Mark Broadway writes: Does suffering matter? This is a question that many will have tried to answer, scouring philosophy textbooks from the safety of the library. Perhaps more importantly, in times of distress and pain, a more poignant question arises from the depths of a heart: does my suffering matter? As a society, we can count the number of those who suffer, but can we account for suffering?

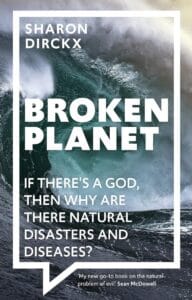

Broken Planet (Sharon Dirckx, IVP 2023) fruitfully engages with a particular category of suffering—that which arises from natural disasters.

Prior to the turmoil of 2020, many of us doing pastoral ministry in the UK had only a second-hand experience of care for those caught up in natural disasters. No doubt our prayer teams interceded for those abroad who were enduring the latest hurricane, typhoon, or earthquake. Hopefully our churches were at the forefront of fundraising for global relief efforts. But, by and large, hurricanes, typhoons, and earthquakes are not the sort of things that directly impact on those in the South Wales Valleys where I live. True enough, I have had the odd parishioner, here and there, with relatives abroad. At times these people were subject to forces of nature well beyond what we might expect to endure in the UK.

It has been rare. And yet two important factors spring to mind. First, recent deterioration of weather conditions in the UK leading to severe storms and flooding. Secondly, the effect of globalisation, meaning that we are becoming ever more global in our outlook. Mass media has, for decades, been beaming news of catastrophes from around the world into our living rooms. As a result, we probably know more about the Boxing Day Tsunami of 2004 (even though it happened on the other side of the world), than an historical incident such as the Lisbon earthquake of 1755 (despite it happening much closer to home and having a major impact on Western thinking about these questions). Dirckx helpfully looks at both of these events, and many others. Social media has taken us a step further, as we can now hear directly from, and even engage with, those in the midst of crises in real time as situations develop.

The Global becomes Local

Global suffering is nearer than ever before. The Covid pandemic—rapidly becoming an historical event as we approach a half decade since the first lockdowns—meant that for the first time, global suffering was now also local suffering. Old points of debate around the goodness of creation, the moral implications of suffering, and role that God plays in all of this mess were being asked with new gusto. Crucially, they are also being asked in a context which has changed. No longer are these questions framed in a fairly straightforward battle between theist and atheist. Instead, we see a much more complex postmodern milieu, where public intellectuals like Richard Dawkins or Christopher Hitchens have been replaced by people like Jordan Peterson or Tom Holland. Here the language of faith and religion is given new life—but often confusingly, and with new implications.

Questions are less and less focused on whether God exists, and more and more time is being given to questions of meaning. If Christians can find meaning in suffering, they have a vital part to play in public discourse, and this book can help us take that step. As Parliament now discusses assisted dying, with new legislation likely to come into force, understanding suffering is vital for Christians. This is true not only for those Christians who work in pastoral ministry, but for all of us who want to be able to articulate why the Gospel remains ‘good news’ in the midst of all the bad news that fills our newspapers and social media feeds.

It is into this context that Sharon Dirckx writes. Her work provides a useful set of charts to navigate these waters—and Dirckx is well placed to guide us. With an academic record and research history that has spanned both brain imaging and theology, she expertly relays to us the questions that are asked of God, and how we might begin to understand our role in replying.

The book is structured around ten questions, each of which forms the springboard into a discussion of the science behind natural disasters, the philosophical concepts we utilise to understand and communicate what’s happening, and the theological principals that can help us to tie it all together. These questions range from the impossibly broad “If God is real, why are there natural disasters?” to the relatable “What should my response be to a natural disaster?” At 200 pages long, we aren’t looking for an exhaustive answer to each question raised—this is not Dirckx’ Summa Theologica as she herself makes clear. This is, however, an insightful introduction to some of the perennial questions that, far from diminishing our faith in God, lead us to a greater trust in his saving purposes in Jesus.

What’s Key? Testimonies of Survivors and Aid Workers.

