The lectionary gospel reading for Advent 2 in Year A is Matt 3.1–12, and it contains many foundational themes of eschatology, the coming of God, and judgement, which set us up nicely for thinking about Advent not as the build-up to Christmas, but (as it should be) thinking about the Last Things.

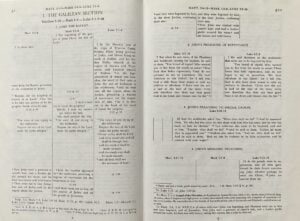

This is one of those passages where it is particularly informative to compare the gospel accounts side by side; you can do this with a printed text like Throckmorton’s Gospel Parallels, or online using something like this site from the University of Toronto. The online version is convenient, but the print edition highlights differences more clearly in its layout, as you can see here (click to enlarge). Just looking at the shape of the text, you can see the different emphases in the three Synoptic accounts.

This is one of those passages where it is particularly informative to compare the gospel accounts side by side; you can do this with a printed text like Throckmorton’s Gospel Parallels, or online using something like this site from the University of Toronto. The online version is convenient, but the print edition highlights differences more clearly in its layout, as you can see here (click to enlarge). Just looking at the shape of the text, you can see the different emphases in the three Synoptic accounts.

We can see immediately the different interests of the gospel writers. Luke locates the beginning of John’s ministry in the larger world of the Roman empire, whilst the Fourth Gospel doesn’t explain either John’s ministry or Jesus’ baptism, but assumes you already know about it from reading the other gospels. There is an interesting contrast between Matthew and Mark’s ordering of elements (which I am not sure commentaries pick up) which is striking since, in other respects, Matthew follows Mark quite closely. Mark introduces John the Baptiser in this order:

OT prophecy—John’s preaching (and baptism)—the people’s response—John’s appearance

but Matthew introduces the elements in this order:

John’s preaching—OT prophecy—John’s appearance—the people’s response (and baptism)

It is characteristic of Matthew to describes something, and then explain how this fulfils OT prophecy, as we have seen (or will see) in the nativity account. He appears to want to emphasise John’s appearance up front, which (of course) identifies him with Elijah.

Matthew’s opening phrase ‘In those days…’ is very general, and follows the pattern of Mark’s ‘In those days…’ with reference to Jesus in Mark 1.9. It sits rather oddly in Matthew’s account, since he has already been talking about the events around Jesus’ birth, and these events are now decades later. (We only know from Luke that John and Jesus are about the same age.)

Although Matthew introduces John as ‘the baptist’ (different from Mark, ‘the baptiser’), his emphasis is constantly on his preaching. He appears ‘in the wilderness’, which is not just a physical location, but one pregnant with theological significance, both for the people as a whole and for John himself. The wilderness was the scene of the Exodus wanderings, a period of testing and refinement as well as a period of the presence of God with his people. But it is also the place of new beginnings when the people have strayed from God, a place where God will once more woo and win his people (Jer 2.2–3, Hos 2.14–15, Ezek 20.35–38). And it is the place through which God will call his people home from exile in Is 40.3, which Matthew then cites. For John, the wilderness is also the home of Elijah, whose clothing he also wears (see 1 Kings 17.3–7 and 2 Kings 1.8). Locusts were a common and practical food source, and are still eaten in the region—but they also signify the diet of someone who eats what God has provided, rather than food he has worked for, echoing the promise of God that the land will be ‘flowing with milk and honey’, things that you gather rather than work for (in contrast to the sowing and harvesting of grain).

Matthew consistently records Jesus and others talking about the ‘kingdom of the heavens’ rather than the ‘kingdom of God’ as found in Mark and Luke. It has been argued that this is Matthew’s Jewish tendency to avoid using the name of God—but he does use the phrase ‘kingdom of God’ on occasion (as in Matt 12.28, 19.24), and elsewhere does not avoid ‘God’. So it is perhaps merely stylistic, though it does emphasis the divine origin of all that will happen, in contrast with other more political expectations of the Davidic messiah.

