka-Joram, the next king mentioned in Matthew’s genealogy is Jehoram’s great-great-grandson (Azariah-aka-Uzziah). Matthew thus fails to mention three Judahite kings: Ahaziah, Joash, and Amaziah.

Why does Matthew omit these three kings? Part of the answer, I suggest, is to draw our attention to a notable sequence of events which transpired in their days. The accession of Ahaziah was a notable event in and of itself, since Ahaziah was the son of Jehoram and Athaliah, and Athaliah was a daughter of the recently-cursed Ahab (2 Kgs. 8.16–18, 25–26). Ahaziah thus represented an unwelcome injection of foreign blood (and behaviour) into David’s line (cp. 2 Chr. 21.13 w. the refs. to Ahab’s influence in 22.1–6). And, a year later, an even more notable event took place: Ahaziah died without any sons old enough to succeed him, at which point Athaliah sought to slay all the potential heirs to the throne and claim it for herself.

Mercifully, however, Ahaziah’s sister managed to spare Ahaziah’s youngest son, Joash, and hide him away (protected by a Gentile guard) until he was old enough to reign (cp. 2 Chr. 22–23).

Consider, then, the situation. We have a foreign ruler in charge of Israel (i.e., an illegitimate ‘king of the Jews’), a newborn child who’s a threat to the ruler’s authority, an attempt to extinguish the ‘line of promise’, and a member of royal family who’s hidden the child away in a foreign environment. Ring any bells? It should do. It’s another exodus event.

Matthew’s king list thus fulfils at least two important functions. First, it underscores the unity of theme of Matthew’s narrative. And, second, it underscores the threat presented by Jesus. Jesus is a legitimate heir to the throne of David, born in the right place at the right time (Matt. 2.3–6), which is why Herod has to eliminate him.

The riches of the Gentiles

A final exodus-like feature of Matthew’s genealogy can be identified in its allusions to the riches of the Gentiles. Its fourteen-fold periodicity highlights four individuals—Abraham, David, Jechoniah, and Jesus—all of whom receive considerable help and riches from Gentile rulers/nations. Abraham emerges from Egypt not only unscathed, but enriched by the land’s silver and gold (Gen. 12.10–13.2). David finds (temporary) refuge among the Philistines and is given silver and gold by Gentile kings (2 Sam. 8.10) (as is his son, Solomon). Jechoniah is shown special favour by the king of Babylon (2 Kgs. 25.27–30), as is his son (Zerubbabel), who emerges from Babylon with silver and gold (Ezra 1–2). And, as we’ve seen, Jesus himself is preserved in a Gentile land and made rich by gifts from foreign lands (compare Exod. 3.22, 11.2, 12.35).

Reflections on Matthew’s narrative

In sum, then, Matthew’s birth narrative is a careful and sophisticated composition, tied together by a clear unity of theme. True, that doesn’t make Matthew’s narrative historical, but it does help to explain Matthew’s selection of material. In the view of many commentators, Matthew and Luke’s birth narratives can’t both be historically accurate because Matthew shows no awareness of Luke’s census or Joseph’s journey to Bethlehem. How, then, do such commentators think Matthew’s narrative should have been written? Well, suppose we rewrite it like this:

And so all the generations from Abraham to David were fourteen generations, and from David to the deportation to Babylon fourteen generations, and from the deportation to Babylon to the Christ fourteen generations.

Now, the birth of Jesus Christ took place in this way: when his mother Mary had been betrothed to Joseph, before they came together she was found to be with child from the Holy Spirit. And, at about that time, a decree went out from Caesar Augustus that all the world should be registered, which was the first registration when Quirinius was governor of Syria. And all went to be registered, each to his own town…

Matthew’s narrative is now more consistent with Luke’s, right? By the same token, however, it’s far less lucid. As we’ve seen, Matthew’s genealogy is crafted in such a way as to anticipate Herod’s hostility, and Matthew’s citation of Hosea explicitly frames Herod and Jesus’ encounter in light of the exodus. Caesar’s involvement in the matter is, therefore, irrelevant to Matthew. Caesar didn’t occupy the throne of David, nor did he see Jesus as a threat, nor did his decree cause Jesus to flee to a foreign land. (Indeed, unlike Herod’s, Caesar’s decree is conducive to the fulfilment of God’s purposes.) Consequently, a description of Caesar’s involvement in Jesus’ birth would only dilute and confuse Matthew’s narrative. And, as we’ll now see, the same is true of Luke’s (mutatis mutandis).