Apologetics, or giving a reasoned defence of the faith that we hold (1 Peter 3.15), obviously plays a significant part in this work. Dirckx is, after all, an adjunct lecturer at the Oxford Centre for Christian Apologetics, and author of Why? (IVP 2021), which looks more broadly at concepts such as good and evil. She is a regular on radio and podcasts, bringing a sharp scientific mind and robustly Christian outlook to a range of topics. We would be disappointed if she were not to offer us some apologetics. She certainly does, and we will come to explore this shortly, but ‘reasoned defence’ is not the key aspect of this work. Rather, Dirckx builds her case around the testimonies of real people who have lived through various natural disasters. She puts real people with real experiences of suffering front and centre, allowing their voices to be heard. Each of her own chapters are punctuated with extended narratives from others, stories compiled from her research in producing this work.

These dozen narratives add a distinctive flavour to the whole work, as Dirckx demonstrates that to explain suffering is not to explain it away. Quite the opposite, says Dirckx, as she outlines the deeper question of ‘does my suffering matter?’. Reading this book is not to help us dismiss the cries of those in pain, but to help us to understand the factors that lead to human suffering, and the imperative to uphold human dignity to the glory of God. This leads us to the conclusion of her opening chapter, where the thrust of the rest of the book is presented. Here she suggests that suffering, and the moral challenge that it raises, are both questions that find their ultimate solution and their best articulation in a life lived in relationship with God through Jesus.

The return, again and again, to lived experience through the anecdotes and narrative of those who have first-hand testimony of faith in the face of disaster prevents this book from becoming an exercise in theory. This is not to say that Dirckx allows it to descend into an appeal to emotion either. She wants to demonstrate that faith in God is not only a reasonable solution to the question of suffering, but that it is in fact the best way to begin to explore our concern for the human experience of suffering in the first place.

Theodicy and Me

In order to root our discussion of suffering, and care for those who experience it, in the fruitful soil of faith, Dirckx needs her readers to grow in understanding of some theological and philosophical concepts. She will introduce us to a number of ideas throughout the book—ideas or phrases such as ‘theodicy’, ‘the best of all possible worlds’, the ‘is/ought fallacy’. Moreover, she will help us to use the teaching of Jesus as an interpretive tool for assessing God’s agency in the world. All of this is helpful stuff. Dirckx does not assume her readership to be comprised exclusively of theologians, and so takes her time to give an overview of many of these concepts. It is only an overview, and so some will want to scour the notes section at the back for further reading. For those who are theologians, a lot of this will not be new. But the powerful way in which these ideas are interwoven with narrative gives them fresh resonance.

Excitingly for me, Dirckx goes well beyond merely outlining the claims of classical theism. She does not simply appeal to ‘God’, but is keen to introduce us to the person of Jesus Christ—his atoning death, resurrection, ascension, and promised return. Although the Gospel of Jesus runs like a thread through the whole work, the later chapters build in evangelistic energy. So much so that the concluding paragraphs are really an evangelistic appeal building on two chapters that help to outline much evangelical Christian teaching on the atonement and substitution, as Dirckx makes abundantly clear:

Jesus hasn’t just suffered like us, but also for us. We are told that somehow his death benefits us, and that somehow ‘by his wounds we are healed’.

This is a timely reminder for all of us, but especially for those on the fringes of church, who may have been stirred to ask big questions by their own suffering, or by reports of natural disasters, that this could be the word in season they need to enable them to put their trust in Jesus.

This is a timely reminder for all of us, but especially for those on the fringes of church, who may have been stirred to ask big questions by their own suffering, or by reports of natural disasters, that this could be the word in season they need to enable them to put their trust in Jesus.

I began this book review by asking whether suffering, especially actual personal suffering, matters. The answer is that it does. Our suffering matters to God, who has experienced suffering in the person of his Son. That suffering was not in vain, but was instrumental in the redemption of the world. Our suffering, although different, can be understood in the light of the divine image that we all bear, and the suffering of Christ to redeem us. There are many questions left to explore, but in Broken Planet, Sharon Dirckx takes us a long way towards asking and answering them.

Mark Broadway is Ministry Area Leader in the Ministry Area of Penybont ar Ogwr in South Wales. He is Honorary Assistant Chaplain in the Princess of Wales Hospital, and is an operational member of the crew at RNLI Porthcawl. His book, Journeying with God in the Wilderness, is available now from IVP.

Mark Broadway is Ministry Area Leader in the Ministry Area of Penybont ar Ogwr in South Wales. He is Honorary Assistant Chaplain in the Princess of Wales Hospital, and is an operational member of the crew at RNLI Porthcawl. His book, Journeying with God in the Wilderness, is available now from IVP.

