One of the many reactions to the result of the General Election earlier this year was a renewed call for electoral reform. The reason for this can be shown by a simple analysis of the number of votes needed for each seat in Parliament for the different parties:

One of the many reactions to the result of the General Election earlier this year was a renewed call for electoral reform. The reason for this can be shown by a simple analysis of the number of votes needed for each seat in Parliament for the different parties:

| Votes | Seats | Votes per seat | |

| Con | 11,162,553 | 325 | 34,346 |

| Lab | 9,236,878 | 229 | 40,336 |

| Lib Dem | 2,359,368 | 8 | 294,921 |

| UKIP | 3,830,029 | 1 | 3,830,029 |

| Green | 1,138,445 | 1 | 1,138,445 |

| SNP | 1,454,436 | 56 | 25,972 |

This is very clear indication of the system falling well short of its claim to be a ‘representative’ democracy, and in the election itself it means there is disproportionate reward for those who cunningly target marginal seats or marginal interests, rather than those who give proper account for their policies or manifestos. It has been pointed out that Labour’s victory in 1997 was similarly unrepresentative—but the disparity between the bottom four parties is particularly shocking, and contributes to the fact that we have never actually had a Government that the people want, as measured by their behaviour at the ballot box:

Let me explain. In Britain today, we have a centre-left majority who want this to be a country with European-level taxes, European-standard public services and European-level equality. We have had this for a very long time. Even at the height of Thatcherism, 56 per cent of people voted for parties committed to higher taxes and higher spending. But the centre-left vote is split between several parties – while the right-wing vote clusters around the Conservatives.

Rather predictably, all interest in reform has been swamped by reports of the death of the Labour party, even if some think the reports are exaggerated. But the concerns should not be forgotten, since this election was the most disproportionate in UK history.

- 50% of votes in the election (15m) went to losing candidates, while 74% of votes (22m) were ‘wasted’ – i.e. they didn’t contribute to electing the MP

- 2.8m voters were likely to have voted ‘tactically’ – over 9% of voters

- Under a more proportional voting system – the Single Transferable Vote – the Conservatives would have won 276 seats to Labour’s 236, while the SNP would have secured 34, UKIP 54 and the Lib Dems 26. The Greens would have won two more seats – in Bristol and London

- The ERS was able to call the winner correctly in 363 of 368 seats – a month before polling day – due to the prevalence of ‘safe seats’ under First Past the Post

- This election saw an MP win on the lowest vote share in electoral history – 24.5% in South Belfast

- 331 of 650 MPs were elected on under 50% of the vote, and 191 with less than 30% of the electorate.

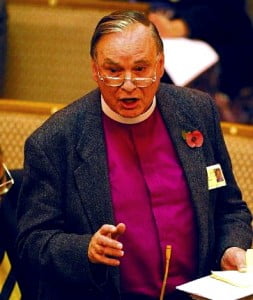

In a new Grove booklet, Colin Buchanan, formerly Principal of St John’s Nottingham and Bishop of Woolwich, makes the case for reform. Though Colin is best known as a liturgist, he has always taken a keen interest in elections and voting, and for many years was nnorary President of the Electoral Reform Society. This is an area where, just for once, the C of E leads the field; it has practised fair voting in its central bodies since 1920, and uses Single Transferable Vote (STV) in the elections to General Synod which are happening later this month.

In a new Grove booklet, Colin Buchanan, formerly Principal of St John’s Nottingham and Bishop of Woolwich, makes the case for reform. Though Colin is best known as a liturgist, he has always taken a keen interest in elections and voting, and for many years was nnorary President of the Electoral Reform Society. This is an area where, just for once, the C of E leads the field; it has practised fair voting in its central bodies since 1920, and uses Single Transferable Vote (STV) in the elections to General Synod which are happening later this month.

Colin first explores why our current system, First Past the Post (FPTP) remains in place—essentially, because those in power would only be in power under this system, so have a vested interest in defending it. Through an analysis of the results of the General Election, he highlights eight injustices in the present system: disproportionality; randomness; using a bad system to get a ‘good’ result (stability); tactical voting; disincentives to run for seats; wasted votes; misrepresentation; a closed book of candidates. This is a long list of problems—though for me the most serious is misrepresentation. As Colin explains (p 19):

It is basic to Westminster thinking that there should be single-member constituencies. Thus, when the result is declared in a constituency, the newly elected member not only pats their own party on the back, but charmingly expresses the intention of serving the whole constituency, representing in Parliament all the inhabitants, whatever their own views or voting habits have been. We can quickly admit that any responsible MP will take up individuals’ needs in the constituency without regard to their political outlooks, but that, I submit, is minimal representation’ and was only minimally in view by the electors.

