The gospel lectionary reading for Lent 2 in Year B is Mark 8.31-38, Jesus’ call on all those who would follow him to ‘take up their cross’ and walk the path that he did. This includes one of the first verses I learnt by heart as a new Christian (Mark 8.34), but it is also the subject of much misunderstanding. On the one hand, the phrase ‘to take up one’s cross’ or ‘bear a cross’ has in common parlance been detached from the question of following Jesus and is now used to mean ‘carry any burden in life’. On the other hand, some traditions of Christian reading suggest that we are saved by suffering as in this Russian orthodox post:

Following Christ does not necessarily mean more happiness or less suffering. In Christ, any happiness and suffering we experience will find its fulfillment. We can share our joy with those around us, especially those who are suffering, in this way co-suffering with them. And when we suffer, we can let others co-suffer with us.

We should take comfort in the fact that Christ saved us by suffering for us. Suffering is salvific.

We need to look carefully at what Jesus is saying here, in the context of the narrative of this section and the whole gospel.

The opening of our passage ‘And he began to teach them…’ shows both how this passage is connected with what has gone before, but also how it marks a decisive change of direction. We have just had the climactic centrepiece of the gospel narrative, where, after many false starts and much misunderstanding, the disciples in the person of Peter have finally realised who Jesus is: ‘You are the Christ’. But this has come after the two feeding events, two lots of teaching, and the double healing of the blind man (‘I see men like trees walking’, Mark 8.24) shows that the disciples will need more help to understand the truth of the matter.

We saw in last week’s reading from Mark 1 that, from the beginning, there are mixed indications of Jesus’ exaltation and his humility. He is the beloved Son, but this sonship means obedience to the Spirit, and will ultimately lead to the obedience of a sacrificial death. But so far this has been a muted undertone of the narrative, and the main theme has been the dynamic power of Jesus’ ministry. But now, Jesus begins to teach them about his coming suffering and death, and this takes over as the major theme in the gospel symphony.

This change is marked by Jesus’ use of the term ‘Son of Man’ to refer to himself. The phrase occurs 13 times in the gospel, of which 11 occurrences are in the second half. In the Old Testament, the Hebrew phrase ben adam has three aspects to it. First, it simply means ‘humanity’ in its creaturely reality, in some ways small and insignificant, but exalted by being made in God’s image:

‘What is man that you are mindful of him, the son of man that you care for him?’ (Ps 8.4 ESV)

We need to note here that two occurrence of ‘man’ here actually mean ‘human being’, so that the TNIV translate these as ‘mere mortal’ and ‘human beings’ respectively. This is a much better rendering of the meaning (and the ESV’s use of ‘man’ here is unjustified as a translation), but when we loose the grammatical construction of ‘son of man’ then we miss the connections with other places where the phrase occurs.

Secondly, ‘son of man’ emphasises human fragility more specifically in contrast with the sovereignty and majesty of God in Ezekiel, where it is the way the God addresses the priestly prophet. After his terrifying apocalyptic vision of God exalted on his ‘throne chariot’ (later known as his merkavah) Ezekiel hears God addressing him:

Such was the appearance of the likeness of the glory of the LORD. And when I saw it, I fell on my face, and I heard the voice of one speaking. And he said to me, “Son of man, stand on your feet, and I will speak with you.” And as he spoke to me, the Spirit entered into me and set me on my feet, and I heard him speaking to me. (Ezek 1.28–2.2)

Again, some modern translations render the phrase as ‘Mortal man’.

Thirdly, the ‘son of man’ is the human figure in Daniel’s night vision, representing the fragile people of Israel as they are threatened by the beastly empires emerging from the sea of the nations, exalted to the throne of God and giving an everlasting kingdom; note that the ‘coming of the son of man’ is a ‘coming’ from the earth to the heavenly throne, and not the other way around.