Buy me a Coffee

Buy me a Coffee

I have not read this book by Sharon Dirckx, but I have heard her speak on the subject and noted that she never once mentioned Satan. She is a philosopher not a biblical theologian and this article follows that path (with just one Bible reference). It is a path that Augustine laid the foundations for with his ‘blueprint’ concept of providence.

I would argue Satan and the fallen angels have agency and volition (it is the risen Christ that refers to ‘the power of Satan’, Act 26:18) — and are the source of all evil and suffering — directly, or via human agency, unless Scripture specifically says so.

Of course, this is not to deny that God is the author of all first causes — but that is not the world we live in. If a mother’s child is knocked down by a car through no fault of their own — it is the car driver that killed the child not the mother — even though that child would not have died if she had not given birth to them.

I believe it is C.S. Lewis who pointed out that if humans were denied volition and agency the world would be a meaningless place to live, and I suspect the same applies to the unseen realm — for some reason God does not want to deny them volition and agency until the eschaton.

In Protestant orthodoxy we have managed to get ourselves in a lamentable place over this, demonstrated by the fact that one of our most foremost theologians when asked to write a book on the COVID pandemic, made this bald statement:

“Alongside this Israel-and-God story there runs the deeper story of the good creation and the dark power that from the start has tried to destroy God’s handiwork. I do not claim to understand that dark power.”

– and he simply moved on.

N. T. Wright, God and the Pandemic. London: SPCK, 2020, 14.

By our own response we made Covid a lot worse than the bad flu epidemic to which it was equivalent in mortality. Nor am I convinced that it was a *natural* disaster.

There’s an interesting question around a lot of this; two things to note – can we really distinguish so sharply between human agency and natural causes as though humans are not at all part of nature? And, this thread is picked up in the book, not only with covid, but with all sorts of thing, human action and inaction often makes things worse

The distinction is pretty clear if it was manufactured by GM in the Wuhan Institute of Virology – as I am willing to advocate.

questions range from the impossibly broad “If God is real, why are there natural disasters?”

That is not impossibly broad, and the Bible wouldn’t be much use if it didn’t provide an answer to big questions. The answer to this question is: God cursed the parts of his creation that man interacts with (Genesis 3:17-18). The whole of creation is subject to the same tension that believers feel, between the new life they have been given, on the one hand, and the lusts of their old flesh which is fallen and deserves to rot, and one day will do so. That is Romans 8:19-23.

Yes – God delivered his newly created world into the hands of Satan — the ‘prince of the power of the air’ Eph 2:1–2); ‘the god of this world’ (2 Cor 4:4) etc; — and the freedom from bondage that awaits it is freedom from him.

So, this is different to saying that God sent a particular tsunami, earthquake, or pandemic that we must suffer as being from his hand.

I think at the root of the misunderstanding (as ever with these things?) is what I believe is a theological misunderstanding. Anton (I think it was you?) in a recent blog commented that death is a punishment from God — it would follow that we must accept that suffering is a punishment from God and thus we need to work through the ‘meaning’ of our own suffering and that of others.

In Eden death came about as a consequence of an interaction with Satan — and Paul (as appears to be the academic consensus) in Romans 7:7–11 is seen to be speaking as if he were Adam in Eden and there he says that Satan killed him — i.e., not God.

Greg Boyd and Michael Heiser both fine (non-Confessional) biblical theologians have written comprehensively about this, demonstrating from Genesis to Revelation the direct role cosmic evil plays in human suffering.

It led them both to embrace a more open theism than I think Scripture allows — I suggest it is safer to leave first causes in what I describe as the ‘Deuteronomy 29:29 box’.

But nonetheless in essence I agree with them that we should not speak as if God is himself willing untold (often chaotic) suffering and death on millions with COVID, ‘natural’ disasters’, and unnumbered diseases.

Much has been written over Open Theology and the attributes god of Open Theology, including Boyd and push-back against his espousal of Open Theology.

Here is a link to a short push-back from Andrew Wilson:

https://thinktheology.co.uk/blog/article/responding_to_open_theism_in_fourteen_words

Geoff, just wondering if you or anyone has come across something like ‘responding to “calvinism” in fourteen words’? How many of the ‘words’ were the same?

🙂

(Yes, to your 3.19pm comment, Anton)

BS.