Luke: The Temple rather than the palace

Matthew and Luke’s birth narratives portray Jesus in quite different ways. For Matthew, Jesus is a Davidic king, who presents a threat to Israel’s rulers from the moment of his birth. For Luke, however, Jesus is man of more humble origins. Jesus is no threat to Caesar (as yet) and is more closely associated with the Temple and priesthood than with the throne.

Spelt out more fully:

- Whereas Matthew’s Gospel opens with an announcement of Jesus’ status as the long-awaited son of David (1.1), Luke’s opens with a story about the struggles of a little-known priestly couple and their duties at the Temple.

- Whereas Matthew’s genealogy is headed up by two of the best known figures in Jewish history (Abraham and David) (1.1), Luke’s begins in obscurity and works its way upwards to David and Abraham—a direction of travel elsewhere associated with priestly genealogies (cp. 1 Chr. 6.31–48 w. its context).

- Whereas Matthew’s narrative begins in Bethlehem, Luke’s begins in the Judean hill-country and later relocates to Nazareth—a town of little significance in OT history (John 1.46).

- Whereas Matthew’s Messiah is born king of the Jews (Matt. 2.2), Luke’s begins his ministry at the age of thirty (as all priests do).

- Whereas Matthew’s birth narrative culminates in the declaration ‘The kingdom of heaven is at hand!’ (Matt. 3.1–2), Luke’s culminates in a description of Jesus’ worship at the Temple (and submission to his parents).

- And, whereas Matthew has Jesus offered ‘the kingdoms of the world’ at the conclusion of his temptations, Luke has Jesus brought to the Temple, which is where his Gospel ultimately winds up.

Matthew and Luke thus present Jesus in different ways, though they do so for similar reasons. Just as the distinctives of Matthew’s narrative are intended to frame it against a particular OT backdrop (the exodus), so too are those of Luke’s narrative.

Consider the picture Luke paints for us. We have a priestly couple who are unable to have children, a misunderstood woman whose prayer is finally answered, the birth of a child, a woman who responds in songs of joy, a couple who go up to the house of God each year to worship, and a young boy left at the Temple, where he astounds his seniors with his wisdom, all set against the backdrop of the tenure of two ungodly priests (Annas and Caiaphas) (3.2).

Why has Luke chosen to describe these states of affairs in particular? Are they tied together by a common theme? They are indeed. They’re a recapitulation of a previous birth narrative in the Biblical narrative, namely Samuel’s (1 Sam. 1–2). For Luke, Jesus’ birth doesn’t signal the arrival of a Moses-like leader, but of a Samuel-like servant—a boy who may not be an immediate threat to men like Herod, but who will ultimately turn the world upside down by means of his life and doctrine.

Like Samuel, Jesus will be left at the Temple. From a tender age, his words will astound the wise, and he will grow in favour with God and man. Yet, as time goes on, Jesus’ words will become more contentious (4.22–30). Although they will convert the hearts of some in Israel, they will harden the hearts of others (most notably Jerusalem’s authorities), until, in the end, they spell out the Temple’s judgment. ‘Not one stone will be left on top of another! Jerusalem will fall, the heavens will be shaken, and the Son of Man will come in power and great glory!’ (Luke 21). Like a depth charge, Jesus’ initial arrival in Israel will seem inconsequential, yet it will ultimately bring Jerusalem to its knees.

Luke: Poverty rather than riches

Equally important to note is Luke’s association of Jesus with the poor. While Matthew has Joseph reside in a house, Luke has him lodge in a guestroom. While Matthew has Jesus visited by wise men, Luke has him visited by (mere) shepherds. And, while Matthew has Jesus given gold and precious spices, Luke has him taken to the Temple along with a poor man’s sacrifice (cp. Lev. 12.8).