I saw in the night visions, and behold, with the clouds of heaven there came one like a son of man, and he came to the Ancient of Days and was presented before him. And to him was given dominion and glory and a kingdom, that all peoples, nations, and languages should serve him; his dominion is an everlasting dominion, which shall not pass away, and his kingdom one that shall not be destroyed. (Dan 7.13–14)

Jesus’ use of ‘Son of Man’ as a description of himself in Mark (note that this term is never used by others of Jesus) reflects these different emphases, and can be grouped in three or four kinds (the last two groups could be seen as variations on a single theme).

- Jesus’ present authority, perhaps as the archetypal human created in the image of God (Mark 2.10, 2.28)

- Jesus’ rejection and suffering, as the archetypal mortal, fragile human (three predictions in Mark 8.31, 9.31, 10.33; other sayings about his suffering and rejection in Mark 9.12, 10.45, 14.21, 14.41)

- His exaltation to the throne of God, the ‘coming [erchomenos] of the Son of Man’ from Dan 7.13 (Mark 13.26, 14.62)

- His vindication, first in being raised from the dead, and then his returning glory to judge (Mark 8.38, 9.9).

Thus it is that the title of ‘Son of Man’ captures the paradox of Jesus’ authority and his humiliation that we find in the narrative juxtaposition of the revelation of his identity as God’s anointed one to the disciples, his declaration that he will suffer, die, and rise again, and the Transfiguration revealing his glory as the deathless one who stands in God’s presence.

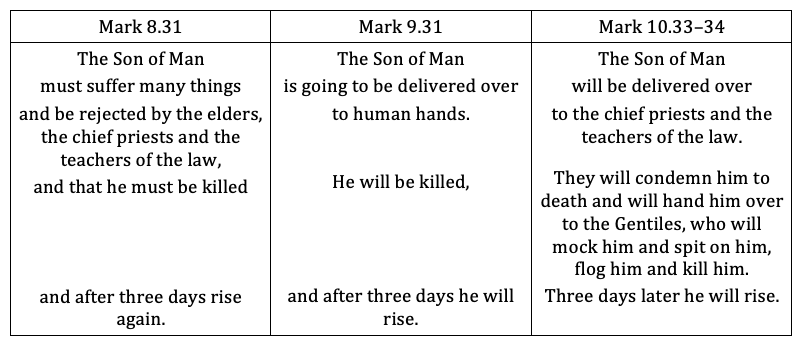

This is the first of Jesus’ three predictions of his passions. We can see by comparing them that his opponents are described in most detail here, but that what matters is that these are ‘human hands’ (prediction 2) and that the Gentiles (that is, the Romans) will have the key role in his suffering and death (prediction 3).

The fact that he says all this ‘plainly’ is another contrast with his teaching in the first part of the gospel, where he ‘said nothing to them without using a parable’ (Mark 4.34).

The exchange with Peter is stark, almost brutal, in its directness. Peter takes Jesus aside, in order to correct him privately; after all, it is Peter who has had the revelation of who Jesus really is, so perhaps he feels he has superior insight, and this teaching about his suffering is a new direction from Jesus, so it is no wonder that Peter is alarmed by it.

But Jesus reciprocates; where Peter has rebuked Jesus in private, Jesus rebukes Peter in front of the other disciples (though not in front of the crowd). This is such an important correction that it needs to be heard by the others lest they are harbouring similar thoughts which they have not articulated. The labelling of Peter as ‘Satan’ (though not as ‘The Satan‘) is rather shocking—but it shows that merely human understandings can function as dangerous obstacles to the plans of God. Does the sharpness of Jesus’ rebuke give us an indication that he himself was struggling with the reality of God’s call on his life and ministry?

As with other well-known sayings, we live with the legacy of the Authorised Version here: ‘Get thee behind me, Satan!’ The danger is that we think this simply means ‘Get out of my way!’ In fact, Jesus is here using the language (opiso mou, ‘after me’) of discipleship, and he picks up the identical phrase in the following saying to the crowds, ‘If anyone would come after me…’

It is striking that Jesus now calls the crowd to him, ‘with his disciples’. He is now teaching both groups together in the same way, and making the conditions of discipleship, of following him, plain for all to see—the public/private distinction in his teaching is left behind.