Even as this follows through on Colin H’s comment on Open Theology and Boyd, in Colin’s comment on the article, do you have anything of substanstance to contribute, even in a link, in response to (1) the article itself and/or (2) Open theology as espoused by Boyd and others?

I hadn’t realised that Andrew Wilson was/is a so called “Calvinist”. He might be surprised to learn that he is.

What is a Calvinist, according to your understanding?

Have you read anything of his writings.

What is your understanding of the sovereignty of God?

Hi Geoff.

You ask:

‘What is a Calvinist, according to your understanding?’ — TULIP. But may also include things like ‘double predestination’, ‘no molecules moving outside God’s will’, too quick a distinction of ‘God’s permissive will’, an over-reliance on ‘proof texts’.

‘Have you read anything of his writings.’ — Andrew Wilson’s? Some.

‘What is your understanding of the sovereignty of God?’ — orthodox.

I don’t know whether Andrew Wilson considers himself a ‘Calvinist’ or not. I might assume from what he said — that he would count himself among the ‘Reformed’ and that he distinguished ‘Reformed’ and ‘Arminian’ that he might think of himself that way. That might be a wrong assumption of course. But that is not the point.

The ‘words’ given in the blog post do not come anywhere near ‘*answering’* the questions of Open Theism. So they are not that helpful to people thinking through those questions either themselves or with other people. I am sure that in some quarters similar ‘arguments’ against Calvinism would get you fired not because of the arguments themselves, but because you raised them.

BS, Again nothing of substance: Irrelevant to the topic or open theology of Boyd and others as raised by Colin H. It is merely

quarrelsome trolling, of my comments just for the sake of it. Bye!

Hi Geoff.

Nothing of substance?

“You [Geoff] ask:

‘What is a Calvinist, according to your understanding?’ — TULIP. But may also include things like ‘double predestination’, ‘no molecules moving outside God’s will’, too quick a distinction of ‘God’s permissive will’, an over-reliance on ‘proof texts’.”

Geoff, this was a plea to NOT dismiss Open Theism (Pinnock, Sanders, Boyd and Co) so blithely with a few statements that did not address what these people were saying. A more helpful resource might be

https://www.patheos.com/blogs/rogerolson/2010/08/open-theism-a-test-case-for-evangelicals

This would also would be relevant to your desiringgod reference below.

It was not intended as a personal slight.

I disagree with open theology, but I also believe that the conventional view it challenges is wrong.

Does God have foreknowledge? No, says open theism. Yes, says mainstream Christian theology. I accept the criticisms of each by the other. I take my resolution from the Trinity. God the Father is indeed above time (which, like space, He created), but God the Son steps into space, and therefore into time. (That ‘therefore’ is thanks to Einstein, who explained that time and space are inter-related.) A Bible verse backs up this explanation. In Mark 13:32, Jesus says that not he, but only God his Father, knows the date on which he, Jesus, will return -at the time he spoke these words while incarnate, anyway.

Anton, One thing I love about Ian’s blog is that I will read a comment and wholeheartedly agree with it – as I do here – and then a few posts later find myself wondering what the same poster is saying – as I do with your comments on rain and floods (see below!) Perhaps I am just a mongrel Christian?

Jon, I was being rather elliptic because I am sceptical that human agency is warming the globe to a dangerous extent, but I don’t wish the subject to take over the thread.

Sorry, link should be:

https://www.patheos.com/blogs/rogereolson/2010/08/open-theism-a-test-case-for-evangelicals

Geoff, I agree with this statement on God’s sovereignty:

“God rules the world in such a way as to allow for creaturely input. [Biblically] there are not two sets of texts — one affirming exhaustive sovereignty and the other affirming human freedom. That would be a contradiction. We are not asked to believe that God exercises all-controlling sovereignty and still holds human beings morally responsible. The Bible is coherent and the contradiction is imaginary. All-controlling sovereignty is not taught in Scripture. There may be mysteries that go beyond human intelligence but this is not one of them. One can hold both to divine sovereignty and human freedom because sovereignty is not all-controlling. The Bible, not rationalism, leads to this conclusion.”

We need to read the Bible as it is, not as an unsorted collection of proof-texts.

God cursed the parts of his creation that man interacts with (Genesis 3:17-18).

