I have just edited my chapter for a forthcoming volume from Lion Hudson on reconciliation, due out in the Autumn. The first part explores the language of reconciliation in Paul, and its importance in his theology. The middle section looks at reconciliation in Jesus and the gospels. The final section draws out the relevance for contemporary discussion. The issue is highly pertinent in our current context. This is an extract from the section on Paul, where I have already explored the term in Romans 5 and 2 Corinthians 5.

I have just edited my chapter for a forthcoming volume from Lion Hudson on reconciliation, due out in the Autumn. The first part explores the language of reconciliation in Paul, and its importance in his theology. The middle section looks at reconciliation in Jesus and the gospels. The final section draws out the relevance for contemporary discussion. The issue is highly pertinent in our current context. This is an extract from the section on Paul, where I have already explored the term in Romans 5 and 2 Corinthians 5.

Ephesians and Colossians: reconciliation as the goal of the cosmos

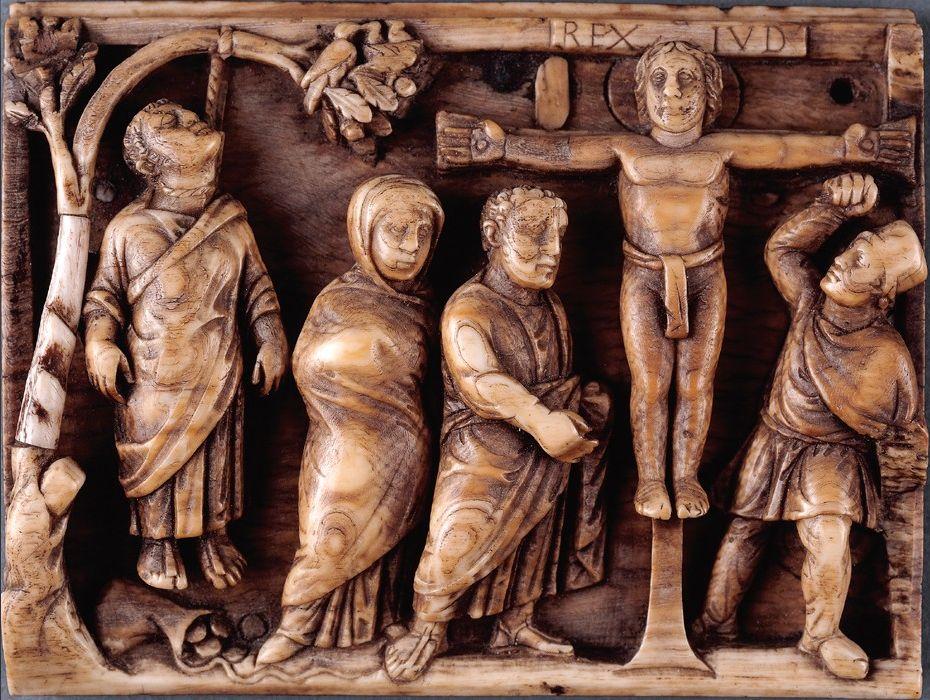

Ephesians 2.14-18: ‘For he himself is our peace, who has made the two one and has destroyed the barrier, the dividing wall of hostility, by setting aside in his flesh the law with its commands and regulations. His purpose was to create in himself one new humanity out of the two, thus making peace, and in one body to reconcile both of them to God through the cross, by which he put to death their hostility. He came and preached peace to you who were far away and peace to those who were near. For through him we both have access to the Father by one Spirit.’

Colossians 1.19-21: ‘For God was pleased to have all his fullness dwell in him, and through him to reconcile to himself all things, whether things on earth or things in heaven, by making peace through his blood, shed on the cross. Once you were alienated from God and were enemies in your minds because off your evil behaviour. But now he has reconciled you by Christ’s physical body through death to present you holy in his sight, without blemish and free from accusation.’

These texts offer a further perspective on the features of the earlier texts above. Like Romans 5, Ephesians 2 emphasises peace with God as the result of reconciliation, which brings us into relationship with God despite our previous situation. Again, reconciliation is in the first instance reconciliation ‘to God’, and only secondarily (though indispensably) between the two groups, Jews and Gentiles. Since the reconciliation is to God, the ‘hostility’ (echthra v 16) which was ‘put to death’ on the cross, must be the hostility of both groups to God.[1] And yet the ‘dividing wall of hostility’ (v 16) is Paul’s reference to the partition wall separating Jews and Gentiles in the Jerusalem temple as a metaphor for the function of the law (Torah) which kept them apart. So it is clear that, with the ending of hostilities towards God, hostilities between these two groups also come to an end.

The importance of reconciliation between these two parties is very striking here. Paul goes so far as to say that the ‘goal’ of God’s plan of redemption was to create ‘one new humanity, making peace.’ He is quite clear that this cannot happen without reconciliation to God, but is also clear that the peace and reconciliation between God’s people is an inevitable consequence. If we are not reconciled with one another, we cannot have been reconciled to God.

This could be seen to function as a summary statement for what Paul says in other ways elsewhere. In his criticism of the Corinthian ‘party spirit’, Paul’s first challenge is ‘Has Christ been divided?’ (1 Cor 1.13). There should be no divisions, but unity, since we are one body in Christ. This is connected to the unity of God in both 1 Corinthians and in Ephesians; there is ‘one God…and one Lord’ (1 Cor 8.6), there is ‘one body, one Spirit…one hope…one Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God’ (Eph 4.3–4).

In the one Spirit we were all baptized into one body—Jews or Greeks, slaves or free—and we were all made to drink of one Spirit. (1 Cor 12.13)

Reconciliation between people cannot happen without reconciliation with God, who in the cross has destroyed the things that cause enmity both with God and between people. But reconciliation with God cannot help but lead to reconciliation between people, since God ‘is a God of peace’ (1 Cor 14.33). In that sense, reconciliation and peace amongst God’s people is testimony to reconciliation with God in Christ.