These details are significant. As far as Luke is concerned, the Gospel is fundamentally for the poor and downtrodden (3.5–6, 4.18, 7.22, 14.11, etc.). Jesus has come to inaugurate a Jubilee—a ‘year of favour’, a time when those who have lost their inheritance are given new hope (4.18–19)—, which is precisely why Luke mentions Caesar’s Jubilee-like decree, with each Israelite returned to his hometown.

Luke’s rationale

As we’ve noted, many commentators are unsatisfied with Luke’s narrative. They expect it to show a greater awareness of the events described in Matthew’s. Suppose, then, we try to include the flight to Egypt in Luke’s narrative (just as we previously tried to include the census in Matthew’s). As it stands, the text of Luke 2.39 reads as follows: ‘When Mary and Joseph had done what was required by the Law of the Lord, they returned to Galilee, to Nazareth’. Suppose we try to incorporate the flight to Egypt in this way:

When Mary and Joseph had done what was required by the Law of the Lord, they went to Egypt for a number of years and later returned to Galilee, to Nazareth…

Luke’s narrative now shows an awareness of its counterpart in Matthew. By the same token, however, it’s a less lucid composition. It also makes us wonder why Mary and Joseph went to Egypt, which (by Brown et al.’s logic) requires Luke to tell us about the massacre in Bethlehem (as well as the wise men’s visit, since the massacre otherwise makes little sense). Yet, as we’ve seen, Luke’s intention isn’t to introduce Jesus as a Moses-like deliverer born into royalty, but as a humble Samuel-like servant, who grows up in obscurity. Consequently, Luke isn’t interested in Herod’s activities. Luke is interested in the lower profile aspects of Jesus’ infancy—in the nearby shepherds rather than the shepherd-king of Micah 5.2, in the Temple rather than the palace, and in Nazareth rather than Bethlehem.

Final reflections

Matthew and Luke’s decisions about what not to include in their birth narratives are often seen as a point against their credibility. (If Matthew knew about Luke’s census, he’d have mentioned it; and if Luke knew about Matthew’s massacre, he’d have mentioned it; and so on.) As we’ve seen, however, Matthew and Luke’s decisions can’t be assessed so simplistically. Matthew and Luke don’t always tell us everything they know, and their omissions serve a purpose.

For Matthew, Jesus is a new Moses, who goes toe to toe with the world’s Pharaoh-like Herods, while, for Luke, Jesus is a more subversive and Samuel-like figure—a man whose ministry lifts up the poor and downtrodden and brings down a corrupt regime. Consequently, Matthew has good reason to mention Herod, the wise men, and the flight to Egypt and not to mention the decree, the shepherds, and Jesus’ visits to the Temple, while Luke has good reason to do the opposite. Contra Brown et al., then, Matthew may have known about Caesar’s decree (etc.) and yet not mentioned it, while Luke may have known about Herod’s massacre (etc.) and yet not mentioned it.

Where, then, do our considerations leave us? If we want to engage with Matthew and Luke in a fruitful way, we need to engage with them on their own terms rather than on the basis of what we think they would (or should) have said (had they known about it). Matthew and Luke describe different aspects of Jesus’ birth since they portray Jesus as the culmination of different strands of biblical history, and a careful consideration of their narratives enables us to appreciate both the sophistication with which they do so as well as the remarkable character of the Saviour they describe.

James Bejon is a junior researcher at Tyndale House—an international evangelical research community based in Cambridge (UK), focused on biblical languages, biblical manuscripts, and the ancient world.

James Bejon is a junior researcher at Tyndale House—an international evangelical research community based in Cambridge (UK), focused on biblical languages, biblical manuscripts, and the ancient world.

It’s amazing how often arguments from silence are used in the study of Christian origins. Just about any report in the Gospels can be discounted if there is a lack of external corroboration. In reality, arguments from silence are usually worthless. Those who use the argument should try collecting a year’s worth of daily newspapers. They can then compare this with the sum total of our knowledge about Judaea in 4 BC.