That is not, in my opinion, a satisfactory explanation, not least because the original earth (landmass) was destroyed in the Deluge (Gen 6:13, 9:11), together with the ‘ground’ that formed its surface. The new earth which took its place was not cursed. Seedtime and harvest, God promised, would never cease. Noah planted a vineyard, which was fruitful enough for him to get drunk on the produce. The Jordan Valley was likened to the garden of the Lord (Gen 13:10), so certainly wasn’t cursed. Nor was the land to its west, flowing with milk and honey. Much of western Europe could be described in similar terms. While some parts of the earth today are barren or at least difficult to work, many parts are fertile, and in terms of yield per acre food production has never been higher (thanks to fertiliser, plant breeding and mechanisation).

Do you believe the curse on woman, of particularly painful childbearing, was lifted after the Flood?

Why does God allow suffering? Read the Scriptures, simples.

Romans 8:22 For we know that the whole creation groaneth and travaileth in pain together until now.

8:23 And not only they, but ourselves also, which have the firstfruits of the Spirit, even we ourselves groan within ourselves, waiting for the adoption, to wit, the redemption of our body.

recent deterioration of weather conditions in the UK leading to severe storms and flooding

What deterioration? See the links at

https://notalotofpeopleknowthat.wordpress.com/tag/extreme-rainfall/

There has always been flooding, and any worsening recently is due to reduced river dredging (as in the Somerset Levels flooding a decade ago) or irresponsible house-building on flood plains.

This website uses some odd metrics. Over, rainfall has increased in the UK by around 10 to 15% over the last 100 years, and this is happening more in the winters, where some regions have had a 30% increase. That is very significant in terms of change.

Please be more specific both in your challenge to the link I gave and in the statistics you quote.

At the Met Office website you can find “climate averages” for those places which record the weather. They have 30 year averages for those places (many of them airports or airfields) from 1961. For my local place, Bournemouth Airport (aka Hurn), average annual rainfall for 1961-1990 was 790.08mm. For 1991-2020 it was 876.64mm, just under an 11% increase. The moving average rises steadily if look at the period starting in ’71, and ’81. Also, the daily high temperature, averaged over the year rose from 14.13 to 15.14.

Benson, in south Oxfordshire and notable as the coldest place in southern England on cold nights, the corresponding figures are 604.68/633.74mm and 13.58/14.75.

Bournemouth Airport received a lot of rain over the months from October ’23 to May ’24. Here are the numbers, with the average for the month for ’91 to ’20 in parentheses):

Oct: 184.2 (100.65)

Nov: 217.5 (107.57)

Dec: 135.8 (104.23)

Jan: 127.6 (96.04)

Feb: 136.6 (67.19)

Mar: 105.5 (62.42)

Apr: 85.0 (57.87)

May: 97.2 (49.02)

(Since our rain-carrying weather comes mostly from the South West, it is perhaps not surprising that inland places to the North West, or West of high ground such as Dartmoor or the Welsh hills would experience less of an increase. The increase tends to fall on the coastal areas first.)

I meant North East of the higher ground, of course.

I trust the rainfall figures you give but they are a long way from making the case that Ian wrote. The temperature figures have probably been homogenised, i.e. ‘corrected’ for urban heat island and other effects, and the corrections always seem to have the effect of making the temperature rise from a century ago to the present appear greater. I don’t trust that.

Anton

The reality is that you don’t have to “believe” in situ observation records. You just have to think back to science at school – every kid learns how the greenhouse effect works.

Or you can simply understand that if you change the chemical composition of a substance then you also change its properties.

Peter,

When you throw temperature data into global warming models there might be reason to use a different temperature from the value actually recorded – if a particular weather station was put up in a green field but has since been built round, causing an Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect, which should be compensated for.

One way to correct for UHI heating is to find weather stations near the one in question which are still in fields, calculate the average warming at those, and use that figure to correct the figure at the weather station that became urbanised. This procedure is called data homogenisation.

BUT homogenisation is often done wrongly, and makes the warming look bigger. Homogenisation should identify the extent to which each individual station has been urbanised, and when. Instead, software is often used, e.g. a ‘majority voting’ algorithm among stations in the same region. But if there are more urbanised than green-field stations, the urbanised ones mistakenly add the UHI heating to the green-field data. That makes recent warming at the green-field stations appear bigger. Or the correction needed to cool data from an urbanised station is applied from before the date at which it was built around. That makes the past look cooler and makes subsequent warming look bigger. Or no correction is applied to urban data, causing UHI heating to be assigned wrongly to CO2.