The nature of the ‘kingdom of God/heaven’ has been debated at great length in scholarship in the past, though there is less debate about it currently. The consensus is that, rather than referring to a territory or an object, it is really referring to the dynamic nature of the reign of God, based on the OT idea of God as king of both his people and the whole earth. It is central to the teaching and ministry of Jesus in the Synoptic gospels, and the hope for the kingdom of God (almost never abbreviated simply to ‘the kingdom’ in the gospels) has become central to Christian prayer.

Matthew’s summary of John’s (and Jesus’) declaration ‘The kingdom of heaven has arrived’ might thus be paraphrased as ‘God’s promised reign is beginning’ or ‘God is now taking control’. (R T France, NICNT, p 102)

This is at every point connected to the fulfilment of hope from the OT, but it cannot be detached from the language of apocalyptic eschatology. The reason that God’s reign needs to come is because all is not right with the world as it is, and because it is dominated by other kingdoms which oppose God’s own will and rule.

The Lord will become king over all the earth; no that day the Lord will be one and his name one (Zech 14.9)

Jewish longing for this coming kingdom is expressed in the closing words of the Kaddish prayer from the time of Jesus:

May God let his kingship rule in your lifetime and in your days and in the whole lifetime of the house of Israel, speedily and soon.

What is remarkable here is John’s claim that the reign of God is coming in the ministry of the One who follows him, that is, in the person and the ministry of Jesus. This extraordinary Christological claim is reinforced by Matthew’s citation from Is 40.3. There, the messenger is preparing the way for God himself—yet John is preparing the way for Jesus, who is now to be addressed as ‘Lord’ in the way that Isaiah calls God ‘Lord’. In the coming of Jesus we see the coming of God to his people Israel.

John’s ministry is taking place on the east bank of the Jordan, north of the Dead Sea (see John 1.28), and only 20 miles from Jerusalem, so it is easy for the crowds to come to him. Josephus tells us that the crowds were so great that Herod Antipas, rule of Galilee and Perea, thought there was a real risk of an uprising (Ant 18.118). Where Luke notes that John rebukes the ‘multitudes’ who come to him, Matthew, with his Jewish focus, identifies those rebuked as ‘Sadducees and Pharisees’, two quite distinct groups who, between them, represent the establishment powers in Jerusalem.

Two questions are raised by John’s preaching and anticipation of Jesus’ ministry.

The first is whether John is the last in the line of OT prophets, and Jesus is by contrast the beginning of the new thing God is doing—or whether John’s and Jesus’ ministry have more in common with one another. It is common in Christian reading of the gospels to assume the former, but Matthew is keen to hold the two together, not least in attributing to John exactly same summary message as he will soon attribute to Jesus in his declaration of the arrival of the kingdom of heaven.

In fact, John and Jesus’ ministry have many things in common.

- The language of ‘brood of vipers’ in Matt 12.34 and 23.33

- The call to repentance in Matt 11.20–21, 12.41

- The importance of producing fruit in Matt 7.16–20 and elsewhere

- The debate about the children of Abraham in Matt 8.11–12

- The fruitless tree being cut down and burned in Matt 7.19

- Judgement by fire in Matt 5.22, 13.40–42, 50, 18.8–9 and 25.41

- The grain being gathered in Matt 13.30

Jesus in Matthew sounds very much like John the Baptist! The image of the grain harvest is also found in Rev 14.14–16, gathered by ‘one like a son of man’.

The second question is whether John is right in associating Jesus’ ministry with judgement. John’s anticipation of Jesus’ ministry:

“I baptize you with water for repentance. But after me comes one who is more powerful than I, whose sandals I am not worthy to carry. He will baptize you with (or ‘in’) the Holy Spirit and fire. His winnowing fork is in his hand, and he will clear his threshing floor, gathering his wheat into the barn and burning up the chaff with unquenchable fire.” (Matt 3.11–12)

There are several significant images of eschatological judgement here. First, the promise of the Holy Spirit being poured out (‘baptism’ means being immersed in or overwhelmed by) is connect with ‘the last days’ in Joel 2.28. Although we might naturally associate ‘fire’ with the tongues of flame at Pentecost in Acts 2, but in fact it is an image of judgement, as the phrase ‘unquenchable fire’ makes clear. (Two interesting things to note here. First, the Greek term for ‘unquenchable’ is asbestos from which we get, well, asbestos! Second, fire is primarily an image of destruction, not torment.) John seems to expect Jesus to be one who will bring the judgement of God to his people and to the wider world.