And Jesus sets three conditions for becoming a disciple—or, rather, three aspects of what being a disciple of his involves, the first two of which are easily misunderstood. The first is to ‘deny oneself’; the sense here is not about self-loathing, but of disregarding the kinds of claims that we normally make for ourselves. Louw and Nida’s semantic lexicon suggests that the term aparneomai has the sense:

‘to refuse to pay attention to what one’s own desires are saying’ or ‘to refuse to think about what one just wants for oneself.’ In certain instances other kinds of idioms may be employed, for example, ‘to put oneself at the end of the line’ or even ‘to say to one’s heart, Keep quiet.’

This is precisely the attitude that we have seen in Jesus’ ministry, focussed on obedience to the Spirit and meeting the needs of the people, in the first half of the gospel.

The second is to ‘take up one’s cross’. In the context of the first century, this could only have one meaning: someone who was carrying a cross was on his or her way to a shameful execution as a slave or a criminal. There is no sense in which this is a ‘burden’ to be carried through life; it is a burden only carried on the way to death.

James McGrath is not untypical of scholars who are sceptical about this saying originating with Jesus.

Taking up one’s cross certainly does not seem to have been an already-existing expression, nor is such a saying likely to have existed in that period. It seems as though it was only the reality of a crucifixion that could inspire such an idiom as in the case of Jesus and early Christianity. No one is likely to have used this horrific form of execution as a metaphor, just as we do not find “beheaded,” “put in the electric chair,” or “given a lethal injection” used metaphorically.

Of course, it is not inconceivable that a figure who thought of himself as the Messiah – whether one who would face rejection or one who would soon be victorious – could have called his followers to be prepared if necessary to face execution by the Romans. But possibility is not enough, and a historian will have to conclude that this saying is more likely to be a post-crucifixion invention than an authentic saying of the historical Jesus.

But it is worth noting here that if unlikely things never actually happened, 90% of history would disappear. McGrath is sharing the assumption that Jesus could not do novel or unusual things; and the fact that this saying, as Jesus expresses it, appears to leave no traces in the other writings in the New Testament is a strong argument against it being a creation of the early Christian community. What McGrath does help us with is to see what a shocking metaphor this is—though in context it is not only an image of death, but one of a particularly humiliating and shameful death.

And of course, both Jesus and his hearers would be perfectly familiar with this idea, since it was a common form of Roman execution. As is characteristic of Jesus’ use of vivid metaphors, he then goes on to expound the consequences in the three-fold saying about ‘saving’ and ‘losing’ one’s life. Once again, traditions of translation push these sayings slightly out of shape; the term psyche (from which we get ‘psychology’) is translated ‘life’ in the first saying, and ‘soul’ in the pair of second and third sayings. The term does not mean ‘soul’ as defined against ‘body’ and ‘spirit’ in a trichotomous (three part) description of human life, but simply ‘life’ in the sense of the inner reality of who we are. The implication is that following Jesus, denying one’s own desires and agenda, and being prepared to experience discomfort and shame as part of that journey, is the only way to true life and salvation. It is not that our suffering is salvific in any direct sense—but that what we need to do in being ready to following Jesus will likely lead to hardship, as we share the life that he lived.

The final saying, in Mark 8.38, might appear to change the emphasis and direction somewhat. But in fact it picks up two issues already implicitly present in the earlier saying. The first concerns ‘shame’, and reminds us what a shameful thing it was to be crucified. The second locates the question of discipleship in eschatological context, not least by invoking the eschatological significance of Jesus’ identity as ‘Son of Man’. The reason why following this Son of Man will involve hardship, suffering and public shame is because Jesus is the one who inaugurates the age to come, the promised ‘kingdom of God’, and those who belong to this, passing, age oppose and reject him. This eschatological divide is made more explicit in the Fourth Gospel (see the love/hate language in relation to the world in, for example, John 7.7), but it is a feature of every part of the New Testament, and is the reason why the primary quality of being a disciple of Jesus, both then and now, is ‘patient endurance‘.