Many webpages of older temperature observations have been replaced by ‘corrected’ ones at the same web address. “We…. do not hold the original raw data but only the… homogenized data” – website of the Climatic Research Unit (CRU) at the University of East Anglia.

If in a school science experiment, I had

* used altered data to reach my conclusions

* thrown away the actual data

* said only in small print that I had altered it, and

* used dubious methods to make the alteration

then my physics teacher would have thrown me out of the laboratory with 0/10. Yet that is happening in climate science. Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?

You just have to think back to science at school – every kid learns how the greenhouse effect works.

Really, Peter? To understand the greenhouse effect you need to be able to calculate the average surface temperature of the earth in the absence of any atmosphere, using Stefan’s radiation law and the temperature of the sun and the solid angle which the earth subtends at the sun. The answer (averaged over latitudes) is about -23°C.

That’s in the right ballpark, but a bit cold. That’s because of the atmosphere. Think of it as like a glass cover above the earth. It lets through most radiation, but the gas molecules of the atmosphere absorb a little. The atmosphere then (re)radiates this energy in all directions – so equally upwards and downwards.

Half of the radiation that the atmosphere absorbs from the sun, it radiates back to space. That makes the earth-atmosphere combination (mainly the earth) cooler than without an atmosphere. Half of the radiation that the atmosphere absorbs from the earth radiating, it radiates back down. That makes the earth warmer. But the upgoing radiation is mostly at different wavelengths from the downcoming radiation, and our atmosphere absorbs more of it. So the warming effect is stronger than the cooling.

This is the ‘greenhouse effect’. It warms the earth by about 30°C, to an average of about 7°C. (Bad name, as warming in greenhouses isn’t about differing wavelengths; it is because warm air, heated by contact with the sun-warmed earth inside the greenhouse, rises but is trapped by the glass roof.)

How does the greenhouse effect work, at molecular level? The effect is about absorption of radiation by the gas molecules of the atmosphere. How do they do it? Their molecules can vibrate at specific frequencies – imagine the elementary particles in a gas molecule as attached to each other by springs.

Radiation has a frequency and a wavelength (for radio, VHF = short waves). You can calculate one from the other: if you halve the wavelength of radiation moving toward a molecule at the speed of light then you double the number of wavecrests that reach it in a given time – i.e. you double the frequency.

Radiation at a wavelength whose frequency matches a natural wobble frequency of the molecule is absorbed by the molecule and makes it wobble. The radiation doesn’t pass through the gas. Later, the molecule stops wobbling by emitting radiation at the same frequency, but in an arbitrary direction.

So you can think of the atmosphere as a stained glass cover above the earth, coloured because it absorbs different wavelengths (colours) selectively. Various ‘greenhouse gases’ contribute to greenhouse warming in the earth’s atmosphere.

That is the simplest possible proper non-mathematical explanation of the greenhouse effect. Take anything away from it for simplicity’s sake and you get a misleading version. The idea that every kid learns that in school science lessons is nonsense.

if you change the chemical composition of a substance then you also change its properties.

Of course. What relevance has that?

I’m going, I’m afraid, to write in general terms, but could back up these statements. Climate is always changing, but it does seem like mankind is contributing to the current changes. The question is, by how much? It has become a political issue (like some theology) and discussions unfortunately veer to the extremes, with some dubious statistics produced (such as the exaggerated hockey stick.) In my 40 odd years (very odd at times) mainly spent playing with rainfall and floods I’ve come across some interesting cases. There seems to be a 30-year cycle of low and high rainfall. In Southern Africa, the Lesotho Highlands water scheme was under designed as it was conceived at the end of a wet period. In the UK, the Autumn 2000 floods seem to be at the start of a wet period, the design rainfalls in use were too small and hence a lot of flooded housing estates. In NE Thailand, they cut the forests down for rice, and the rainfall dropped dramatically. In Hong Kong rainfall has increased, probably due to pollution and aerosols from the rapidly developed cities on the mainland. (I read a fascinating paper suggesting that the weather was better in Tokyo at the weekend as they turned the aircons off.) Add a bit of global warming, and solar heating cycles and it can be very difficult to see exactly what is going on!

Better get back to the theology……

Jon

As with a lot of things long term, specific things are harder to forecast (will a red car drive past my house next monday?) than more general things (the average daily number of cars passing my house in a year).