It was only 2-3 weeks ago that someone commented re the resurrection of Matt 27:52 that it was unlikely to have happened, since otherwise the other gospel writers would have referred to it. It’s good to have the facile reasoning challenged.

Right, Steven. We really need to get in the habit of challenging arguments from silence. Sometimes we can speculate as to why a particular author would not have mentioned something but there is no obligation to explain it. In general, silence cannot be used to overturn positive evidence. So what about the resurrection of the saints in Matthew?

There is a sceptical argument against the resurrection of Jesus that goes like this. Mark wrote first and he ends the story with the discovery of the empty tomb. This is supposedly the first step in the creation of the “legend”. Matthew, Luke and John then expand the legend. One problem: it was obviously well established that the Risen Jesus had appeared to many people before the Gospels were written – as 1 Corinthians shows.

But this faulty line of “reasoning” all springs from an attempt to exploit an argument from silence – in particular, the absence of any appearances in Mark. We don’t why Mark chose not to record any appearances but it certainly doesn’t show that no one had ever heard about the appearances before the other Gospels were written. What it does show is that an author could omit a very important part of the story even though it was well known. And if the appearances of Jesus could be omitted then other aspects of the story could be omitted.

Actually I think a number of scholars are of the opinion that Mark probably did write a longer ending but that it was lost. So it may be it was not his choice! Alternatively apparently there is precedence of such an abrupt ending of a writing in ancient works, though I’m not sure how convincing that is. But in the end we simply don’t know.

Peter

I think N.T. Wright is of that opinion. I think the majority reject that view and I’m inclined to agree, although it does seem curious that Mark would have ended his account so abruptly. Either way the sceptical argument fails.

Thank you.

I tend to think of Luke portraying the birth of Jesus into a Roman world, which is the world of his readers, while Matthew focuses on the more Jewish elements, for what we may presume is his intended primary audience.

It is helpful to be reminded of the different OT roots in each gospel’s account.

I am not sure that the jury would be convinced by these arguments – a Scottish court might return Not Proven.

The question of dating the birth of Jesus is not addressed in this article, nor the thorny issue of the census, but the more subtle question is asked quietly about the primacy of a theological interpretation, or a factual basis when we come to read the gospels. How much do we allow the gospel writers to organise their material, choose wording, frame events, combine teaching etc before we have to acknowledge that these are texts which no longer fit within our concept of fact (eg genealogies). It does not mean they are fiction but it makes us ask questions about the lens of the writer, the lenses that we have assumed, and the partiality of the texts. It makes interpretation a deeper task and a more adult task and a humbler task where we search for a greater clarity with vigour, while acknowledging that there is richness, otherness and even a problematic in the texts which may push back against our desire for clarity.

When we are too focused on the right interpretation we may be overly defensive to those who question the implicit bias or focus of a writer (for focus implies other things are not in focus), their centrism whatever that might be, but which marginalises other voices to some or greater extent. An obvious example being to what extent Luke enables and or limits the voices of women, or the significance of the Gentile others in Matt 1-2 and how we should interpret that now.

It is a conversation that continues ..

What a great article. Thank you muchly for demonstrating the intertextual big picture themes and patterns in scripture which does not render them any less historical, factual.

It is fascinating that those of the higher historical critical school may see redactors everywhere, they may be unable to see the editorial abstracts of the Gospel writers, along whole canon longitudinal lines, and purposes and fulfilment, of in effect scripture interpreting scripture.

Peter Reiss, I’d be interested to know how your today’s understand of *fact* differs from the past. There is a correspondence : correspondence to *is*.

Further, the burden to proof is yours, in opposition to the differing witness of the Gospels. Incomplete does not equal incorrect or inconsistent. Omissions do not equal error.

There is also a risk in any biblical scholarship that authorial intent is omitted, in the canons of construction not only the human writers, the Gospel writers, but the ultimate author and compiler, editor God himself.

I guess one question is in what way we treat the genealogies as *factual*, whether in the names that they give and / or the generations they omit. How do we read the two very different genealogies, from Matthew and from Luke or explain why one chose to give a very different genealogy from the other? Within the understanding of writing *then* they may well be acceptable, but a modern reading might well claim they are not to be treated as factual in the way we understand factual.