This message is found elsewhere in the gospels and letters: ‘if we have suffered with him we will be raised with him’ (2 Tim 2.12). And it is a message of discipleship that continues to echo down the ages: ‘When Christ calls a man, he bids him come and die’ (The Cost of Discipleship).

Jesus gives 3 plenary homilies after his 3 passion predictions are misunderstood, and as the scolding of James and John involves reference not only to their own deaths but also to their participation in the manner of Jesus’s own death, it is probable that this present passage refers to Peter’s own death by crucifixion, the same manner whereby Jesus suffered death.

Are you saying that Jesus said these words with, as it were, a knowing glint in his eye with regards to Peter?

I do think the structure demands it.

One of the best personal illustrations of cross-centred discipleship is a short extract towards the end of Galatians. Paul declaims —” Let no one cause me trouble – for I bear on my body the marks (stigmata) of Jesus. It is highly improbable that Paul had in mind any inclination towards self-flagellation. It is that extremely likely he was referring to the beating, torture and imprisonments he endured during his ministry.

Yet the astonishing thing is that he does not relate them to his past (and present) experiences. No! Paul here was relating his suffering to his union with Christ; first as a slave of Christ( at that time, the “mark” was the branding of a slave) but secondly by sharing with Christ in his death (Romans 6 – union with Christ) and finally therefore in his resurrection (“what counts is a new creation” [6:15]) . Suffering gives way to victory!

In the light of this, surely we must support more wholeheartedly and passionately our persecuted brothers and sisters throughout the world. It is they who truly bear the marks. But it is they who are wearing the crowns!

Indeed. From what I can see, few Christians in the West (perhaps particularly clergy who seem to spend their whole time in the company of other believers) suffer genuine persecution or shame. If it is inevitable, what does that say about our salvation given Ian Paul’s words above?

I would still tend to think that carrying one’s cross is linked to burdens, though not solely. Could it not be seen as part of putting to death that part of ourselves that fights against God’s will? I dont think the suffering can be simply limited to that caused by external forces.

Also even if the Greek translated ‘get behind me , satan’ could mean more of in a disciple sense, does not the context warrant the ‘traditional’ understanding, as Peter has just started to rebuke Jesus for saying he was going to suffer and be killed, that he was trying to dissuade him from such thoughts, thus getting in the way of God’s plan?

Peter

The argument that the phrase ‘Son of Man’ is intended to evoke Dan 7 has always seemed to me somewhat circular. The Hebrew phrase is common (e.g. Dan 8:17) and just means a son of Adam, i.e. a human being. ‘Adam’ seems to me the strictly correct translation, since logically one can only be the son of an individual, not of a collective noun. However bleached, Adam retains its original meaning as the individual progenitor of all mankind, in the same way as the ‘sons of Israel’ retains the literal meaning, i.e. sons (-> descendants) of the man Israel, at the same time as being bleached down to ‘Israelite people’.

The phrase in Dan 7:13 must bear its normal meaning if it is to mean anything: Daniel saw somone who looked like a human being and yet was more than a just a human being – as also Dan 10:16, and conversely Dan 3:25 (‘son of the gods’ or even ‘son of God’). In styling himself ‘Son of Man’ Jesus was indicating his dual ancestry: he was both a son of Adam and a son of God (Luke 3:38). Before the NT, ‘Son of Man’ was not a messianic title and in the NT therefore cannot have any reference to Dan 7:13.

In Deut 32:8, poetic parallelism makes the antithesis fairly explicit: ‘sons of God’ balances ‘sons of Adam’.

Hebrew has a second word for ‘man’, enosh, so I would be interested to know why you think the ESV is inadequate at Ps 8:4, where enosh (man in either an individual or collective sense) seems synonymously parallel to ben adam.

It isnt so much the phrase ‘son of man’ on its own, but rather the very similar language that Jesus uses concerning himself as the son of man compared to that used in Daniel.

Compare, for example, what Jesus says in John 5:27, Matt 24:30 & Mark 13:24-27 with Daniel 7:13-14.