In Luke’s gospel, there is a sense that judgment is postponed until the end of Jesus’ ministry, with an intervening period of grace creating an opportunity to respond. Matthew is less reluctant to record the language of judgement in the teaching of Jesus, and this is particularly noticeable in Jesus’ six-fold use of the phrase ‘weeping and gnashing of teeth’ in Matt 8.12, 13.42, 13.50, 22.13, 24.51 and 25.30.

The coming of the kingdom of heaven means the coming of the longed-for presence of God with his people. But that will also mean a challenge to the reigning powers of this world, and the personal challenge to us: to whom do you owe your allegiance? Will you respond to the urge call to welcome what God is now doing, and change your ways and your priorities? And this challenge comes most sharply in the ministry of Jesus himself, who will one day return as judge and king over all the earth.

John is right about judgement and Jesus, with two important qualifications. The first is that this judgement is postponed—in the case of Israel until the destruction of the temple in 70AD, and in case of all humanity until the return of Jesus as judge at the end of the age. And the second qualification is that the basis of judgement shifts; for John it is avoided by repentance, baptism and the fruit of that change in tangible change of life. In Jesus’ teaching this is taken up into the question of decision about following him: judgement is no longer on the basis of being part of the ethnic Jewish people of God; nor on the basis of whether we change and begin to obey God’s just commandments; but it is now on the basis of being incorporated into the renewed people of God by accepting Jesus as Lord, and living a new life of holiness empowered by the Spirit. And all this is possible only because of Jesus’ atoning death and resurrection for us.

For video discussion of the issues here, join James and Ian here:

Thanks Ian for a full summary of John and themes of judgement. I think Isa 40 is a key text in John’s relationship to Jesus. He comes though the desert as a forerunner to ensure everyone is ready for the arrival of the king. The smoothing of roads I take to be the removing of unbelief in Israel.

The distinction between John and Jesus and their disciples is instructive too. In Christ the bridegroom has arrived. The law and the prophets were until John. In Jesus the kingdom has arrived. He comes eating and drinking. He that is least in the kingdom is greater than John.

I wish you could see the place of eternal torment. I don’t say that with any relish but simply because it seems to me unavoidable. John’s picture in revelation albeit an image is hard to counter.

If anyone worships the beast and its image and receives a mark on his forehead or on his hand, 10 he also will drink the wine of God’s wrath, poured full strength into the cup of his anger, and he will be tormented with fire and sulfur in the presence of the holy angels and in the presence of the Lamb. 11 And the smoke of their torment goes up forever and ever, and they have no rest, day or night, these worshipers of the beast and its image, and whoever receives the mark of its name.”

I take it the presence of the Lamb and angels is to do with the presence of the judge and his servants as witnesses of the sentence carried out. It won’t do to say it is only the smoke of their torment that lasts forever. This is special pleading especially since he goes on to say they have no rest day or night.

Anyway, that’s as may. Thank you for a stimulating post,

PS

I agree the axe at the root of the tree points to AD 70. I wonder what you make of Zechariah 12-14. Read at face value Jerusalem seems embroiled in an end time battle. Unlike AD 70 this battle is won as the Lord comes to the rescue of his people. In many ways this fits with Dan 7. The Lord has returned to the Mt of Olives.

I know there are probably metaphors at work. Yet much appears historical. I read Webb some time ago and I remember thinking that once you discount the historical it is very hard to create a reasonable analogy or typological fulfilment.

Anyway… this is off the topic… stimulated by your comment on AD 70.

Had another look at Webb. I think I was doing him an injustice.