The similar text in Colossians also mentions peace, and is slightly closer to Romans 5 in talking of us as ‘enemies’ rather than referring to ‘enmity’. The perspective here is not on the Jew/Gentile relationship, but on the cosmic vision of the reconciliation/restoration of all things. The focus here is more exclusively ‘upward’, in that Paul talks of reconciliation to God effecting holiness (more clearly than in any part of Romans), without mentioning explicitly the consequences for relations between Christians. There is perhaps an echo of Romans 8.1 (‘no condemnation’) in the idea of being ‘free from accusation’ and some connection with Revelation 12.10 (‘the accuser … is thrown down’) though in neither case is there a clear verbal link.

Reconciliation within Paul’s Theology

All this presents us with a puzzle. The occurrences of the term ‘reconciliation’ are relatively few in Paul’s letters, but they appear to have great significance within the shape of Paul’s theology. How do we make sense of this? Ralph Martin proposes five criteria for discerning the centre of Paul’s theology:

- the primacy of God’s grace;

- the cosmic significance of what God has done in Christ;

- the centrality of the cross (and, we might add, resurrection);

- ethical imperative – the move from the indicative to the imperative, from what God has done in Christ to how Christians should then live;

- the missionary mandate.

Reconciliation, more than any other term, meets these criteria for being the centre of Paul’s theology. Martin writes:

It is the overall theme of reconciliation … that meets most – if not all – these tests. This is not to say that the word-group katallass- is prominent in Paul’s writings; manifestly it is not … But the contention stands, namely, that reconciliation provides a suitable umbrella under which the main features of Paul’s kerygma and its practical outworking may be set.[2]

If this is the case, it is then less surprising that Tom Wright should introduce his magnum opus on Paul’s theology with a study of his letter to Philemon, which has not traditionally been put at the centre of Paul’s thinking. But Wright justifies this in very similar terms to Martin. Although Paul values freedom, he values the mutual reconciliation of those who ‘belong to the Messiah’ as more important—indeed, as taking precedence over all other concerns. ‘Reconciliation is what mattered.’[3]

If this is the case, it is then less surprising that Tom Wright should introduce his magnum opus on Paul’s theology with a study of his letter to Philemon, which has not traditionally been put at the centre of Paul’s thinking. But Wright justifies this in very similar terms to Martin. Although Paul values freedom, he values the mutual reconciliation of those who ‘belong to the Messiah’ as more important—indeed, as taking precedence over all other concerns. ‘Reconciliation is what mattered.’[3]

The heart of it all…is koinonia, a ‘partnership’ or ‘fellowship’ which is not static but which enables the community of those who believe to grow together into a unity across the traditional divisions of the human race. This is a unity which is nothing other than the unity of Jesus Christ and his people, – the unity, indeed, which Jesus Christ has won for his people precisely by his identifying with them and so, through his death and resurrection, effecting reconciliation between them and God.[4]

Wright goes on to describe Paul’s understanding of reconciliation and the unity of those in Christ as an anticipation of the goal of all humanity as springing out of a Jewish world view, but then creating a new worldview all of its own.[5]

If reconciliation is of central importance in understanding what God has done, we might then expect peace (the result of reconciliation) to have similar importance. It is striking that in all his letters, Paul modifies the tradition greeting from ‘grace’ to ‘grace and peace.’ Michael Gorman thinks this is no accident:

For Paul, the prophetically promised age of eschatological, messianic peace has arrived in the death and resurrection of Jesus the Messiah, an age characterized especially by reconciliation and nonviolence.[6]

Alan Spence, in his fascinating study of the atonement in Paul, also puts peace at the centre of Paul’s theology:

[I] offer a provisional, highly condensed answer to the question: Why did God become man? It takes the shape of a master-story, presenting in narrative form the concept that Jesus is Mediator: The Son became as we are so that he might, on our behalf, make peace with God. This is more than an account individual forgiveness. It summarises God’s gracious intention to reorder and reconstitute around himself the broken relationships of his suffering and alienated creation through the death of his Son and by the work of his Spirit.

[1] It might be objected that the Jews, as God’s chosen people, were hardly ‘hostile’ to God. And yet, in line with his argument in Romans 2, Paul describes Jews (‘we’) as ‘children of wrath’ as much as Gentiles (Ephesians 2.3).

[2] R.P. Martin, ‘Center of Paul’s Theology’, in Hawthorne, Martin and Reid, Dictionary of Paul and His Letters, pp. 93-94. For a fuller defence of this, see R.P. Martin, Reconciliation: A Study of Paul’s Theology (Zondervan, 1989).

[3] N.T. Wright, Paul and the Faithfulness of God (SPCK, 2013), p. 12.

[4] Ibid, p. 16.

[5] Ibid, p. 30.

[6] Michael Gorman Peace in Paul and Luke (Grove, 2015), p. 8

Much of my work is done on a freelance basis. If you have valued this post, would you consider donating £1.20 a month to support the production of this blog?

Applying this interesting post to today’s situation, how do Christians reconcile with one another when each side’s convinced that God’s saying different things?

May I respond to this comment 5 years late, James. I hope Ian would not mind and would love to hear what Ian thinks as well given his thesis in Paul Ricoeur. I think the answer is in post-modernism and a hermeneutic of faith that allows us to say ‘I really don’t know, and might never know in this age, let God be the judge’ — instead of imposing a rational doctrine onto a text that is at times indeterminate (at least to us humans) on matters touching contemporary life.

But Ricoeur’s ‘hermeneutic of faith’ involves actual making a decision about what things actually mean. This is precisely what requires faith!