Peter

Yes, one can see the relation between the passages cited, indicating that Jesus will fulfil the prophecy, but it does not follow that the title ‘the Son of Man’ itself evokes Daniel. It clearly doesn’t, because the figure in Dan 7:13 is only like a son of man, whereas Jesus is the son of man. The expression indicates an archetypal role which he uniquely fulfils. ‘The Son of Man’ has no analogue in the OT, with the partial exception of Seth, the appointed one. Just as ‘son of man [collective noun]’ makes no sense in Hebrew, it makes no sense in Greek (huios tou anthropou] either (or English). It makes sense only if one recognises that it is a Hebraism going back to ‘son of Adam’ or ‘son of the man [referring to Adam]’.

One could also fruitfully compare I Cor 15:45 – Jesus as the last Adam – and Eph 2:15, 4:24 and Col 3:10, where Jesus is the ‘new man’ (anthropos in the Greek, not ‘self’).

You continue to emphasize the words ‘son of man’ rather than the context in which they are referenced, in Daniel and the words of Jesus about himself. The picture being painted is clearly the same as Daniel.

Think about it. What would jewish hearers of Jesus’ words be thinking? Probably, that seems familiar, where have I heard that before? Then those who know their Scriptures realise it comes from Daniel – son of man, coming on clouds of heaven, glory, kingdom, power, authority…the implication is clear.

The short conversation between the Jewish High Priest and Jesus is also interesting: ‘The high priest said to him, ‘I charge you under oath by the living God: Tell us if you are the Christ, the Son of God.’ ‘Yes, it is as you say,’ Jesus replied. ‘But I say to all of you: In the future you will see the Son of Man sitting at the right hand of the Mighty One and coming on the clouds of heaven.’ ‘

So the Jewish authorities at the time link the Messiah to the Son of God, which Jesus confirms refers to him, but then also links the Son of Man, ‘coming on the clouds of heaven’ yet again evoking Daniel.

So Messiah = Son of God = Son of Man = Jesus.

You would have to have a specific bias, for example, a refusal to accept the Divinity of Jesus, ie a heavenly being per Daniel, to not see this.

What ‘picture’ are you referring to? This conversation starts from Mark 8:31. How does that evoke Dan 7:13? How does the first occurrence of the title, in Mark 2:10? You pretend to understand what ‘son of Man’ means but you don’t indicate what. How can anyone be a son of the whole human race? You don’t say.

I have said it before: the figure in Dan 7:13 is only like a son of man. That phrase depends on prior understanding of what a ben Adam is, a phrase which occurs 187 times outside Daniel, often synonymously parallel with enosh, meaning ‘man’ or ‘a man’ (e.g. Ps 8:4). If listeners thought “that seems familiar, where have I heard that before?”, those 187 occurrences plus the two in Daniel provided the answer. By your logic Jesus should have called himself “the One like a Son of Man”. By your ‘Messiah = Son of God = Son of Man’ logic, Ezekiel (Ezek 2:1) was the Messiah.

Correction: for ‘189’ read ‘107, and for ‘187’ read ‘105’, most of the occurrences being in Ezekiel.

… Also John 19:5: ‘the man’, as in Gen 1:27, 2:7 etc.

I couldnt respond to your further response above so im replying here.

You continue to refuse to admit the clear similarity in language that Jesus uses when referring to the Son of Man, ie himself and the picture portrayed , with that in Daniel. It couldnt be more obvious.

Just notice how, in the picture, ALL of the others are out of step with Jesus. Did the artist intend that? And what is the reason? (Maybe, the fact that we are unable to measure up?

Would you see a parallel of some sort or at least some sort of allusion to the OT concepts of sacrificial offerings ? When you gave a sacrifice it became holy and was no longer yours to do with as you wish, it is beyond your control and you have no say over how it is used. In the same way when you take up your cross you become holy, that is taken out of normal use and dedicated to God service, so your life is no longer yours to do with as you please but you have give it over to the Lord for him to use as he see fit in this service ? obviously our sinful natures kick in and there is the constant struggle, or there should be, between doing what we are called to do and doing what we want to do.