Rainfall patterns are harder to forecast than global mean temperatures, but we can see that in most places in the globe rainfall patterns are rapidly changing. One of the concerning things about our climate change is that it is far more rapid than natural changes.

Anton

That’s not how climate models work.

Climate forecasts don’t use observations. They are just using known inputs (like radiation from the sun) and then different scenarios for greenhouse gases.

I am pretty sure homogenization of past observations (which don’t go into climate forecasts) doesn’t include removing urban impacts…because they are a legitimate part of the environment, what they do do is remove sudden jumps in the bias which is usually caused by changing the instrument for recording in some way.

Climate forecasts don’t use observations? Nonsense, they use observations to estimate the parameters in their models. But the big problem is whether the model is correct in the first place.

As for homogenisation…

Geophysics professor F.K. Ewert found that NASA altered data back to 1881, making subsequent warming look bigger – especially in the Arctic, which isn’t urbanised:

principia-scientific dot org/nasa-exposed-in-massive-new-climate-data-fraud/

Where stations are sparse, adjustments may come from stations in distinct climates, e.g. Tasmania from Melbourne!

joannenova dot com dot au/2019/10/homogenisation-the-magical-system-which-uses-thermometers-in-victoria-to-correct-the-temperature-in-tasmania/

In Paraguay, both urban and rural weather stations were adjusted, exaggerating recent warming:

notalotofpeopleknowthat dot wordpress dot com/2015/01/26/all-of-paraguays-temperature-record-has-been-tampered-with/

Multiple examples of homogenisation that make the warming look bigger:

www dot manhattancontrarian dot com/blog/tag/Greatest+Scientific+Fraud

Ian

Can I suggest you get a guest blogger in who is a climate scientist to talk about this?

Theologians can speculate until the cows come home, but it would be far better to have some solid information than speculation.

Well, the data is out there. And climate change isn’t actually the subject of this post.

Ian

The average reader of your blog doesn’t understand the data.

I think it would be interesting to have some subject specialists write for your blog.

Ian.

When a hard question in science is not settled, differing schools of thought arise. As more data comes in and better theories are worked out, one school eventually emerges as correct and wins further grant applications, jobs etc. Other schools dwindle as their members change field or leave academia. Few openly change their mind, because it is hard to accept that you have wasted years of your research life.

Science can be thrown off course for longer if a school that later turns out to be incorrect gains – by political means – all of the grant money and vacancies.

From summer 1988, US funding for climate science rose 15-fold in 6 years after an alarmist briefing to Congress at which one speaker had jinxed the air conditioning (Jim Hansen of NASA). Politicians trusted what scientists told them. Science faculties and job applicants understood that recruitment was in response to the alarm, and knew what proposals and viewpoints would (and wouldn’t) win grants and jobs. Other Western nations followed. At that time, no warming effect other than greenhouse gases was known apart from a short-term solar cycle and the earth’s orbit, both possible to account for. So scientists included only CO2 in their computer models. More effort then went into matching the models to the data, doubling down on CO2 as the ‘master switch on the dial’ of global warming.

So claims of ‘scientific consensus’ (97%?) prove nothing. In fact more than 440 papers sceptical of the CO2-master-switch papers were published in 2019 alone:

https://notrickszone.com/2020/01/30/over-440-scientific-papers-published-in-2019-support-a-skeptical

People who see best what’s going on are physicists working in other fields – because as physicists, they can educate themselves to read the technical climate literature, yet they haven’t been indoctrinated into the CO2-only model. It’s your blog, so you can invite guest posts by whoever you like. I’d gladly have dialogued with the late Sir John Houghton, a serious Christian who led the IPCC in its early days, but today the CO2 model has been found to have grave problems which the climate establishment ignore.

Open Teology: here is the link to a full, free book-lentgth response to Boyd, Pinnock et al. It is a link highlighted in Andrew Wilson’s short push-back.

https://cdn.desiringgod.org/pdf/books_bbb/books_bbb.pdf

Where is the Wilson push back?

It is in his linked response in my comment @1:29 pm. ‘Think Theology’ from 2017.

‘Responding to open theology in 14 words.”

It doesn’t set out to be fully developed argumentation.

In addition, it is implied in his link to the gospel coalition free book – length resource.

Crikey I cannot find that. Can’t you just post a link?