The underlying moral issue in representation is that the ‘losing’ voters, not least those who have lost consistently in the same constituency for 40 or 50 years, have as their member one who in no way represents their outlook or policies, but expresses in Parliament and around the country a position which they abhor, one contrary to their views. Any system based on single-member constituencies is open to this frustration; but in a safe seat the defeated voters remain defeated indefinitely, without hope of changing their representation, and in a marginal constituency there is a further element of make believe and deception in any claim that the voters are represented by a member elected by 40% of the votes cast. We need another hard look at single-member constituencies.

One of the supreme ironies of resistance to electoral reform is that, if we were to move to STV, it would also address another constant irritation in the current system—the tension between an individual candidate and the party they represent. Many electors either like someone’s party, but find them unsatisfactory, or conversely warm to a person but don’t agree with the person’s party policies. STV offers a way out of this dilemma, as Colin sets out in the final chapter. If (for example) a four-seat constituency, where the four are elected by STV:

- Each candidate can be carefully placed into the preferential order—if the one labelled ‘1’ is eliminated as a no-hoper, the vote transfers to ‘2.’ Instead of all candidates but one being labelled ‘totally unwanted,’ each is now wanted in this carefully enumerated pref- erential order. The voter does not vote against any candidate—save by locating the seriously unwanted at the bottom of the preferences.

- There is therefore no possibility of votes being split, and the whole concept is mercifully dismissed from consideration.

- There is an end of tactical voting. Instead, the voter expresses honestly the actual order of preferences they hold. There is no more doing evil that good may come.

- Safe seats are virtually doomed. Where four seats are to be decided, in the outcome at least two parties will elect candidates, and quite possibly three or four. It follows that there are bound to be contests to change the distribution and thus, although one or two members may look fairly safe, every vote is likely to count in deciding the less certain third and fourth places. The voter has therefore the incentive to vote. No vote will be wasted.

Major parties have to run two candidates, perhaps three (and will do themselves no harm if they run four). Thus supporters of those parties can choose between the candidates themselves, and the individual gifts, style, bearing and outlook of each has weight in the voters’ arranging of their preferences. Men and women, black and white, old and young, professional politicians and gifted amateurs, all come into account as a party nominates its candidates—the caucus shortlists, but the voters then decide.

Major parties have to run two candidates, perhaps three (and will do themselves no harm if they run four). Thus supporters of those parties can choose between the candidates themselves, and the individual gifts, style, bearing and outlook of each has weight in the voters’ arranging of their preferences. Men and women, black and white, old and young, professional politicians and gifted amateurs, all come into account as a party nominates its candidates—the caucus shortlists, but the voters then decide.

There is a powerful case for Christians to campaign on voting reform as a justice issue.

Keep your leaders up to the mark—we hold the high moral ground in electoral procedures. We should be prophesying from it.

You can order Colin’s Grove booklet online at the Grove website and it will be delivered post free in the UK. Order two and send one to your MP. Order five and you get a discount!

Follow me on Twitter @psephizo

Much of my work is done on a freelance basis. If you have valued this post, would you consider donating £1.20 a month to support the production of this blog?

As I wrote four years ago, the ethics of this aren’t quite as simple as the proponents of PR want to make out.

http://www.peter-ould.net/2011/02/02/certain-voting-systems-are-not-morally-superior/

Thanks Peter—very interesting. But Colin points out the actual injustices in the present system with some very clear examples, and so does I think make a moral case.

One of the strengths of the booklet is that both the current and a future, STV, four-candidate scenario are both worked through.

There is something morally problematic, for example, about the current existence of safe seats. There is little accountability and little sense of representation in terms of policy. That does appear to me to be morally inferior in a system which claims to be representative.

The indirect election system of the Church is also flawed. General Synod lacks democratic legitimacy. It does not represent ordinary church members and gives disproportionate power to bishops.