The explicit use of OT texts to support or even justify what happened is clearly theologising (Matthew) and Luke seems to do it more implicitly, as is the grouping of teaching, the framing of parables etc, something Ian often helpfully points out in his studies, but something that points to a theological purpose shaping the way the text is set (out).

Quite possibly also the census – at the time when Augustus declares the Pax Romana and Jerusalem is under direct rule from Rome – Luke subversively says the Prince of Peace is born. but it is not AD6 when Jesus is born.

And when we tread timorously into the realm of the author’s intention, let alone God’s inspirational involvement, then we are moving further into the interpretational jungle – and the danger is that we interpret how we want it interpreted, even where texts do not readily lead to such an interpretation.

Very interesting, I think it’s a good overview and argument.

Who is Joash’s gentile guard, though?

Hi Kyle. Thanks for the question. I should have been clearer. When Joash is crowned king, he’s assigned ‘the Carites’ as guards (2 Kgs. 11.4), who are generally thought to be Gentiles (related to the Carians). They also seem to be referred to as ‘Cherethites’ in some passages/traditions. James.

Thank you, James.

An excellent article, James. You’re comments on why Matthew and Luke highlight or omit different aspects is undoubtedly correct. But I wondered given the differences, do you accept both as equally ‘historical’?

I also wondered if your research has shed any light on the whole question of who wrote their gospel first, and who was aware of what? I know some think rather than some ‘mythical’ document Q, Luke may have been aware of and used Matthew’s Gospel. Any thoughts?

Peter

Hi Peter.

Yes, I do personally accept both as equally historical. Whenever you write history, you have to decide what to include and what to exclude. A helpful example is Stephen’s speech in Acts 7. Stephen could have spoken about any number of things that occurred over the c. 2,000 years since Abraham’s call. He focuses, however, on incidents where God’s Messiahs are rejected by Israel and instead accepted/helped by Gentiles (Joseph, Moses, David) because he wants to present Jesus as their culmination. As a result, Stephen fails to mention all sorts of significant historical figures (Joshua, Gideon, Solomon, etc.). That doesn’t, however, make his account any more or less historical than an account with a different focal point (or even a more exhaustive account). And I’d say the same thing about Matthew and Luke’s. They focus on the aspects of history they want to focus on.

Re who wrote what first, I genuinely have no idea. Ultimately, what we’re trying to do when we answer such questions is look back on the compositions of three people about whom we know very little 2,000 years after they written and decide how they came to be. And I think such questions are beyond us.

Thanks for the interest,

James.

So James,

Are we privacy to any of Jesus Emmaus Road Seminar?

We surely are? Notwithstanding a lot of scholarship, or perhaps because of longitudinal biblical scholarship.

Correction: for privacy read privy.

I seem to remember reading that scroll length itself imposed a constraint. Is that right? Luke’s is the longest gospel, perhaps reaching the maximum length, with Matthew’s close behind. John says at the end of his that he had to be very selective, and it is commonly thought that he decided to speak up, long after the others, in order to fill significant gaps and provide a different perspective. If scroll length was a constraint, it inevitably followed that choosing what to include entailed choosing also what not to include. While many teachings and incidents bore repetition, there was no point in simply repeating entirely what gospel writers had already written.

Yes it was a constraint as was the significant cost of papyrus, which is why the typical follower was unlikely to be able to afford copies hence the importance of reading them in churches.

It may very well be the constraint of the length of the papyrus scroll that meant Luke had to use 2 volumes for his gospel and Acts. But I’m not sure that explains the rather short and abrupt ending of Mark.

Peter

Hi Kyle. Thanks for the question. I should have been clearer. When Joash is crowned king, he’s assigned ‘the Carites’ as guards (2 Kgs. 11.4), who are generally thought to be Gentiles (related to the Carians). They also seem to be referred to as ‘Cherethites’ in some passages/traditions. James.

Good post. I learn something new and challenging on sites I stumble upon everyday. It will always be helpful to read content from other authors and use a little something from their web sites