Thought I had, embedded in

my comments.

But, I’ll try again when I’m at home.

Link is here:

https://thinktheology.co.uk/blog/article/responding_to_open_theism_in_fourteen_words

Meanwhile back at the Farm…

Mark Broadway writes: Does suffering matter? This is a question that many will have tried to answer, scouring philosophy textbooks from the safety of the library. Perhaps more importantly, in times of distress and pain, a more poignant question arises from the depths of a heart: does my suffering matter?

Broken Planet (Sharon Dirckx, IVP 2023) fruitfully engages with a particular category of suffering—that which arises from natural disasters.

Jesus has demonstrated that He is above nature and is master of any storm.

Nahum [1:3] informs “The LORD is slow to anger, and great in power, and will not at all acquit the wicked: the LORD hath his way in the whirlwind and in the storm, and the clouds are the dust of his feet”.

The Psalmist {Ps.18:9 } He bowed the heavens also, and came down: and darkness was under his feet. And he rode upon a cherub, and did fly: yea, he did fly upon the wings of the wind.

He made darkness his secret place; his pavilion round about him were dark waters and thick clouds of the skies.

So much hot air is produced when discussing the weather.

Perhaps an event in Paul’s life might address our point [Acts 27]

During a 14 day storm, a typhoon , called Euroclydon; “Typhon”, in Pliny, means the hurricane (ἐκνεφίας, the hurricane caused by clouds meeting and bursting) descending like a thunderbolt, the especial bane of sailors:

Acts 27 serves as a compelling narrative of faith amidst turmoil and divine protection. Paul’s calm and leadership, even as a prisoner, are testament to his unshakeable faith in God’s promise. His voyage becomes a physical manifestation of the spiritual storms that believers may face, but it also underscores God’s providential care and the reassurance that He is with us, even in the most tumultuous of storms.

Paul, a prisoner, became Master of the ship because the Master of the storm spoke to him.

To what purpose? He spent three months on Malta healing and preaching

After being shipwrecked, Paul and the others find themselves on Malta, where the locals show them great hospitality. When Paul is bitten by a poisonous snake yet remains unharmed, he is considered a god. He further astonishes them by healing Publius’ father and others on the island.

When discussing the weather don’t forget the Sovereignty of God.

Commenting on troubling episodes an associate remarks “It came to pass.”

Job didn’t get many answers about the purpose of suffering but he did get a mighty revelation of the Sovereignty of God.

Natural ‘disasters’ are inevitable on any planet made of the same ‘stuff’ as earth. Do we define an event as a ‘natural disaster’ only if humans are hurt or killed during it, or just any natural event such as an earthquake, hurricane, mudslide or worldwide virus pandemic?

Clearly God has the power to create a natural disaster, as I suppose does satan. But Im not convinced either do very often. It would be the exception rather than the rule. Rather, per above, they are usually just the natural consequences of living on this planet. But of course we humans can be the direct cause of ‘natural’ disasters. I recently listened to a Radio 4 programme about a young man who, after a huge mudslide caused mayhem and destruction, including the deaths of his adopted family, was motivated to find an alternative fuel to wood as the cutting down of trees to supply wood as fuel was the main cause of the devastating mudslide. His idea was to use coconuts which were part of the local economy, to make into fuel, thus reducing the need for wood and avoiding tree felling.

And whilst others dont accept it, I do accept that current climate change is largely caused by humans, and while it is silly to say such and such a storm was caused by climate change, the frequency and perhaps intensity of such weather phenomena may very well be the result of general increased overall temperatures.

Jesus said when a bird falls to the ground, He is aware of it, indicating that God is aware of literally everything that happens. But He didnt say God killed the bird or was in any sense the cause of its downfall. He allowed it, as He more often than not allows death and suffering all around, whether animals or humans. We may wish it otherwise, but that seems to be the reality, part of the reality of living on this planet. I dont take Genesis 1 and 2 literally, but even if you do the impression I get is that the garden was like a protected area from the outside world, something of an oasis. It was not the norm on planet earth, as the humans found out after they left.

Does God ever ‘will’ suffering? Perhaps, in some circumstances – Paul alludes to this re his comments on some believers who were abusing communion in some way, and of course we have the example of Ananias and Sapphira in Acts. But He certainly ‘allows’ most of it, even if He occasionally steps in to end it, such as through a gift of healing.