I agree with Peter Ould that the German additional vote system (also used in New Zealand, and locally in Scotland and Wales) is superior to STV. STV is supported by electoral reform societies because of its theoretical merits, but as seen in Ireland and Australia, in practice, it can lead to unwieldy lists of candidates (one Australian Senate election had 80+!), doesn’t noticeably increase representatives’ independence, and is still disproportionate nationally.

This theoretical approach helps explain why voting reform’s yet to gain traction in most of the Anglosphere. It’s a trend for the twitterati; to succeed, it has to become a mass-movement, as the fight for a universal franchise did. When it became a mass-movement, in New Zealand, voting reform won.

Although I support electoral reform, I accept that fairness can be achieved by an alternative route: increasing the independence of legislators. If they’re not commanded by a party, but by the people in their districts, then the national share of the vote doesn’t matter so much. To implement that, there needs to be reforms like compulsory open primaries, an absolute right of recall, and a right for constituents to pass a binding vote to force their representatives to, well, represent them.

Beyond all that, whatever system’s used, if the people are sovereign, there should be a means to bypass legislatures altogether via referenda, as can be done in the Western states of the union, and in Switzerland, surely the most democratic country on earth.

Thanks for this article, Ian – I like that you’re engaging with different issues even if I don’t always agree!

Of course these were issues that came up in the referendum a few years ago. Whilst some of the issues and complaints about our current system have some validity there are surely ethical problems regarding STV as well – especially that it effectively gives supporters of minority parties effectively 2 (or more) votes, as they use their ‘second chance’.

If you’re, say, mainly a UKIP fan but with Tory sympathies, you could vote UKIP as first preference but then have a ‘back-up’ vote for the Tories which would go through to the final count. The same could be said for fringe parties on the left.

On the other hand if you’re a supporter of the main parties you effectively just have one vote, because your party will probably survive until the ‘final shootout’. No ‘second chance’ for you – yes, I guess you could give a second choice to a fringe candidate but they’ll be knocked out in the earlier rounds.

So in my view STV is ethically biased against supporters of the main parties, and as a related drawback I’d argue it promotes a less mature political system, where ‘one issue’ parties and politics get more of a voice than they probably deserve. A common assessment was that the Conservatives got that surprise victory in May not because they were wildly popular, but because in the voting booths, faced with a single ‘X’ to write and a family to bring up, floating voters held their noses and voted Tory as the soundest economic team . For me that’s mature decision-making, accepting that the major parties are a coalition of factions, and that voting decisions sometimes has to be ‘on balance’ rather than ‘precisely what I want’.

But what would the voting patterns look like, if angry people could ‘sound off’ with protest votes all the time? One final thought is that the voting statistics you show aren’t really valid, because the system would skew the voting patterns.

Peter, Germany is, by any measure, a “mature” democracy, are Switzerland and the Scandinavian countries. All are models of stability and efficiency. Switzerland is not famed for its radicalism. All use proportional systems.

It’s possible to recognize that FPTP forces you to choose a lesser evil without liking it, or believing it to be the best system. In proportional systems, people still have to compromise, as parties rarely win a majority. Difference is, people can vote for what they support, and the compromise is built from a wider base. Power is dispersed and diluted. FPTP leads less to “coalitions” than one faction taking control of a party, then getting a majority of seats on a minority of the vote. This winner-takes-all system leads not to mature compromise, but immature back-biting and infighting, followed by a belief that the winner has the right to impose their will.

I do agree with your point about STV unfairly benefiting supporters of minority parties, one of the many reasons I don’t believe it to be the best alternative to plurality voting.

Hi James,

I agree that a mature democracy can emerge from PR systems – I think I was focussing on STV in particular, for the reasons I mentioned.

Interesting to reflect that General Synod works to a STV system – I’m a clergy voter in a fairly MOTR diocese so might spice things up by voting for my local FiF candidate as 1st pref, then the Reform guy as #2 member, before choosing the person I actually want to win as my 3rd choice 🙂

STV or AV are a wonderful alternative to the current system. Sadly, when the LibDem’s sold their soul to the Conservatives in order to give us the opportunity for electoral reform, the electorate chose to bloody the nose of Nick Clegg for not standing up to the Tories, rather than embracing the change that could have been brought about.

Will we ever have a true democracy when the media is almost universally in the control of right-wing oligarchs?

Yes, Clint, I think you are right. Mind you, the AV proposed had its faults, and it would have been much better to have offered STV.

Do you include the BBC in your list of oligarchs?